LAWMAKING

Countering Extremism and Terrorism

Increasing the Severity of Related Legislation

Regulating the Internet

“Foreign Agents” and “Undesirable Organizations”

LAW ENFORCEMENT

Regulation of Public Speech

Article 2052 CC on Propaganda of Terrorism

Article 280 CC on Calls for Extremist Activity

Article 2804 CC on Calls for Actions That

Threaten State Security

Article 2824 CC on Displaying Prohibited

Symbols

Article 2073 CC on the Dissemination of

Fakes about the Activities of Armed Forces and Government Agencies

Article 2803 CC on Discrediting Armed

Forces and Government Agencies

Article 282 CC on Incitement to Hatred

Article 3541 CC on “Rehabilitation of

Nazism”

Article 148 CC on Insulting the Religious Feelings of

Believers

Vandalism

Summary Data for Articles on Public Speech

Regulation of Organized Activities

Nationalist Associations

“Citizens of the USSR”

Banned Ukrainian Organizations

Banned Opposition Organizations

Banned Religious Organizations

Jehovah’s Witnesses

Followers of Said Nursi

«Tablighi Jamaat»

«Hizb ut-Tahrir»

«Allya-Ayat»

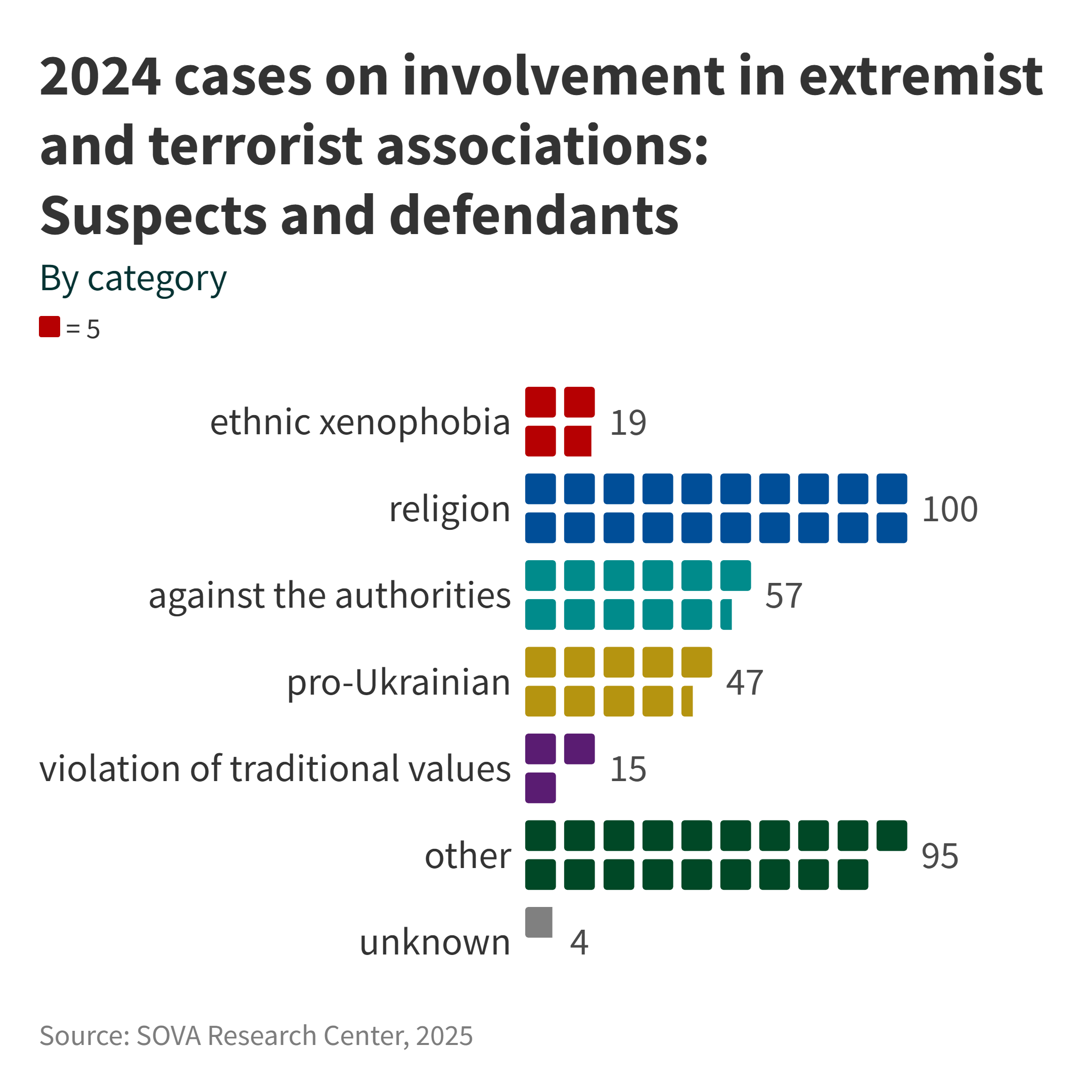

Summary Data on Cases of Involvement in Banned

Religious Organizations

Associations Deemed Contrary to “Traditional Values”:

LGBT

Other Banned Associations: AUE

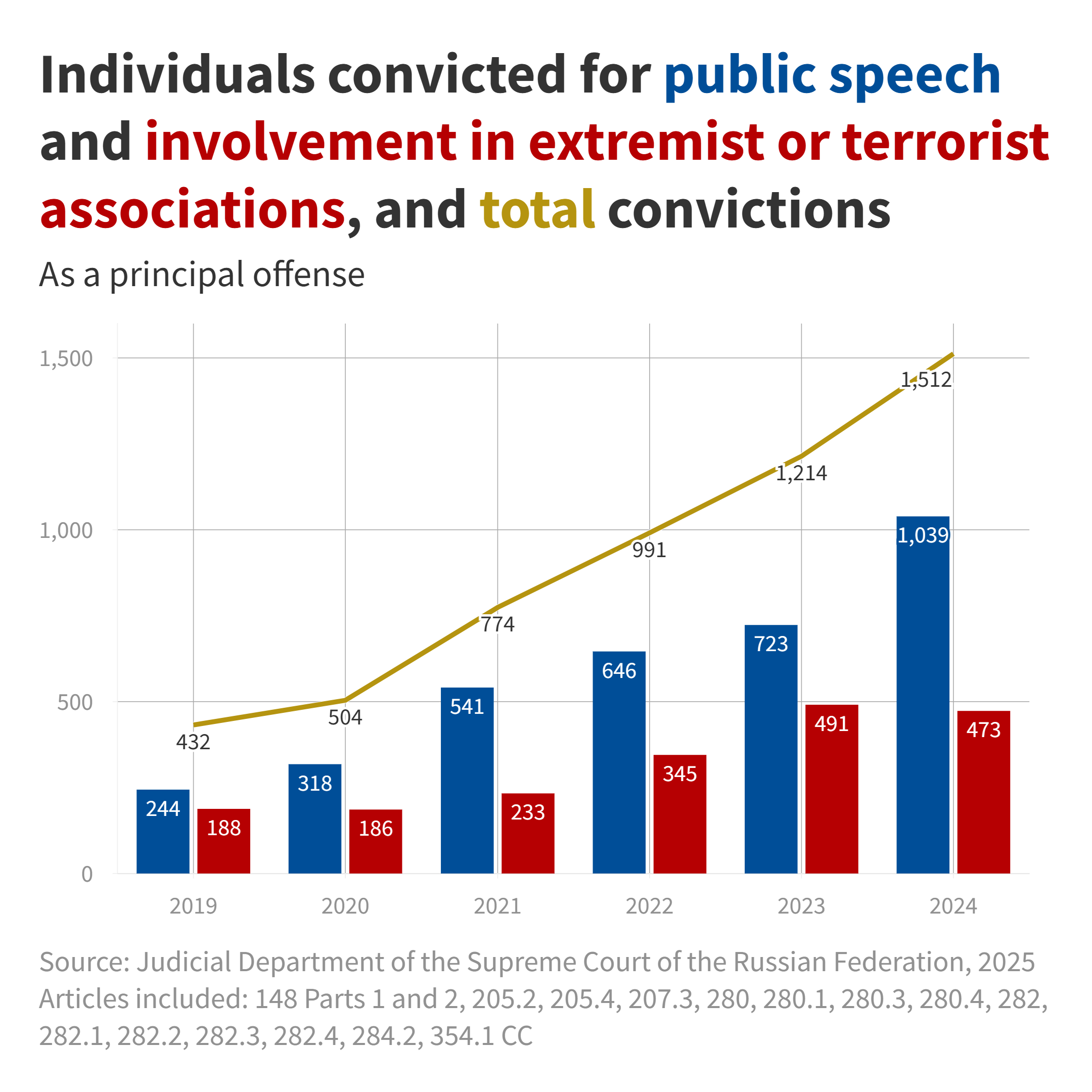

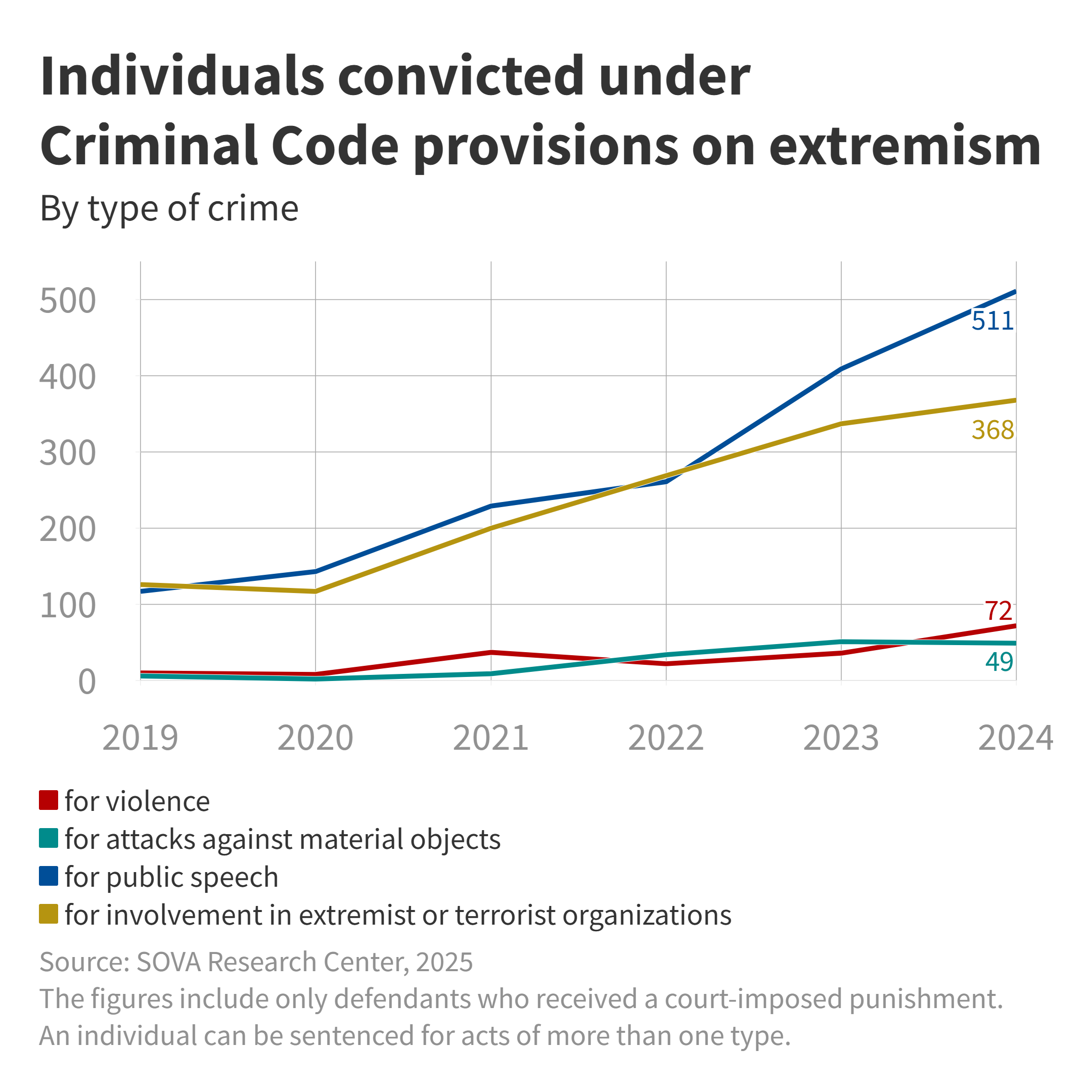

Overview of Convictions under

Articles on Participation in Prohibited Organizations

Federal List of Extremist Materials

Recognizing Organizations as Extremist or Terrorist

SUMMARY

STATISTICAL SUMMARY ON CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS

This report is an analytical review of anti-extremist legislation and its use in 2024 to regulate public speech and organized activities. SOVA Center has been publishing such reports annually, summarizing the results of monitoring carried out continuously since the mid-2000s. We define anti-extremist policy as the criminalization of actions driven by political or ideological beliefs in a broad sense. Our analysis extends beyond the formal framework, since we also monitor restrictions related to acts not classified as “extremist crimes” in the law “On Countering Extremist Activity.”

