Summary

Criminal Prosecution :

For Public Statements : For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and

Banned Organizations

Federal List of Extremist Materials

Banning Organizations as Extremist

Prosecution for Administrative

Offences

Crime and punishment statistics

This report focuses on countering the incitement of hatred, calls for violent action and political activity of radical groups, primarily nationalists, through the use of anti-extremism legislation. We are primarily interested in countering nationalism and xenophobia, but in reality the government's anti-extremist policy is focused far more broadly, as reflected in the report. This counteraction is based on a number of articles of both the Criminal Code (CC) and the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO), on mechanisms for banning organizations and “informational materials,” blocking online content, etc.

This report does not address countering hate crimes: they were covered in an earlier report[1] . Another report, published in parallel, examines the cases of law enforcement that we consider unlawful and inappropriate; it also examines the legislative innovations of the past year in the field of anti-extremism[2] .

Summary

Criminal prosecutions for speech in 2022 remained at about the same level as before. Although we see some quantitative growth in the number of people convicted “for words only,” this growth is not as radical as the year before. The trends we noted last year of an increase in the proportion of convictions for speaking out against the authorities and the number of those convicted under the articles for calls to terrorist actions continued in 2022. The number of those punished under administrative articles also rose. As before, it was mainly due to the article of the Administrative Code on displaying prohibited symbols, not counting the article on “discrediting,” the application of which we fully qualify as unlawful.

Law enforcement in relation to participation in extremist and terrorist communities and organizations, as opposed to prosecution for public statements, has grown very noticeably. The diversity of those charged with these articles of the Criminal Code has also increased, even excluding the unlawful cases. In 2022, members of far-right groups such as the National Revival Path of Russian Patriotism (NVSRP), the United Russian National Party (ERNP), the Astrakhan National Movement, as well as a number of members of “Soviet Citizens” groups, starting with self-proclaimed Soviet President Sergei Taraskin, were convicted. As expected, convictions were handed down for involvement in banned Ukrainian organizations, radical Islamist groups, and, finally, for involvement in the A.U.E. prison subculture, which for some reason was recognized as extremist. Both radical far-right members of the Sakhalin Tactical Nationalists Club (S.T.C.N.) and radical Islamists from ISIS were convicted under articles for participation in terrorist communities and organizations.

The list of extremist organizations was actively expanded in 2022 to include both far-right organizations, the most prominent of which were Men's State and Nevograd, and Ukrainian and radical Islamist organizations.

This trend is likely to intensify: throughout the past year, law-enforcement officers continued to hunt down members of the people-hating group M.K.U [Maniacs. The Cult of Murders]. In 2022 the first sentences for members of right-wing groups previously detained in connection with M.K.U. were also passed, but many sentences are still to come. And in early 2023, the M.K.U. was recognized as a terrorist organization.

Law enforcement in 2022, which took place almost all year against the backdrop of large-scale military operations in Ukraine, was certainly affected by the latter. But since criminal investigations and the preparation of measures to ban organizations are lengthy processes, court decisions that were made mostly concerned cases opened earlier. We saw how the rapid acceleration of anti-extremist activity, which apparently began in 2020, resulted in a sharp increase in the number of court decisions in 2021. On the other hand, it seems that in 2021, more cases on the activities of organized groups were initiated, and the new cases on “extremist statements” showed at the same time a quantitative stabilization. However, judging by the fact that in 2022, the number of registered “extremist crimes” as a whole (these include violent crimes, public statements, and participation in groups) grew by one and a half times[3], in 2023 we will see another significant increase in the number of convictions.

Criminal Prosecution

For Public Statements

By persecution for public “extremist statements” we mean statements that were qualified by law enforcement agencies and courts under articles 282 (incitement to hatred), 280 (calls for extremist activity), 2801 (calls for separatism), 2052 (calls for terrorist activity and justification thereof), 3541 (rehabilitation of Nazi crimes, desecration of symbols of military glory, insulting veterans, etc.) and Parts 1 and 2 of Article 148 (the so-called insults of religious believers' feelings) of the Criminal Code. This does not comply with the official interpretation of the term.[4] Thus, Article 2052 is categorized as terrorism, but too often it has little to do with terrorism itself, and we consider it within the broader concept of extremism. Articles 148 and 3541 are officially considered “extremist” only when a hate motive is established, but they are so closely related to extremism that we prefer to consider them at all times. Of course, some other articles of the Criminal Code may also be classified as “extremist statements” if a “hate motive” is established as an aggravating circumstance, but we are not aware of any such cases with regards to this report.[5]

Taking account of the new offenses related to public statements, which appeared in the Criminal Code in 2022, was problematic. We plan to take into account Art. 2824 (repeated display of prohibited symbols), but there have been no convictions under this article yet. We also take into account Art. 2803 (repeatedly discrediting the actions of the army and state officials abroad), but we consider this article to be completely unlawful, and its enforcement is addressed in the report on “inappropriate anti-extremism.” As for Art. 2073 (on “fakes” concerning the actions of the army and state officials abroad), it does not generally seem to fall in the “extremist” category, since it is more of a form of slander. We are against the appearance of another article on slander in the Criminal Code, but here we are more interested in the fact that the relevant act may be qualified, among other things, as committed for reasons of racial, political, or other animosity (Paragraph D, Part 2) – and then it is classified as “extremist crime.” We proceed from the premise that the statements for which one is prosecuted under Art. 2073, are political, hence, we consider it unreasonable to apply the motive of political or ideological enmity to them as an aggravating circumstance, since any political statement is in some way hostile to political opponents. Accordingly, our report can only take into account those sentences under paragraph D, Part 2 of Article 2073 of the Criminal Code where the motive includes some other enmity (for example, ethnic).