Unlike in previous years, we have decided to merge the review into one, addressing law enforcement in general and related abuses together.[*]

Drawing on our monitoring data and official statistics, we present an analysis of law enforcement across several parameters, including its ideological and political focus, types of penalty, and the appropriateness of prosecutions.

Lawmaking

In 2024, Russian legislation on countering extremism saw no significant changes – only a few procedural amendments were introduced. However, a new Strategy for Countering Extremism approved late in the year, laid the groundwork for further developments. Notable innovations occurred in a related area: Internet regulation, particularly concerning provisions on “foreign agents” and “undesirable organizations.”

Countering Extremism and Terrorism

A law signed in March identified the articles of the Criminal Code (CC) for which a sentence could not be replaced by participation in the special military operation. In October, a similar eligibility exception was introduced for individuals under investigation under the same articles. As expected, the list included members of extremist and terrorist organizations and groups. On the other hand, individuals convicted of (or charged with) vandalism, hooliganism and hate-motivated violent crimes or under Article 2056 (failure to report a terrorist crime), Article 282 (incitement to hatred), Article 2803 (repeated discrediting of the activities of the army and officials abroad), Article 2073 (dissemination of false information about the activities of the Russian military and officials abroad) and Article 3541 (“rehabilitation of Nazism”) CC are allowed to join the special military operation.

In late December, the list of criminal offenses that result in individuals being added to the Rosfinmonitoring register – whether convicted, charged, or merely suspected – was expanded. The newly included articles relate to terrorism and extremism but had not been part of the list previously for various reasons: Article 357 (genocide) CC, Article 2802 (violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation), and Articles 2803 and 2824 (repeated display of prohibited symbols) CC. Also included are individual paragraphs of the articles on calls for activities against state security (paragraph “e” of Article 2804 Parts 2 and 3), “military fakes” (paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Parts 2 and 3), hooliganism (paragraph “b” of Article 213 Parts 1, 2 and 3), vandalizing burial grounds (paragraph “b” of Article 244 Part 2) and certain articles on violent crimes[1] specifying the hate motive. Other articles of the CC also qualify if the crimes falling under them involve a hate motive (paragraph “f” of Article 63 Part 1 CC). Crimes falling under two of the articles mentioned above, specifically Articles 2803 and 357 CC, are not currently categorized as extremist or terrorist[2] However, this discrepancy is likely to be resolved in the future, and these articles will be included in the relevant lists of norms.

We would like to point out two additional changes that could be characterized as procedural and generally positive.

The law signed in February required that cases related to recognizing materials as extremist be reviewed in courts of federal subjects, rather than in district courts as before. Such a measure, intended to improve the quality of legal proceedings, was proposed to the State Duma back in 2015. At the same time, authors, translators, or publishers of materials, if known, should be involved in the trials – not as defendants, but as interested parties, so that the process of banning the material does not automatically lead to charges against them; they pay no legal costs. If the material in question is religious, the process must involve an expert “with specific knowledge of the relevant religion.” While this expansion of trial participants is not a cure-all for unreasonable or inappropriate bans, it can help reduce formalism in the consideration of such cases.

In late December, the president approved a law that stipulated the process of removing an entity from the list of terrorist organizations, at least temporarily. This is to be done by a court at the request of the Prosecutor General's Office, if the latter believes that the organization has ceased terrorist activity. The bill was adopted to normalize relations with the Taliban government of Afghanistan (and on April 17, 2025, the Supreme Court suspended the ban against the Taliban). Regardless of our views on the Taliban, such a legal procedure is indeed necessary – not only for terrorist organizations, but also for extremist ones.

In 2024, legislators failed to address a clear shortcoming in the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO) regarding the calculation of the administrative liability period. Under Article 4.5, for most offenses, this period is calculated not from the moment the offense was committed, but from when it was detected, resulting in numerous punishments under the CAO for online statements made many years earlier.

In March, the Constitutional Court refused to consider Yelena Selkova's complaint against her punishment under Article 20.3 CAO for symbols viewed as attributes of a banned organization (the Navalny Headquarters), even though she had published them before the organization was recognized as extremist. The Constitutional Court directly stated that Selkova’s actions became an offense at the moment the organization was banned.

In April, the State Duma rejected a bill by Vladislav Davankov from the New People (Novye Lyudi) faction, which proposed calculating the liability period under the CAO for Internet offenses (with some exceptions) from the moment the offense was committed.

In October, a bill was introduced in the State Duma proposing to extend the territorial scope of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation to cover the entire world – similar to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, which already applies to offenses committed abroad that are deemed to be “against the interests of the Russian Federation.” This is the second such bill submitted by the State Council of Tatarstan. However, there is still no consensus on which specific CAO articles would be involved. In May 2025, the Duma passed the bill in its first reading, but without clarifying the relevant articles, leaving the issue unresolved. Of course, emigrants already face liability under several CAO provisions, as reports of acts committed outside Russia are often filed at the location where the offense was detected. Nevertheless, the new bill appears aimed at increasing pressure on them.

In late December, the President signed a decree on the new Strategy for Countering Extremism,[3] the provisions of which suggested potential future expansions of the legislation.

The definition of “manifestations of extremism” was expanded to include “the motive of hatred or hostility towards representatives of public authorities”; previously, it was treated as hatred or hostility based on membership in a social group. The list of key concepts was expanded to include “xenophobia” and “Russophobia.” The first term was given a generally accepted definition, the second was described as hostility towards Russian citizens, the Russian language, culture, traditions, and history of Russia, expressed “also through aggressive sentiments and actions of political forces and their individual representatives, as well as discriminatory actions of the authorities of unfriendly states against Russia.”

In general, the Strategy, as expected, devotes a lot of attention to describing hostile activities of “unfriendly” states. In particular, it states that “unfriendly states use the Ukrainian crisis to unleash hybrid wars” against Russia and “incite aggressive Russophobic sentiments in the world.” To counter these phenomena, the Strategy provides for “improving the mechanisms for countering the illegal and anti-Russian activities of foreign or international non-governmental organizations, including those recognized as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation,” measures aimed at “preventing and countering the spread of extremism, neo-Nazism and Ukrainian nationalism,” “creating a database of individuals who have left the Russian Federation to participate in extremist organizations or to undergo training in foreign centers of unfriendly states,” identifying and suppressing the instigation of “color revolutions,” and monitoring interethnic and territorial conflicts that can “lead to manifestations of separatism in the relevant territories.”

The document elaborates more extensively than the previous strategies on the adverse effects of the “unfavorable situation in certain subjects of the Federation and settlements,” attributed to the “illegal activities of migrants,” on interethnic and interreligious relations. Accordingly, it expands the list of state migration policy measures to introduce stricter rules for foreigners' stay in Russia as well as social and cultural adaptation programs for them.

The Strategy also outlines specific cultural initiatives, including efforts to “counter the propaganda of fascist and neo-Nazi ideas,” support creative projects that promote “the strengthening of an all-Russian civic identity,” and assist in the creation of works of art aimed at preventing citizens from being drawn into the activities of “destructive organizations.” The directives related to working with young people follow a similar focus.

Increasing the Severity of Related Legislation

In February, two new qualifying features – committing a crime motivated by hatred (clause “e”) and for mercenary motives (clause “d”) – were added to Article 2804 Part 2 CC, which is not yet frequently used.

These amendments also expanded the list of offenses that allow for the confiscation of property. In particular, they introduced the possibility of confiscating property obtained as a result of committing crimes under Articles 2073 and 2804 CC when committed for mercenary reasons. In April 2025, Articles 2803, 2842 (calls for sanctions), and 2843 (assistance to foreign criminal prosecution of Russian officials and military personnel) were also added to this list.

Meanwhile, the possibility of confiscating property used to commit a crime was stipulated for cases related to financing extremist and terrorist activities, or activities against the security of the Russian Federation. The latter was clarified in the amendments with a long list of specific crimes, including treason, sabotage, Article 2841 (participation in the activities of an “undesirable organization”), and 2843 CC, as well as ordinary criminal offenses, such as participation in organized crime.

The confiscation rules introduced by the amendments are either primarily declarative (intended to intimidate citizens) or aimed at seizing certain business assets. After all, computers could already be confiscated as instruments of crime under existing laws, and a person’s only residence is not subject to confiscation.

At the same time, the law introduced the possibility of stripping individuals of ranks, titles, and awards as a penalty under eleven articles of the CC, but this change can hardly be considered significant.

In late December, a law was signed to amend several articles of the CC pertaining to rebellion and various forms of treason.

Article 279 CC on armed rebellion was divided into three parts. The previous penalty – from 12 to 20 years of imprisonment – was included in Part 2 and remained in force for ordinary participants. Part 1 was introduced for the organizers of the rebellion, with the associated prison terms ranging from 15 to 20 years. If the rebellion results in someone’s death or other serious consequences, Part 3 provides for prison terms ranging from 15 years to life for its organizers and participants.

The scope of Article 2751 CC (cooperation on a confidential basis with a foreign state, international or foreign organization) has been expanded to include foreigners and stateless persons; previously, only Russian citizens could be held liable under this article.

In addition, a new article 2761 (aiding an armed enemy in activities directed against the security of the Russian Federation) was added to the CC. Penalties under this article include imprisonment for a term of 10 to 15 years and a possible fine of up to 500 thousand rubles or wages or other income for a period of up to three years.

A footnote to Article 275 of the Criminal Code defines the term “enemy” to clarify the meaning of “adhering to the enemy,” as penalized under the article.

In 2024, we witnessed yet another attempt to expand the scope of the part of Article 3541 CC that deals with the denial or glorification of Nazi crimes by adding denial or glorification of the “genocide of the Soviet people.” Defendants had previously faced sanctions under Article 3541 CC for such statements, specifically about crimes against Soviet citizen, although the term “genocide” has not been used with respect to the Soviet people as a whole – either by the Nuremberg or subsequent tribunals, or in any other legally authoritative documents. Nevertheless, activists from the Russian Military Historical Society have promoted the concept of the “genocide of the Soviet people” for several years, and it has appeared in several decisions of regional courts.

In February 2024, a group of deputies from “A Just Russia – Patriots – For Truth” (Spravedlivaya Rossiya – Patrioty – Za pravdu, SRZP) submitted a package of bills to the State Duma on the “genocide of the multiethnic Russian people,” which included a special commemorative law and the corresponding amendment to Article 3541 Part 1 CC. The package was quickly returned to its authors to address its shortcomings, but already in June, a new bill was submitted to parliament – this time from representatives of all factions. Its preamble stated that the genocide of the Soviet people had already been established at Nuremberg, thereby justifying “the recognition of the public justification of Nazi ideology and the genocide of the Soviet people as illegal, and the implementation of measures to counter such propaganda.” The law was not adopted immediately, but it quickly passed all readings in the State Duma in April 2025 and was signed by the president later that month. The adoption of such a law implies further amendments to Article 3541 of the Criminal Code, and possibly to other provisions as well, but this has not yet occurred. However, the new law is expected to come into force only at the beginning of 2026.

Regulating the Internet

In August, the president signed a package of laws banning trash streams and imposing liability for them.

The first law introduced a new aggravating circumstance into the CC (paragraph “s” of Article 63 Part 1 CC) – “commission of an intentional crime with its public demonstration, including in the media or information and telecommunications networks (including the Internet).” A similar provision was introduced as a qualifying element for ten types of intentional violent crimes, ranging from murder to the use of slave labor. At the same time, those among the ten articles that previously did not provide for additional sanctions in the form of deprivation of the right to hold certain positions or engage in certain activities now prescribe such penalty for a period of up to three years. This law implemented a principle we view as appropriate: that a public demonstration of violence should be considered an aggravating circumstance in court proceedings related to that violence.

The second law introduced a new Part 12 to Article 13.15 CAO, which resists easy interpretation. It is formulated as follows: “Dissemination via information and telecommunications networks, including the Internet, of information that offends human dignity and public morality, expresses obvious disrespect for society, contains images of presumably illegal actions, including violence, and is motivated by hooliganism, monetary gain, or other base motives, if these actions do not constitute a criminal offense.”

A note has been added to this provision stating that the norm does not apply to “works of science, literature, or art; works of historical, artistic, or cultural value; materials from registered mass media; as well as photo and video materials intended for scientific or medical use, or for study as provided by federal state educational standards and federal educational programs.”

Penalties range from 50 to 100 thousand rubles for individuals, from 100 to 200 thousand for officials, and from 800 thousand to a million rubles for legal entities.

Apparently, the legislator intended to distinguish trash streams and other “amateur activities” involving the display of violence from legitimate displays in media reports, works of art, and similar contexts. However, it remains unclear how this legislation will be implemented in practice. After all, the concept of “other base motives” has seen little use so far, and it is difficult to imagine how the police will evaluate the “historical, artistic, or cultural value” of certain materials. We currently have no data on the application of this new provision.

The third law in the package addresses the blocking of materials if their content falls under Part 12 Article 13.15 CAO; however, the above-mentioned exception is omitted. Responsibility for implementing the blocking has been assigned to online platforms, which must act either on their own initiative or at the request of the Prosecutor General's Office. This creates the potential for significant abuse – or simply errors – in the application of the law.

As part of the same package of laws, Internet censorship mechanisms became even more severe.

First, the Prosecutor General’s Office acquired the legal authority not only to issue blocking orders but also to direct Internet service providers to throttle traffic on specified platforms. Such measures may be applied selectively, for example, within a specific region. Consequently, providers became subject to stricter obligations to install the requisite technical equipment.

Next, while previously decisions on extrajudicial blocking had been based on the illegality of some material, as determined by the Prosecutor General's Office, the same law permitted such blocking in accordance with the "acts of the president".

Finally, another law from the same package revived the idea of a blogger registry that existed from 2014 to 2017. Social media users with an audience of over ten thousand were required to register. Those who failed to do so were prohibited from soliciting advertisements and collecting donations, and other users were barred from sharing their content – although liability for this violation has not yet been established.

“Foreign Agents” and “Undesirable Organizations”

In August, the mechanism for recognizing organizations as “undesirable” was expanded: the amendments allowed to impose this status not only on organizations with private founders but also on those with foreign state founders or participants. However, as far as we know, no organizations added to the relevant register since this mechanism came into force had such founders or participants.

Amendments to the electoral legislation signed in May introduced new restrictions for “foreign agents.” Foreign agents, as well as individuals featured on the Rosfinmonitoring List of persons involved in extremist or terrorist activities, were banned from running for office at all levels. Individuals on both registers were also banned from participating in elections as observers, authorized representatives, or trusted representatives of candidates.

Individuals punished under the CAO articles on prohibited symbols (Article 20.3) and prohibited materials (Article 20.29) were barred not only from running for election for one year, as had previously been the case, but also from serving as voting members of election commissions.

In addition, current deputies and senators were required to resign if designated as “foreign agents.” The amendments gave such deputies 180 days to relinquish either their “foreign agent” status or their mandate. Several deputies actually resigned. Thus, it became possible to cancel the already expressed will of the voters by a simple order of the Ministry of Justice.

Foreign agents, whether legal entities or individuals, were significantly restricted in access to their income. The law signed in late December effectively treats “foreign agents” similarly to citizens of “unfriendly countries.” Income from the sale or lease of housing or vehicles, any fees, and even interest and dividends on deposits and accounts received after March 1, 2025, must be transferred to a special account, which can only be used to pay fines. There is no other access to the account until the “foreign agent” status is lifted.

Although this measure discriminated against all “foreign agents,” the authors of the law made it clear that the primary target was political emigrants.

Another bill, which passed its first reading in June 2024 but has not yet been adopted, also largely targets emigrants, although not exclusively. The draft law proposes authorizing the Russian Ministry of Culture to issue an order establishing a specific procedure for libraries – a procedure not defined in the law itself. This procedure would set rules for “providing and posting documents” created by people and organizations designated as “foreign agents” or included in the Rosfinmonitoring registry. Thus, this provision does not focus on the distribution of individual materials due to their content but rather on creating a “blacklist of authors.”

The same bill provides for the introduction of a special procedure for access to libraries in the DPR, LPR, Zaporizhzhya Region, and Kherson Region, since the library collections there have not been sufficiently cleared of “anti-Russian” literature and other works that the authorities find objectionable.

Law Enforcement

In this section, we present 2024 statistics on the use of criminal articles related to public statements and the activities of prohibited organizations. Please note that our monitoring does not cover law enforcement practices in the territories annexed by Russia between 2022 and 2024.

Regulation of Public Speech

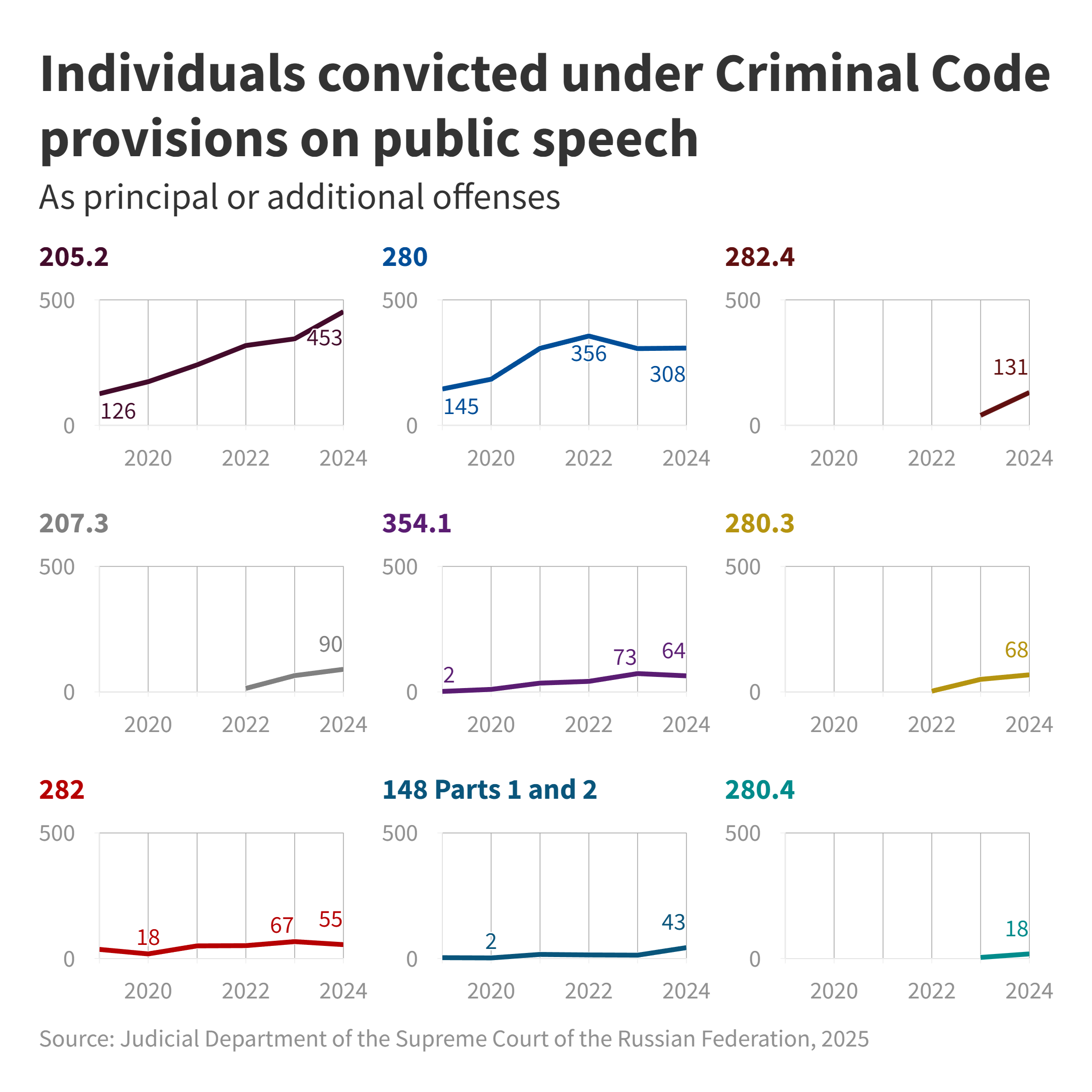

This section, devoted to Criminal Code articles on public statements, analyzes statistical data for each relevant article – starting with the most frequently used and followed by others in descending order based on the number of sentences issued in 2024 – along with similar provisions applied in rare cases.

Thus, we will review the use of the following articles of the CC:

- Article 2052 on calls for terrorist activity or its justification;

- Article 280 on calls for extremist activity[4];

- and the closely related Article 2804 on public calls for activities against state security;

- Article 2824 on repeated display of prohibited symbols;

- Paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 on disseminating “fake news” about the use of armed forces and the actions of government agencies abroad, motivated by hatred;

- Article 2803 on repeated discrediting of the use of armed forces and actions of government agencies abroad;

- Article 282 on incitement to hatred or enmity;

- Article 3541 on the “rehabilitation of Nazism”;

- Article 148 Parts 1 and 2 on publicly insulting the religious feelings of believers.

You can find additional information on the articles that fall within the scope of the SOVA Center’s monitoring and the principles guiding their selection on our website.

First, we will present statistical data from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of Russia on individuals convicted under these articles in 2024, whose sentences came into force in the same year.[5] For each part of each article of the Criminal Code, the Department reports the number of individuals convicted either under it as the principal offence or as an additional charge, with the principal offence defined as the most serious article among the charges. The Department also publishes data on the penalties imposed under all parts of all articles; such information is linked to the main offense, ensuring that the penalty for each convicted individual is counted only once.

SOVA Center collects information on sanctions under articles related to public statements on a daily basis by monitoring Russian court websites, mass media, social networks, and other sources. However, due to the lack of transparency in this area of law enforcement, we can obtain information for only a portion of the sentences issued by Russian courts during the year. In 2024, we had such information for approximately 50 % of the cases.

We include this information in a publicly accessible database on our website. Please note that it contains all sentences we are aware of, not just those that came into force in the same year they were issued.

This report presents the results of our analysis of 2024 sentences available to us, grouped according to various parameters provided in the database.

We will sort the sentences under each article among the following tentative categories, depending on the nature of the public statements that served as the basis for the charges:

- statements characterized by ethnic xenophobia;

- statements related to religion;

- statements critical of the authorities and their supporters;

- statements related to events in Ukraine;

- statements involving “violation of traditional values”;

- other cases, including unattributed ones.

It should be noted that a single sentence may often fall into more than one category. We will highlight instances of significant overlap between categories for each article.

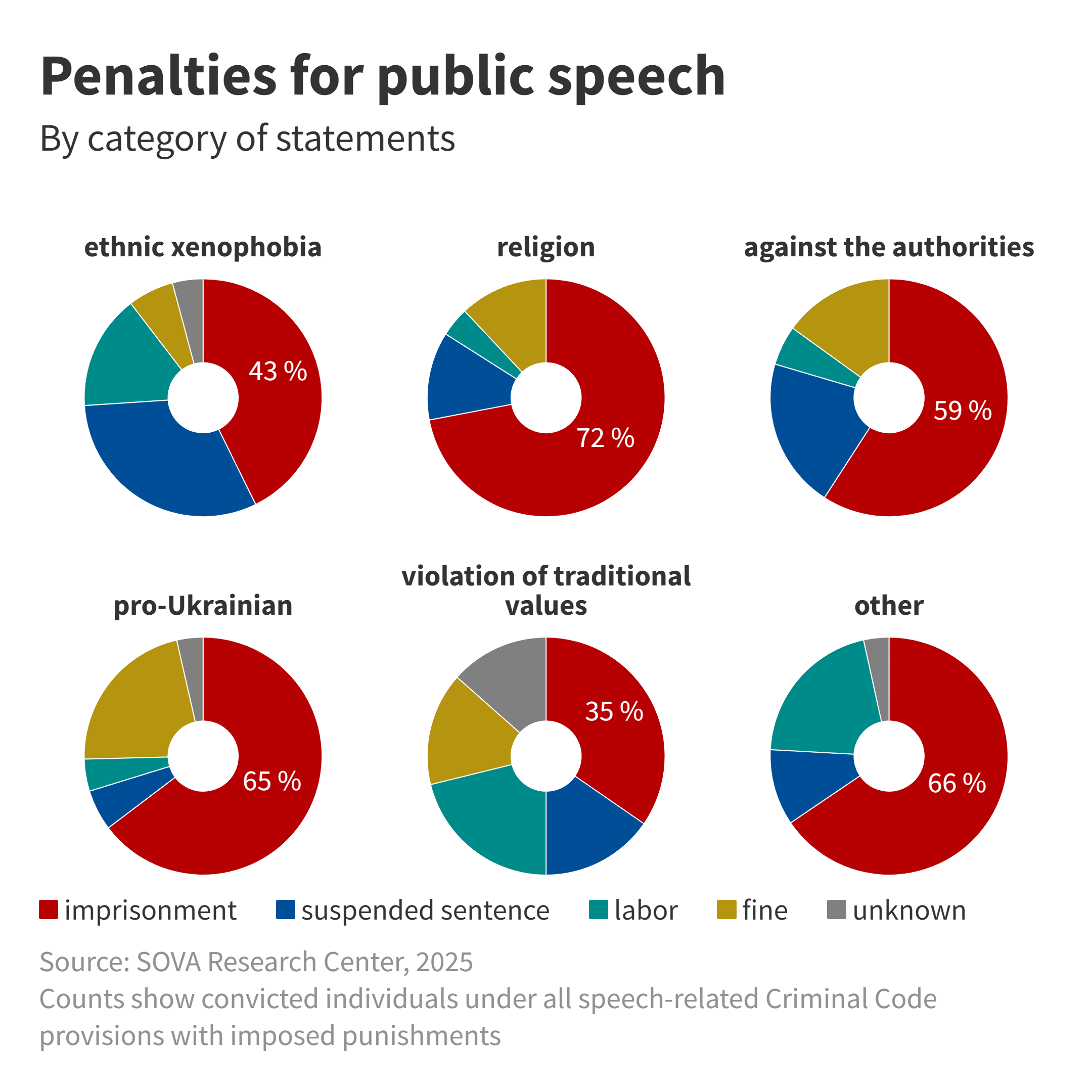

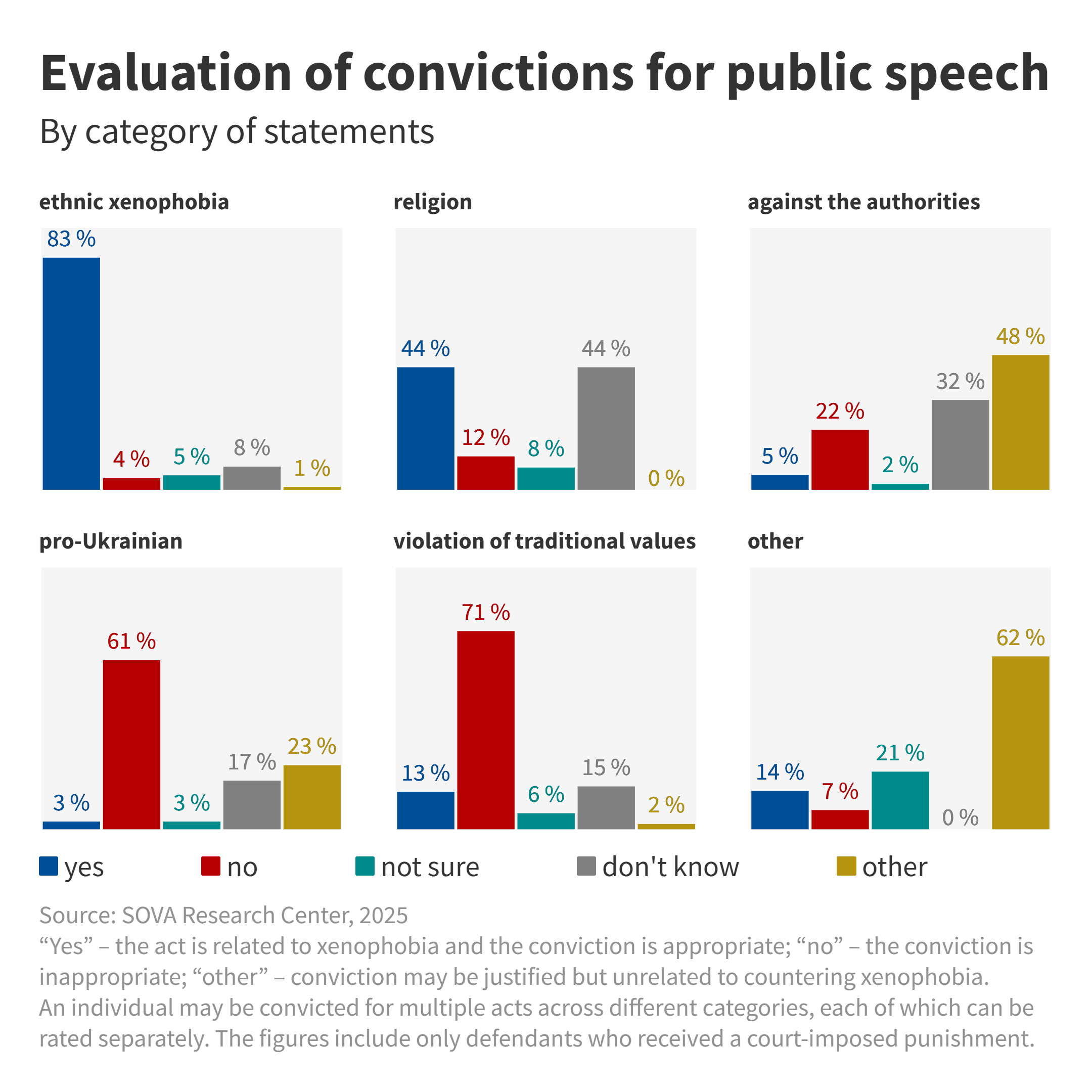

We will show the ratio between the number of people punished for public statements online and offline, as well as the distribution of penalty types within each category and for each article as a whole.

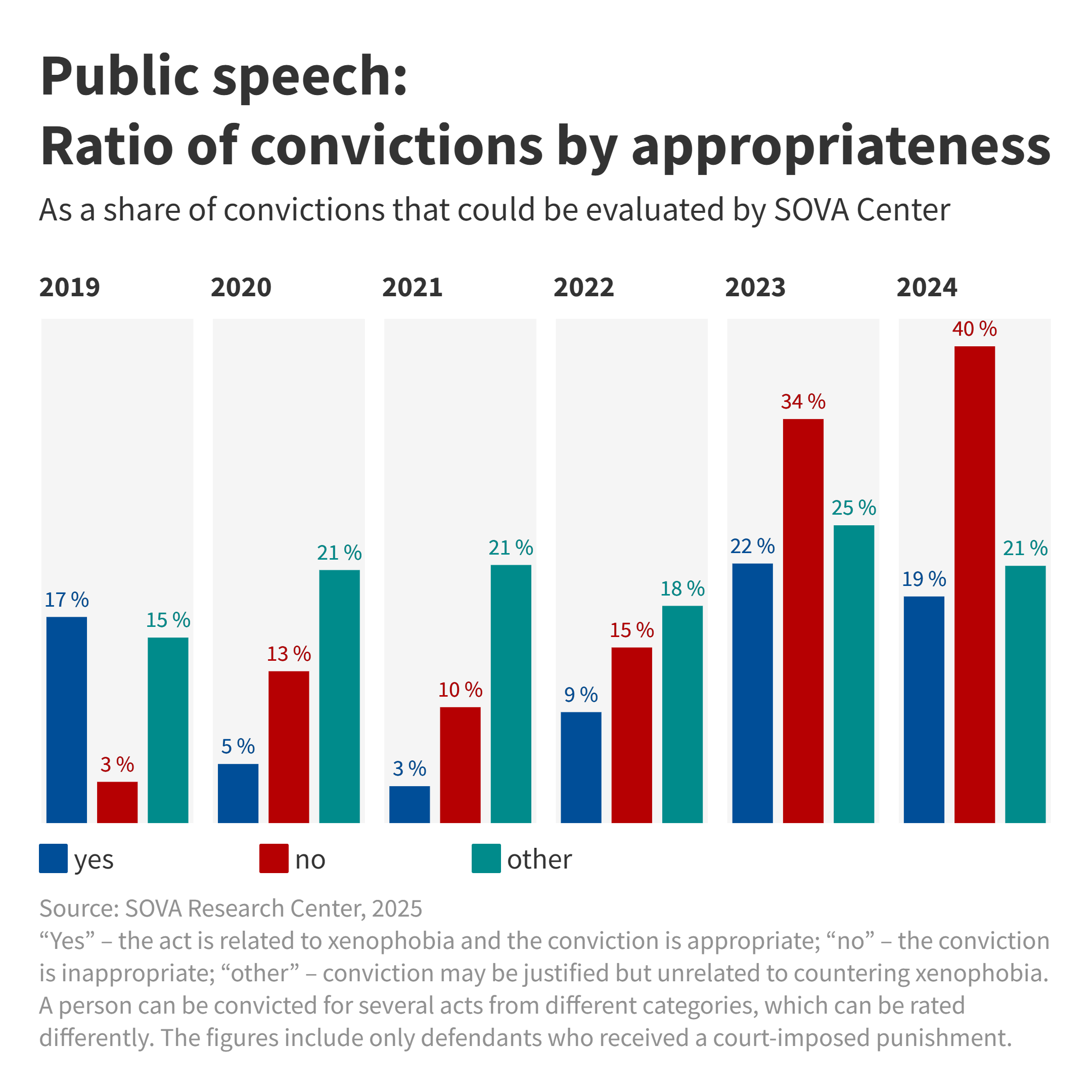

Once we have reviewed information about a particular case and entered it into our database, we assign it a rating based on whether we consider the restriction of freedom of expression in that case to be justified. Our ratings include: “Yes” – if we view the act as related to xenophobia and the restriction as generally justified; “No” – if we believe the restriction violated the right to freedom of expression and was therefore inappropriate; “Other” – if the restriction was justified but unrelated to countering xenophobia; “Not sure” – if we cannot choose between the above values for any reason; and “Don’t know” – if we lack adequate data for making our assessment. This report presents the assessments for the 2024 cases related to the articles of interest.

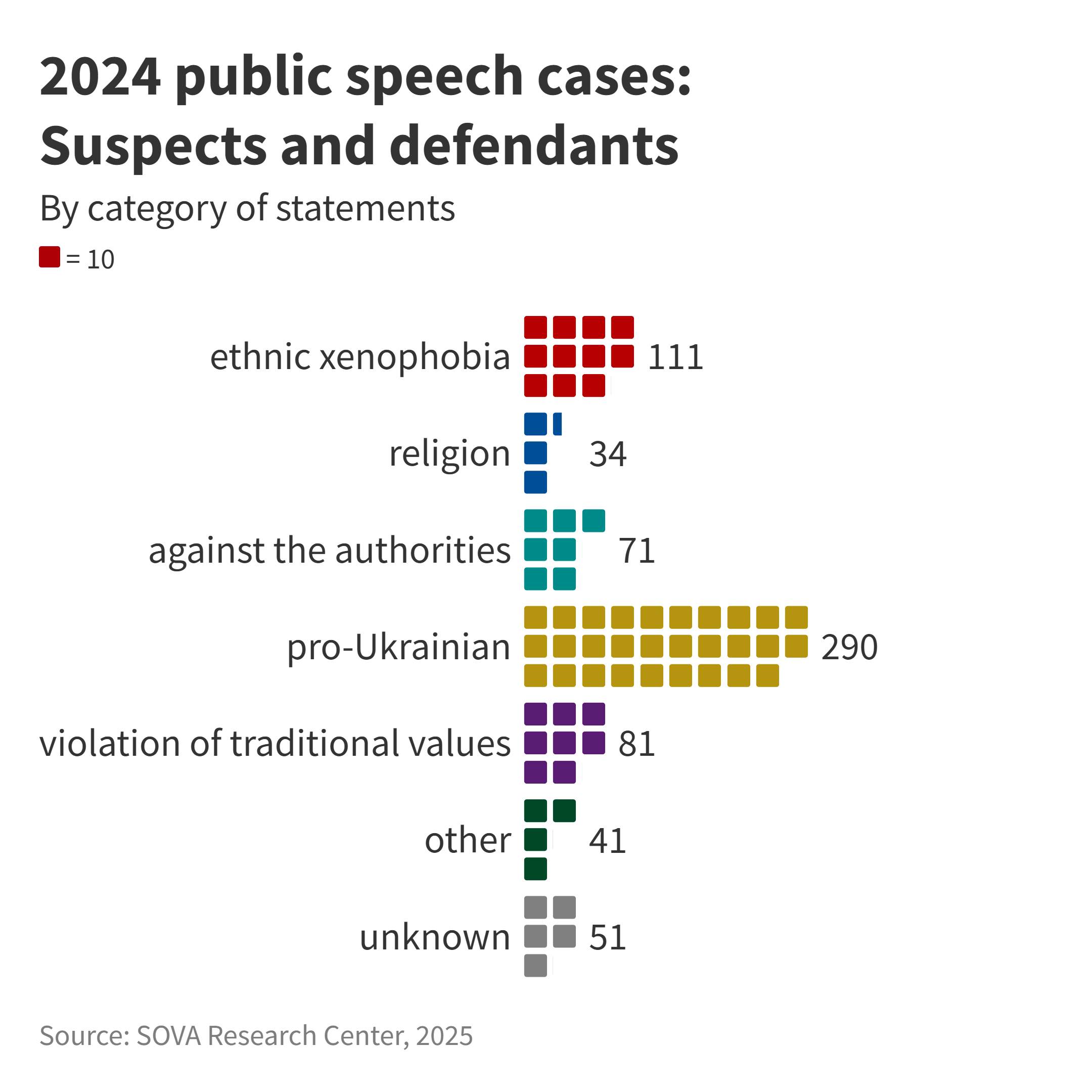

We shall provide similar information about cases initiated in 2024.

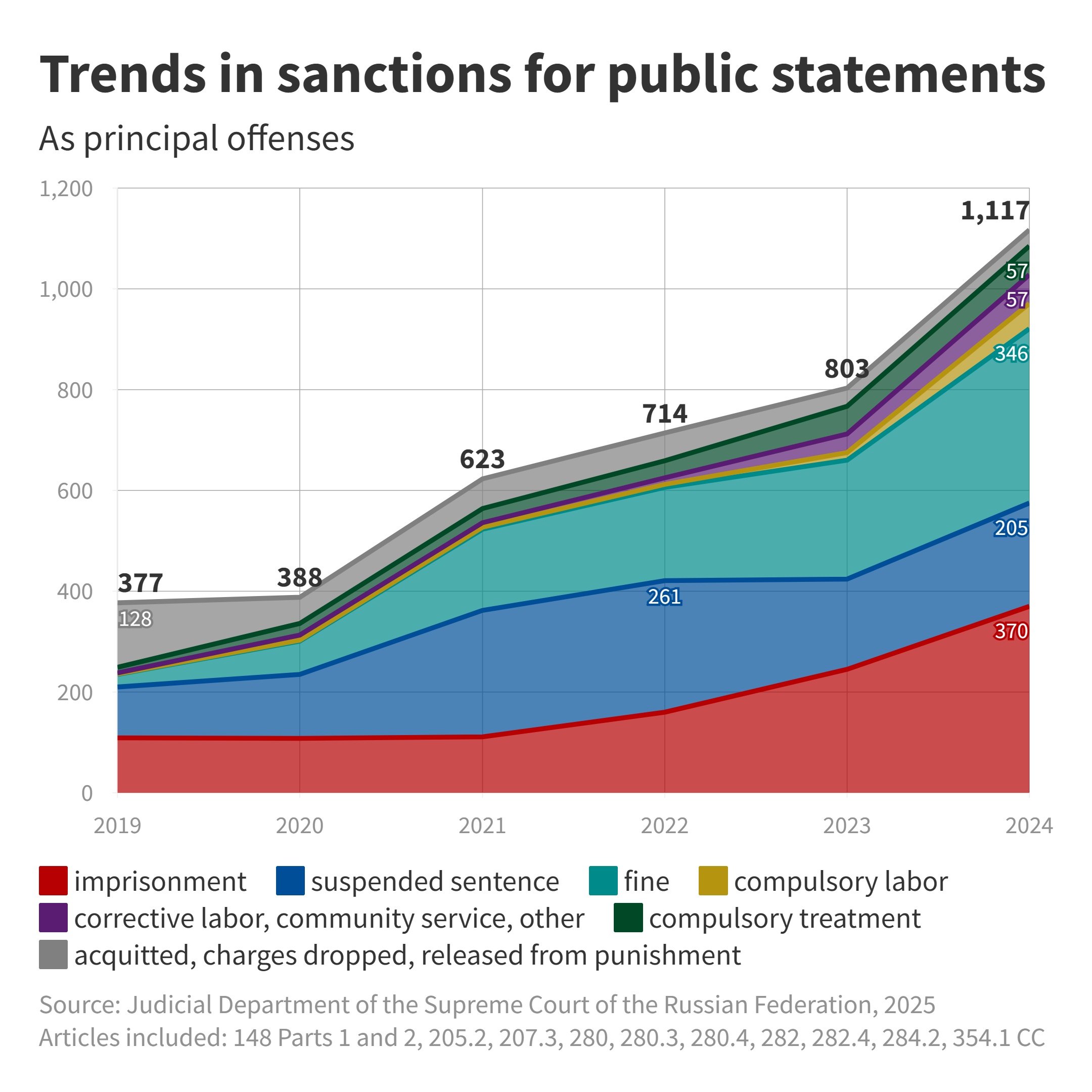

At the end of the chapter on sanctions for public speech, we will provide summary data on the 2024 application of all relevant criminal articles.

SOVA Center has written repeatedly about the problems associated with definitions and norms of Russian legislation related to the concepts of “extremism” and “terrorism.” However, there are definitely some instances, in which the state, in accordance with the norms of international law and the Russian Constitution, can legitimately prosecute public statements under criminal procedure as socially dangerous incitement.

It is not always possible to determine in which cases sanctions for “propaganda of terrorism or extremism” are justified and when they clearly violate rights and freedoms. Court decisions on such cases predominantly remain unpublished due to a ban on publishing the texts of judicial acts issued in cases “affecting the security of the state.” The information available from other sources is often insufficient to assess the legitimacy of these decisions.

Law enforcement related to criminal articles on incitement of hatred, propaganda of extremism, and propaganda of terrorism is non-transparent and, at the same time, has become increasingly repressive. First, the proceedings exhibit an accusatory bias, as courts rarely acknowledge the low probability that the incriminating statement will result in serious consequences. Next, a substantial proportion of convictions under these articles result in imprisonment, despite the availability of alternative penalties. SOVA Center believes that imprisonment, even in cases involving public calls for violence, is appropriate only for deliberate propaganda of violence (more or less systematic and having at least some chance of implementation) rather than isolated emotional outbursts.

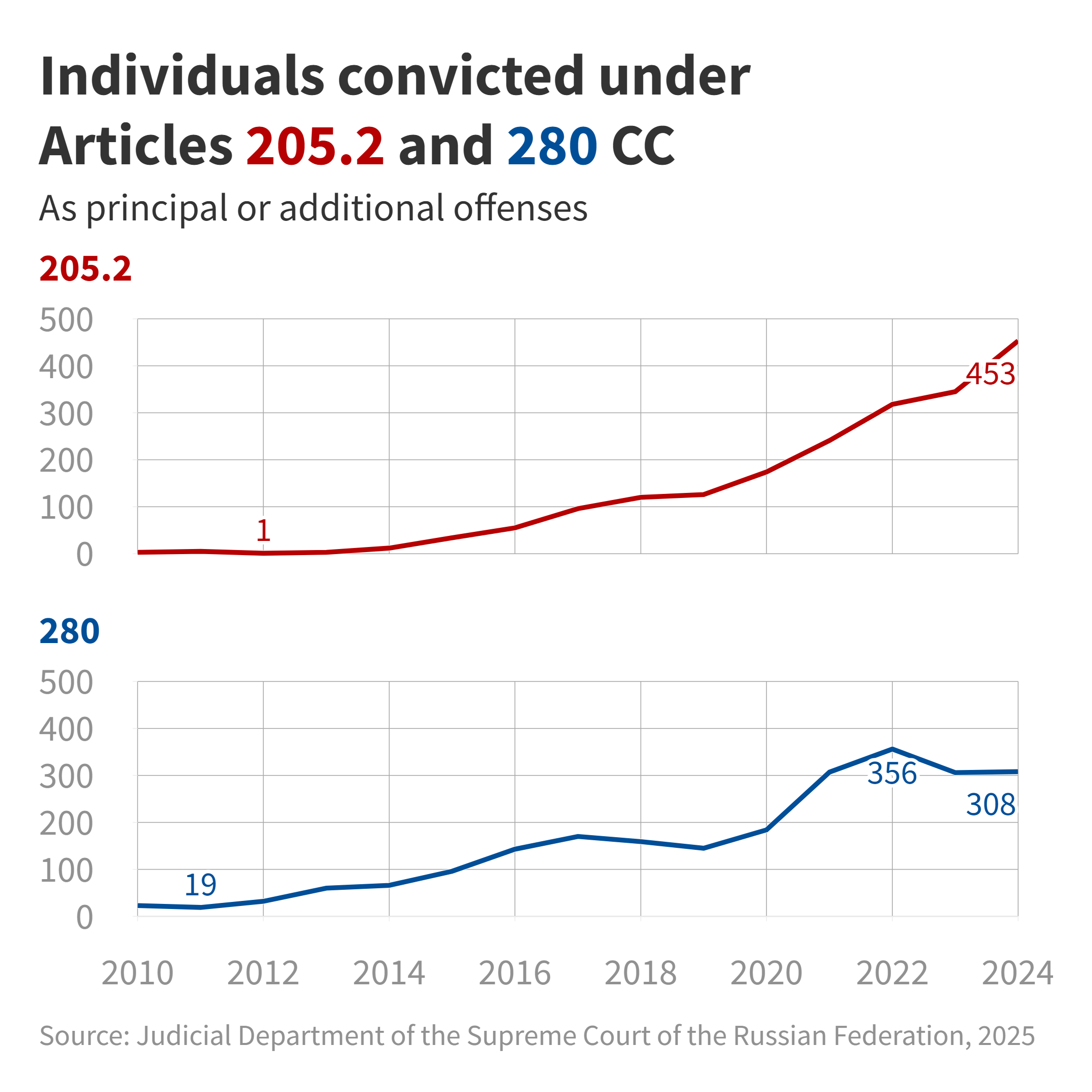

Article 2052 CC on Propaganda of Terrorism

According to the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, 453 people were convicted in 2024 under Article 2052 (public calls for terrorist acts, public justification of terrorism, or propaganda of terrorism): for 410 of them it was the principal offense, that is, the most serious allegation against them, and in 43 cases it was an additional charge.

Law enforcement numbers for this article grew steadily from 2012, increasing from a few to four and a half hundred cases per year, but the percentage of prison terms among all those sentenced under this article as the principal offense remained at 37–40%.

Of the 410 individuals convicted in 2024 under Article 205² CC as their principal offense, 152 were sentenced to imprisonment, while the majority (254) received fines; one was sentenced to compulsory labor, and four were released from punishment. In addition, 27 individuals were exempted from criminal liability on mental health grounds and referred for compulsory treatment.

Of the 453 individuals convicted under Article 205² CC in 2024, 54 were found guilty under Part 1, for offline statements, and 399 under Part 2, for statements made on the Internet.

At the time of writing, the SOVA database contained 139 court decisions against 144 people charged under Article 2052 CC. Among these, one individual was released from punishment, two were referred for compulsory treatment, and 141 people faced criminal sanctions. 22 sentences against 23 people were issued for cases initiated in 2024. In total, we have information on 190 cases against 204 people initiated in 2024 under this article.

Let us now examine the distribution of decisions under Article 2052 across the categories outlined above.

Our database for 2024 includes six sentences against six people convicted for their statements expressing ethnic xenophobia. For three of them, this was the only article cited in the judgement. In two cases, it was combined with Article 280 CC on calls for extremist activity, and in one case, with articles on violent crimes.

The sentences were issued for public anti-Semitic incitement, justification of violence against Russians during the Chechen wars, and approval of the actions committed by Andreas Breivik. Convicted offenders included one member of the network “Maniacs. Murder Cult” (Manyaki. Kult Ubiystv, MKU). However, his imprisonment sentence was imposed primarily for participating in two xenophobic attacks in April 2023.

We know of seven cases under this article for speech expressing ethnic xenophobia, initiated in 2024 against eight people. In two of these cases, courts issued their sentences by the end of 2024.

We have recorded 16 sentences under Article 205² for statements promoting or justifying violence on religious grounds, resulting in the conviction of 18 individuals, 12 of whom were charged solely under this article. In the remaining cases, it was combined with Article 2051 on involvement of others in terrorist activity, Article 2055 on involvement in a terrorist organization, and Article 280 CC.

The majority of convicted offenders faced sanctions for approving the actions of militant Islamists: the Crocus City Hall terrorist attack, attacks against a synagogue, churches, traffic police in Derbent and Makhachkala, and the actions of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and Katibat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (recognized as terrorist organizations).

In addition, three followers of the radical Islamic party Hizb ut-Tahrir faced punishment for promoting party ideology.

We learned of 19 criminal cases opened against 20 people under this article in 2024 for statements related to religion. One of these cases resulted in a conviction in 2024. All the defendants were charged with supporting Islamists, mainly for justifying the Crocus City Hall attack.

Statements directed against the authorities form the basis of 46 sentences under Article 2052 CC against 47 people recorded in our database. Of these, 29 people were convicted under this article alone. In ten cases, the charge combined it with Article 280 CC, in five cases – with paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC on the dissemination of “fakes” about the army motivated by hatred. In some cases, it was also used in combination with other criminal articles.[6]

Most of these sentences concerned calls for the violent overthrow of the Russian government, including reprisals against its prominent representatives (Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Peskov, Vyacheslav Volodin, Ramzan Kadyrov). The charges could also involve calls for the murder of governors, members of the United Russia party, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the FSB, etc. One of the convicted individuals had published an “execution list” naming 38 people.

In 2024, we recorded 50 criminal cases initiated under Article 2052 CC for statements against the authorities, involving 50 individuals. In five of these cases, the courts issued sentences within the same year.

Statements supporting violent or other illegal actions in favor of Ukraine formed the basis for 79 sentences against 81 individuals we recorded under Article 2052 CC. For 50 of them, this was the only article in their convictions, ten had it combined with paragraph “e” of Article 2073, six faced it in combination with Article 280, and five – with Article 2055. In some cases, sentences also included other criminal articles.[7]

Specifically, three Ukrainian public figures and politicians were convicted in absentia. They were also found guilty under other articles, including, in one instance, the extremely rarely used Article 354 Part 2 CC (calls for the initiation of a war of aggression).

The sentences were issued for publicly supporting the actions of organizations recognized as terrorist in Russia: the Azov Regiment, the Noman Çelebicihan Battalion, the Freedom of Russia Legion, and the Russian Volunteer Corps (in most sentences, the last two units are mentioned together), as well as for approving attacks by Ukrainian drones on Russian cities, raids in the Bryansk Region by the Freedom of Russia Legion, and the Russian Volunteer Corps, explosion on the Crimean Bridge, destruction of the Kakhovka Dam, the terrorist attack by Daria Trepova against war correspondent Vladlen Tatarsky, arson attacks on military commissariats, acts of sabotage, etc.

We recorded 92 criminal cases against 104 individuals opened in 2024 for statements related to Ukraine under this article. 13 of them resulted in convictions against 14 people in the same year.

It should be noted that 16 people convicted in 2024 under Article 2052 CC were found guilty for their anti-government and pro-Ukrainian statements simultaneously. Nine people faced prosecution for such statements in 2024, and the court managed to sentence one of them before the year ended. We took these cases into account in both categories.

We have classified one 2024 sentence as “other” – the sentence of Ufa resident Karina Garipova, who was also convicted under Article 2055 Part 2 CC (participating in a terrorist organization) for disseminating the “Columbine” ideology. Garipova was sentenced to five and a half years of imprisonment for sending materials about school murders to someone in a private message when she was 17 years old. It is not entirely clear why she was found guilty of publicly promoting terrorism. We know of four additional cases under Article 2052 opened in 2024 for promoting school murders. One of them was based on entries in the personal diary of a 14-year-old Izhevsk resident and may have been closed.

We have no information on the acts underlying eight of the sentences issued in 2024 under Article 205² CC. The same is true for 24 criminal cases initiated in 2024 under this article, two of which were tried in court in the same year.

The majority of sentences under Article 205² of the Criminal Code concerned online statements, including texts, videos, images, comments, and other materials posted on social media platforms and messaging services. Most often, they were posted on VKontakte, much less frequently – on Telegram and YouTube; in isolated cases, statements were posted on Odnoklassniki, LiveJournal, and Facebook. Offline acts led to prosecution far less frequently, with charges arising from conversations in detention (half of which involved religious statements), the distribution of leaflets or graffiti, statements made while intoxicated, altercations, and, in one case, a statement by a teacher during a class. Occasionally, a single case could involve charges for both offline and online statements.

The individual sentences for online and offline statements were distributed among the categories as follows:

| Statement Category |

Online |

Offline |

Online and Offline |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

5 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

| Religion |

7 |

9 |

2 |

18 |

| Against the Authorities |

40 |

4 |

3 |

47 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

66 |

14 |

2 |

82 |

| Other |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

8 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| Total |

111 |

24 |

7 |

142 |

Let us now examine the distribution of individual sentences under Article 2052 CC across types of penalty and categories of incriminating statements (in three cases, we have no information about the sanctions).

|

Statement Category |

Imprisonment |

Suspended Sentence |

Labor |

Fine |

Total Punished |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

4 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

| Religion |

16 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

18 |

| Against the Authorities |

32 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

47 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

58 |

0 |

2 |

21 |

81 |

| Other |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

6 |

| Total |

97 |

1 |

2 |

39 |

139 |

It is worth reiterating that the appropriateness of cases under Article 2052 CC is difficult to assess, since the statements that served as the basis for the charges are available only in a small number of cases. Therefore, the majority of sentences under this article in our database were classified as “we don’t know.” This is particularly true for sentences issued for conversations in detention: their exact content and scope are unknown or in doubt. The “other” category ranked second, as a significant percentage of cases were initiated over aggressive anti-government and pro-Ukrainian statements – political rather than xenophobic in nature. Please note that while such cases are included in our database, they are not published as news on the website. Sentences for propaganda of ethnic and religious xenophobia, coupled with approval of terrorist acts against the corresponding groups or against the authorities, were rated ”yes,” but constituted a clear minority under this article. We classified even fewer sentences under this article as clearly inappropriate – if the incriminating statement contained calls for violence, we did not classify the corresponding sentence as inappropriate unless we were completely sure that it posed no public danger.

In the category of religious statements, we classified as inappropriate the high-profile conviction of Moscow theater figures Yevgenia Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk, who were charged with justifying the activities of militant Islamists for their play about women who left to join militants in Syria. We classified three sentences for anti-government statements as inappropriate because, in our opinion, they contained no calls for real terrorist acts – for example, when they mentioned “impalement” of officials. In the category of statements related to events in Ukraine, we classified the following as inappropriate: the conviction of former Moscow municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov for a statement he made in a penal colony regarding the predictability of violence during armed hostilities, the conviction of activist Yaroslav Shirshikov for comments about the deaths of Vladlen Tatarsky and Darya Dugina that contained no aggressive calls; and the conviction in absentia against Andy Stone, the press secretary of the Meta corporation, for his tweet about a change in content filtering policy in connection with the armed conflict in Ukraine.

|

Statement Category |

Yes |

No |

Not Sure |

We Don’t Know |

Other |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

6 |

| Religion |

6 |

2 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

18 |

| Against the Authorities |

4 |

3 |

1 |

16 |

23 |

47 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

4 |

3 |

4 |

30 |

41 |

82 |

| Other |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

| Total |

16 |

8 |

6 |

60 |

52 |

142 |

Cases recorded by us and initiated in 2024 are distributed across the categories as follows:

| Statement Category |

Number of Cases |

Number of Persons Involved |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

7 |

8 |

| Religion |

19 |

20 |

| Against the Authorities |

50 |

50 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

93 |

105 |

|

Other |

6 |

6 |

| Unknown |

24 |

24 |

|

Total |

190 |

204 |

Of the 190 cases opened in 2024 under Article 2052 CC that are known to us, we consider seven to be clearly inappropriate. These include the case of pianist Pavel Kushnir, who called for an “anti-fascist revolution” and died in pretrial detention, as well as the case of Sergei Davidis, head of the political prisoners support program at the Memorial Human Rights Centre, who was charged with supporting the actions of the Azov Regiment by granting political prisoner status to the regiment’s captured fighters.

Article 280 CC on Calls for Extremist Activity

According to the Supreme Court's Judicial Department, 308 people were convicted in 2024 under Article 280 CC (public incitement to extremist activity). 215 of them had this article as a principal offense in their sentence, and 93 as an additional charge. It should be noted that this number is only two more than the previous year, when 306 people were convicted under this article.

Of the total of 308 convicted offenders, 19 people were found guilty under Article 280 Part 1, that is, for offline statements, and 289 people – under Part 2 for statements on the Internet.

Of the 215 individuals convicted in 2024 under Article 280 CC as their principal offense, 34 people were sentenced to imprisonment, 140 people – that is the largest group – to suspended sentences, one to restriction of liberty, 26 to compulsory labor, one to corrective labor, and two to community service, 10 people received fines, one was released from punishment, nine cases were dismissed by the courts, and eight people were exempted from criminal liability for mental health reasons and referred for compulsory treatment.

The SOVA Center database contains 91 court decisions from 2024 under Article 280 CC against 93 people. One case was closed due to the defendant’s death, and one individual was released from punishment due to illness; thus, sanctions were imposed on 91 people. 87 individuals were convicted under Part 2, and four under Part 1. Nine of these sentences were issued in cases initiated in the same year. In total, we know of 52 cases opened in 2024 under Article 280 CC against 54 people.

30 sentences against 30 individuals were related to expressions of ethnic xenophobia. For 24 offenders, this was the only charge, for three people it was combined with Article 2052 CC, for one person – with Article 282, and in one more case – with paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC.

These people faced sanctions for posting comments on social media and public messenger chats with aggressive statements against people from the Caucasus (3), Central Asia (2), Ukrainians (1), Russians (9, including justification of the terrorist attack in Crocus City Hall), non-Russians (1), Jews (3) and unspecified ethnic groups (16). It should be noted that the same case could involve statements against several ethnic groups.

We learned that 20 new criminal cases under this article for expressions of ethnic xenophobia were opened in 2024 against 22 people; five of them were sentenced in the same year.

Seven sentences against seven people were issued under Article 280 CC for statements calling for violent and other illegal actions based on religious xenophobia. For three people, this was the only article in the conviction; for three others, it was combined with Article 2052 CC, and in the remaining cases, it was combined with other articles.[8]

All but one of the convicted offenders were found guilty of online calls for violent actions, such as violence against people who follow Judaism or do not follow Islam. The case of blogger Sofia Angel-Barokko, a follower of the “ancient gods,” stands out – she faced sanctions for a YouTube video in which she claimed to be using magic to combat the dominance of Abrahamic religions associated with the cult of “Yahweh the Occupier.” Specifically, she claimed to have facilitated the shelling of Israel and the fires in Christian churches in Russia and Europe.

We have information on four new criminal cases opened in 2024 under Article 280 CC for religious xenophobia, none of which resulted in a conviction during the same year.

32 sentences involving 34 individuals were issued for statements against the authorities under Article 280 CC. Of these, 20 people were convicted only under this article, ten were also convicted under Article 2052 and three – also under Article 214 Part 2 CC on vandalism motivated by hatred. Their sentences could also include other articles.[9]

Materials posted on social media that called for violence against government officials (law enforcement officers and civil servants) were the most frequent law enforcement targets.

We also recorded 14 new criminal cases opened under Article 280 CC for statements against the authorities. In three of them, the courts issued sentences in the same year.

21 sentences against 21 individuals were issued for statements concerning the armed conflict with Ukraine under Article 280; for 13 people, this was the only article in their sentence. Five people had it combined with Article 2052 and three others – with Article 2073 CC; other charges could be present as well.[10]

The charges were predominantly based on materials calling for violent actions against Russian military personnel, as well as “Russians” or “citizens of Russia” (not as representatives of an ethnic community, but as political opponents), or supporters of the special military operation and the government’s foreign policy. Most of the defendants were convicted for publications not on VKontakte (as is usually the case), but on Telegram.

We know of 10 criminal cases initiated under Article 280 CC in 2024 for statements related to the events in Ukraine, one of which resulted in a conviction that same year.

For the eight sentences issued in 2024 under Article 280 CC, we have no information about the basis of the cases. The same is true for the four new criminal cases opened in 2024 under this article.

The distribution of the offenders convicted for online and offline statements across our categories was as follows:

| Statement Category |

Online |

Offline |

Online and Offline |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

30 |

0 |

0 |

30 |

| Religion |

6 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| Against the Authorities |

31 |

3 |

0 |

34 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

21 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

| Other |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

8 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| Total |

1 |

87 |

3 |

91 |

Let us now examine the distribution of offenders convicted under Article 280 by type of penalty across all categories of incriminating statements (we have no information about the penalty in three cases).

| Statement Category |

Imprisonment |

Suspended Sentence |

Labor |

Fine |

Total Punished |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

9 |

17 |

2 |

2 |

30 |

| Religion |

3 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

| Against the Authorities |

12 |

15 |

3 |

4 |

34 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

12 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

20 |

| Other |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

| Total |

33 |

41 |

7 |

7 |

88 |

We determined that most sentences known to us under Article 280 CC were issued appropriately. Indeed, charges under this article are most often associated with aggressive propaganda of ethnic or religious xenophobia. However, as in the case of Article 2052, the assessment of many sentences under Article 280 CC is problematic due to the lack of relevant information. Therefore, here too, we rated a significant portion of the sentences as “we don’t know.” The rating “other,” which we assigned to aggressive anti-government and pro-Ukrainian statements of a political nature, took third place.

We classified several sentences under this article as inappropriate. These include, for example, the widely discussed sentence of Igor Strelkov for his post about the failure to pay salaries to soldiers of two DPR Armed Forces regiments. In the post, he wrote that “execution by firing squad would not be enough” to punish those responsible for such situations – though he was unlikely to have meant this literally as a call for reprisals against the military leadership. Also notable is the sentence against three anarchists from Chita for their “Death to the Regime” graffiti on a garage. They were charged not only with vandalism motivated by hatred but also with incitement to extremism. In our view, this slogan is a typical example of an abstract anti-government statement that does not contain explicit calls for violence and therefore poses no significant public danger.

| Statement Category |

Yes |

No |

Not Sure |

We Don't Know |

Other |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

26 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

30 |

| Religion |

4 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

7 |

| Against the Authorities |

3 |

5 |

1 |

16 |

9 |

34 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

3 |

4 |

1 |

9 |

9 |

21 |

| Other |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

| Total |

30 |

5 |

2 |

37 |

17 |

91 |

The cases known to us under Article 280 CC, initiated in 2024, are distributed across our categories as follows:

| Statement Category |

Number of Cases |

Number of Persons Involved |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

20 |

22 |

| Religion |

4 |

4 |

| Against the Authorities |

14 |

14 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

8 |

8 |

| Other |

0 |

0 |

| Unknown |

10 |

10 |

| Total |

52 |

54 |

Notably, we did not rate the charges as clearly inappropriate in any of these cases.

Article 2804 СС on Calls for Actions That Threaten State Security

Article 2804, introduced into the Criminal Code in 2022, establishes liability for public calls for various actions that are considered a threat to state security. These actions are so diverse that the grounds for combining calls for them within a single provision remains unclear. Some indeed relate to state security – such as treason or sabotage – while others concern war crimes, ranging from failure to follow an order to mercenarism, or fall under provisions addressing public statements and activities not formally included in the lists of extremist or terrorist offenses (dissemination of false information about the armed forces or their repeated discrediting, participation in the activities of an “undesirable organization,” and so on). At the same time, Article 2804 also penalizes incitement to ordinary criminal offenses of varying gravity, such as illegal possession of weapons, organized criminal activity, violation of export controls, etc., up to and including calls for receiving and giving bribes.

While in 2023, the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court reported four people convicted under Article 2804 CC, there were already 18 of them in 2024. 16 offenders were found guilty under Part 2 of this article (that is, with aggravating circumstances), and two – under Part 3 (that is, for a crime committed by an organized group).

Of the 14 individuals convicted under this article as their principal offense, six were sentenced to imprisonment, three received suspended sentences, and five were fined.

The SOVA Center database contains 12 relevant sentences from 2024 against 12 people. In six cases, Article 2804 CC was the only charge; in four cases, it was combined with Article 2052 CC. The offenders could have also faced charges under other articles.[11] Four of these sentences were issued in cases initiated in 2024. In total, we know of 11 cases opened in 2024 under this article.

In all 12 cases, paragraph “c” of Article 280 Part 4 CC was also applied, that is, the offenders faced punishment for disseminating their incitement on the Internet.

In the cases when we had at least partial information on the content of the incriminating statements, they pertained to the “special military operation” in one way or another, including calls for the destruction of military registration and enlistment offices, sabotage, informing Ukraine about the location of Russian troops, donations to the Armed Forces of Ukraine or the Freedom of Russia Legion, providing material support to Ukraine, violence against the Russian authorities (including employees of state security and law enforcement agencies), and refusal to be drafted or participate in military operations against Ukraine. Thus, the scope of this article’s application largely overlaps with the elements and coverage of Articles 205² and 280 CC, despite the text of the provision indicating otherwise.[12]

Eight of the 12 people were sentenced to imprisonment for a term of three years or more (the upper limit depended on other articles in the sentence), one received a suspended sentence, two were fined by the courts, and in one case, we have no information about the sanctions.

The six sentences for which we had sufficient information were not based on incitement to ethnic or religious xenophobia, but all involved calls for illegal activity. We therefore categorized them as “other” in terms of appropriateness. Insufficient information was available to evaluate the remaining six convictions.

Among the cases brought under Article 2804 CC in 2024, one seems clearly inappropriate – the case of the anti-war sermon of Nikolai Romanyuk, the pastor of the Holy Trinity Pentecostal church in Balashikha. In our opinion, Romanyuk did not call for any illegal actions. The 62-year-old pastor, arrested in the fall of 2024, remained in pre-trial detention at the time of writing this report.

Article 2824 СС on Displaying Prohibited Symbols

Article 2824 CC on repeated display of prohibited symbols was included in the Criminal Code in 2022. It establishes criminal liability for individuals previously sanctioned under Article 20.3 CAO[13] who commit a similar offense. According to Article 4.6 CAO, an offender is considered to have been punished within one year from the date the decision to impose the sanction enters into force or is executed.

In 2023, the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court reported 40 convictions under this article. In 2024, the number rose to 131. For comparison, in the same year courts of first instance sanctioned approximately 4,717 individuals under Article 20.3 of the CAO – an all-time high.

All offenders convicted under Article 2824 СС were sentenced under Part 1 in connection with the propaganda or display of prohibited symbols and not for their production or sale punishable under Part 2.

Of the 127 individuals convicted under Article 2824 as their principal offense, 66 people were imprisoned, 20 received suspended prison sentences, one person received a suspended sentence other than imprisonment, seven were sentenced to compulsory labor, 13 to corrective labor, 18 to community service, one was fined, and one individual was released from punishment by the court. One case was dismissed, and one person was referred for compulsory treatment.

The SOVA database for 2024 included 57 sentences under Article 2824 Part 1 CC against 56 people (one of them was sentenced twice under this article within a year). We know that the person referred for compulsory treatment was prosecuted for an anti-Semitic publication. The majority of the convicted offenders were sentenced under this article only; for three individuals it was combined with other articles.[14] 19 of the 57 sentences known to us were issued in cases initiated in 2024. In total, we have information on approximately 67 criminal cases opened in 2024 under Article 2824 CC.

Just over half of the sentences we recorded under this article concerned the display of symbols associated with the propaganda of ethnic xenophobia, for which 30 individuals were convicted. One person, an inmate of a penal colony in Kostroma, was convicted twice. Eighteen offenders were punished for displaying prohibited symbols offline – mostly tattoos with Nazi imagery – six of them while serving sentences in places of imprisonment. Twelve individuals displayed Nazi symbols on social media.

Among those convicted were well-known figures in the far-right community, including Yevgeny Breslavsky, former leader of the Novosibirsk Skinhead Unity association, and Andrei Razin (aka Chibis, Chinarik), leader of the neo-Nazi gang White Scouts from St. Petersburg – both were convicted of displaying their tattoos. The leader of a soccer fan group from Tula faced sanctions for the symbols displayed on his T-shirt, and far-right trash blogger Daniil Matsankov (Svarogov) – for a video with Nazi symbols posted on Telegram.

We know of 30 cases opened in 2024 for displaying far-right symbols.

22 people were convicted for demonstrating the symbols of Prisoners’ Criminal Unity (Arestantskoe Ugolovnoe Yedinstvo, AUE), most often an eight-pointed star (“a compass rose”). One of them was sentenced twice, as we already mentioned above. AUE is a criminal subculture recognized as an extremist organization on unclear grounds in 2020. Thus, both inmates and those already released can face prosecution for promoting the ideology of the criminal world and demonstrating the corresponding symbols. In 2024, inmates were punished mostly for repeatedly demonstrating their tattoos with the corresponding symbols in places of imprisonment to other inmates. It is quite difficult to hide tattoos in prison conditions, even if a person would like to do so; furthermore, jails and prisons provide no means of removing a tattoo. Only four people were convicted for demonstrating AUE symbols on social networks.

We have information about at least thirty criminal cases initiated in 2024 for displaying AUE symbols.

We know of only one criminal sentence for repeated display of the Ukrainian slogan “Glory to Ukraine,” which often incurred administrative sanctions in 2024 under Article 20.3 CAO. We recorded only one such case newly opened in 2024. We also know of one case initiated for repeated display of the anti-war white-blue-white flag (unrelated to promoting the Freedom of Russia Legion). Additionally, some displays of Nazi symbols were intended as criticism against the Russian authorities, in particular, for their military actions in Ukraine. For example, Nazi symbols could be shown next to the symbols of the “special military operation.” We know of at least two such convictions, and two new cases were opened in 2024.

Two people were convicted for displaying unspecified symbols, and two similar cases were reportedly opened in 2024.

The distribution of sentences for displaying symbols online and offline across our categories was as follows:

| Symbol Category |

Online |

Offline |

Online and Offline |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

12 |

20 |

0 |

32 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

| Other (AUE) |

4 |

18 |

1 |

23 |

| Unknown |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| Total |

22 |

34 |

1 |

57 |

Now let us review the distribution of sentences under Article 2824 CC by type of penalty and categories of incriminating statements (one person was convicted twice; the penalty is unknown in three cases). Notably, over half of those convicted were sentenced to imprisonment, most often because the offenses were committed while they were already serving a sentence and had prior criminal records.

| Symbol Category |

Imprisonment |

Suspended Sentence |

Labor |

Fine |

Total Punished |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

17 |

5 |

6 |

0 |

31 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| Other (AUE) |

15 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

23 |

| Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| Total |

31 |

7 |

13 |

1 |

53 |

We classify sanctions for displaying Nazi and other far-right symbols for the purpose of Nazi propaganda as appropriate, while sanctions for displaying a swastika to criticize the authorities, as in the case of “citizen of the USSR” Vladimir Nesonov from Stavropol, are rated as inappropriate. We view sentences for AUE symbols as “other,” since the ideology of the criminal world is not xenophobic per se; however, in several cases, both Nazi symbols and AUE symbols were displayed simultaneously, and we rated the sentences in such cases as appropriate. A special case is the sentence issued to artist Vasily Slonov from Krasnoyarsk for creating and displaying tumbler dolls with prison tattoos. He received a year of corrective labor. In our opinion, this is an example of inappropriate sanctions for artistic expression.

Overall, according to suitability within categories, the 2024 sentences were distributed as follows:

| Symbol Category |

Yes |

No |

Not Sure |

We Don't Know |

Other |

Total |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

28 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

32 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| Other (AUE) |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

23 |

| Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

| Total |

29 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

19 |

57 |

Of the 67 cases known to us that were opened in 2024, we classified at least six as inappropriate, including, for example, the case against Alexei Sokolov from Yekaterinburg, prosecuted for links with Facebook icons displayed on the “Human Rights Defenders of the Urals” website and Telegram channel.

The cases we recorded as initiated in 2024 under Article 2824 CC fall into the following categories:

| Symbol Category |

Number of Cases |

Number of Persons Involved |

| Ethnic Xenophobia |

30 |

30 |

| Pro-Ukrainian |

4 |

4 |

| Other (Including AUE) |

31 |

30 |

| Unknown |

2 |

2 |

| Total |

67 |

66 |

Article 2073 CC on the Dissemination of Fakes about the Activities of Armed Forces and Government Agencies

According to the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, 90 individuals were convicted in 2024 under Article 2073 CC, which penalizes disseminating false information about the use of the Russian armed forces and the activities of its government agencies abroad. This marks an increase from 2023, when 65 people were convicted.

In 2024, according to the Judicial Department, 17 people were punished under Part 1 of Article 207³ CC, and 73 people under Part 2, which applies in cases involving aggravating circumstances.

Of the 15 individuals convicted under Part 1 of this article as the principal offense, one person received a suspended sentence, eight were sentenced to corrective labor, five to a fine, and one person was released from punishment. The criminal prosecution of another defendant was terminated, while two were exempted from liability and referred for compulsory treatment.

As for Part 2, 67 people were convicted under it as the principal offense. Among those, 62 offenders were sentenced to imprisonment, one received a suspended sentence, one was sentenced to compulsory labor, and three were fined. Three defendants were referred by the courts for forced treatment.

SOVA Center tracks for its database the use of paragraph “e” only of Article 2073 Part 2 CC – the dissemination of fakes about the activities of the army and government agencies motivated by hatred. We recorded 79 such sentences against the same number of people in 2024. Our number exceeds the one provided by the Judicial Department, since the latter only reports decisions that have entered into force. Two defendants were referred for compulsory treatment.

This norm constituted the only charge for 57 individuals. The sentences for 22 other defendants also included other articles, most often Article 2052 CC (ten people), other paragraphs of Article 2073 Part 2 CC (seven people), as well as Articles 280, 282, 2803, and 2804 CC.

17 out of 79 sentences issued in 2024 pertained to court cases initiated in 2024. In total, we recorded 61 new cases under this article opened against 67 defendants in 2024.

The charges under Article 2073 CC are based on disseminating information about armed actions in Ukraine that contradicts the official account provided by the Ministry of Defense, most often about the actions of Russian military personnel. Dissemination of such information, when combined with criticism of the special military operation – including allegations of war crimes by Russian military personnel or expressions of a negative attitude toward the Russian authorities, the state, or its citizens – falls under paragraph “e” of Part 2, Article 207³ CC. Such statements are interpreted by law enforcement agencies and courts as manifestations of ideological, political, or national hatred, regardless of their form or tone.

Defendants faced charges for sharing videos, various media materials, social media posts, comments, etc. In one case, the prosecution was triggered by publication of a book (a collection of interviews with Russians who hold anti-war views), and in several cases – by personal conversations, particularly, conversations with cellmates in places of imprisonment.

Of the sentences known to us, 73 were for online statements, three for offline statements, two for both, and one case lacked information.

73 individuals were sentenced to imprisonment, one received a suspended sentence, one was sentenced to compulsory labor, and one was fined (three million rubles); in three cases, we have no information on the penalty. Paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC provides for very severe sanctions – most often, convicted offenders faced eight to eight and a half years of imprisonment. Courts also imposed long terms of imprisonment on women, even elderly ones: for example, 59-year-old nurse Olga Menshikh was sentenced to eight years in a penal colony, and 68-year-old pediatrician Nadezhda Buyanova – to five and a half years.

On the other hand, it is worth noting that courts consider cases under Article 2073 Part 2 CC even if defendants are not present. Of the 79 sentences we know of, 38 – nearly half – were issued in absentia against individuals residing outside Russia, with the majority (33) handed down by Moscow courts. Four of the sentences concerned Ukrainian politicians and journalists. More frequently, however, they pertained to emigrants, including well-known public figures: politicians, public figures, journalists, and actors. Such decisions are likely intended to be demonstrative – to vilify Ukrainians and to send a message to those who have “left,” discouraging emigrants from publicly criticizing the Russian authorities.

Four people convicted in 2022–2024 under paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC were released in 2024. Politicians Ilya Yashin and Vladimir Kara-Murza (he was also found guilty under several other CC articles), journalist Alsu Kurmasheva and artist Alexandra Skochilenko were transferred to Western countries as part of a prisoner exchange.

We believe that the motive of ideological and political hatred has been used with Article 2073 CC in a clearly inappropriate manner. Those who publish information about military actions in Ukraine that diverges from the official version are, unsurprisingly, most often expressing ideological and political disagreement with the course pursued by the authorities. In most such cases, these statements constitute political criticism. Therefore, we consider sanctions under Article 207³ CC to be inappropriate in all cases where the charge is unrelated to violence or direct calls for it. We classified 75 sentences under paragraph “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 CC as inappropriate. We also found one case difficult to evaluate and classified three as “other,” since they dealt with calls for violence in the context of an armed conflict.

Article 2803 CC on Discrediting Armed Forces and Government Agencies

According to the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, 68 people faced sanctions in 2024 under Article 2803 CC on repeated discrediting of the use of the Russian armed forces and the activities of its state agencies abroad, including five individuals who had this article as their additional charge. This total exceeds the numbers from 2023, when 50 people were convicted.

A person is held liable for a repeated offense under Article 2803 Part 1 CC, within a year after the imposition of a penalty under Article 20.3.3 CAO on discrediting the army or government agencies. The statistics on the application of this article in 2023–2024 can be found in our report on administrative law enforcement. We will only note that these numbers have been falling; courts of first instance imposed sanctions 1,805 times in 2024, compared to 4,440 in 2022 and 2,361 in 2023.

According to the Judicial Department, 66 people faced sanctions under Article 2803 Part 1 CC in 2024, and two individuals faced punishment under Part 2, that is, their actions caused harm to health or property. Of the 63 convicted under this article as their principal offense, 13 people were imprisoned, 12 individuals received suspended sentences, three were sentenced to compulsory labor, 32 were fined and three persons were released from punishment. The criminal prosecution of two defendants was terminated.

The SOVA Center database includes 81 court decisions against 84 people issued under Article 2803 CC in 2024. This number is higher than the one provided by the Judicial Department, since we include all sentences issued during the year, while the Department only includes the ones that have entered into force. 25 of the 2024 sentences known to us were issued in cases initiated in 2024. In total, we know of 63 cases opened in 2024 against the same number of people (the investigation dismissed one of them). 59 of these cases were initiated under Article 2803 Part 1 CC, and four under Part 2. Notably, the number of people known to have faced criminal charges under this article is significantly lower than a year earlier, when, according to the OVD-Info project, the total reached at least 107 individuals.

77 people faced punishment, the court dropped the charges against five individuals due to the expiry of the limitation period, one person only received a court fine (i.e., a fine without a criminal record), and one was referred for compulsory treatment. In addition to the convicted individuals reported by the Judicial Department, we know of twelve more who face prison terms and two who were sentenced to compulsory labor. The maximum penalty issued under Article 2803 Part 1 CC (in the absence of other charges and aggravating circumstances) was two years of imprisonment.

Article 2803 CC was the only charge in 57 cases, while in another 20 cases it was combined with other articles: in four cases with Article 2073, in six cases with articles on violence and/or destruction of property, and in three cases with Article 2824. In isolated cases, sentences also included Articles 2822 and 2823 on participation in an extremist organization and its financing, Article 3541, Article 213 on hooliganism, Article 214 CC on vandalism, etc.

All cases we recorded under Article 2803 CC are related to statements about the events in Ukraine. Most often, charges are brought for online anti-war statements. However, some cases involve offline remarks to audiences of various sizes, the display of posters, the distribution of printed propaganda materials, etc.

In practice, anti-war graffiti often result in liability under Article 280³ Part 2 of the Criminal Code; at the same time, charges may also be brought under Article 214 on vandalism. Liability under Part 2 occurs in case of bodily harm, and we know of one such sentence in 2024. Four people beat up a veteran of the special military operation and, in addition to articles on the use of violence, were convicted under Article 2803 Part 2 CC.

Of the sentences known to us, 59 were handed down for online statements, twelve (against 15 people) for offline statements, and five for both types of speech. We lack information on five other convictions.

We are aware of only one case in which a court factored in the motive of political and ideological hatred in its sentence for repeated discreditation. This decision was made by the Golovinsky District Court of Moscow during the retrial of Oleg Orlov, the co-chairman of the Memorial Human Rights Centre. He was sentenced to two and a half years of imprisonment but was later released as a result of a prisoner exchange between Russia and Western countries.

In general, we view sanctions for discrediting the actions of the Russian army and government agencies abroad as an unjustified restriction of freedom of speech aimed at suppressing criticism of these institutions. Therefore, we deem prosecution under Article 280³ CC inappropriate in all cases not involving violence or direct calls for it. There was one sentence under this article in 2024, which we did not consider inappropriate – against the above-mentioned four citizens who beat up a special military operation participant. Reportedly, the conflict arose “due to their hostility toward military actions in Ukraine.”

Article 282 CC on Incitement to Hatred