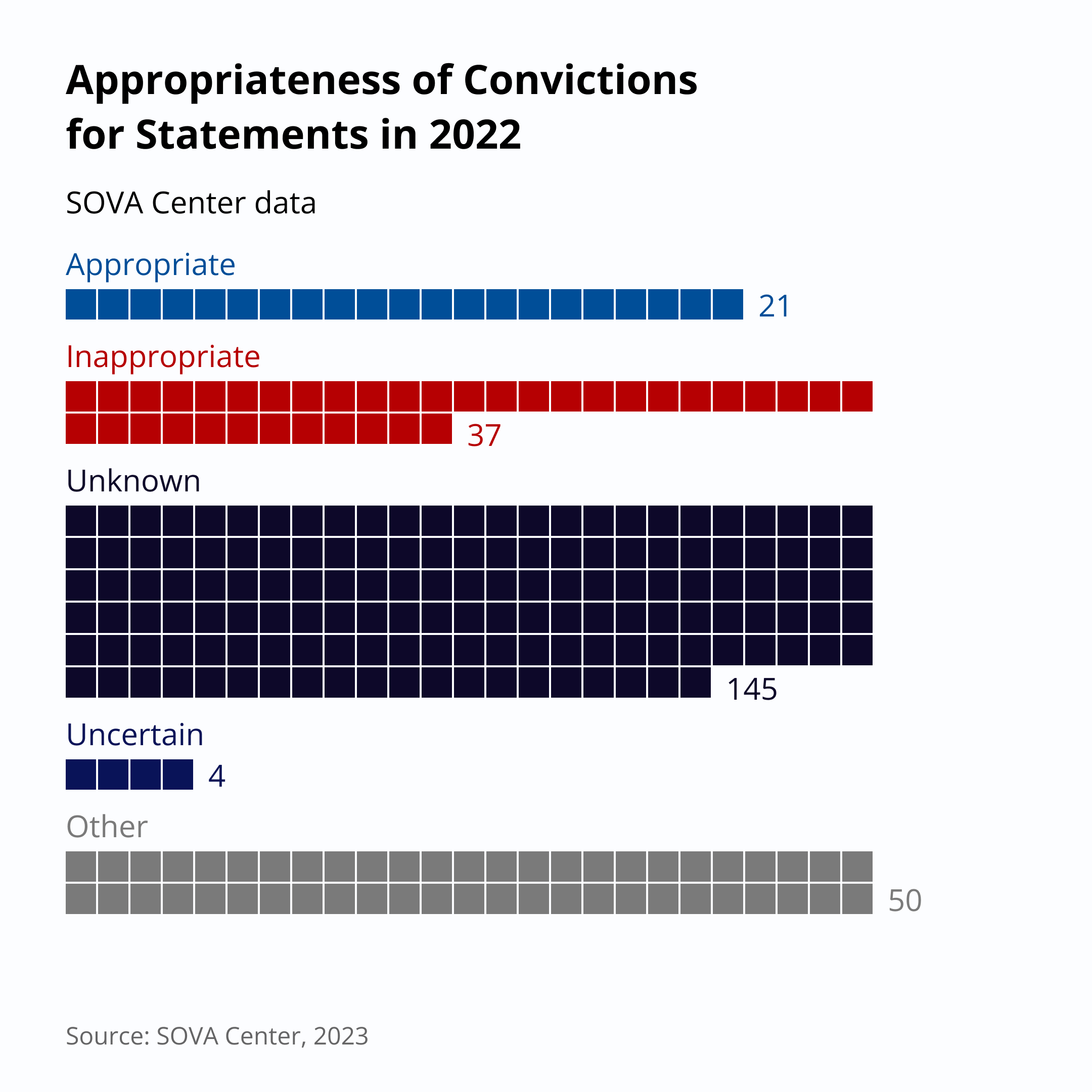

In 2022, according to our incomplete data, the number of convictions for “extremist statements” increased slightly compared to 2021. SOVA Center has information about 208 sentences against 220 people in 62 regions of the country.[6] In 2021, we have information about 209 such sentences against 212 people in 47 regions. As is customary, we do not include in this report the sentences that we consider unlawful (all exceptions are mentioned below): in 2022, it was 39 sentences against 40 people[7]. Thus, this report includes the sentences that we consider lawful and appropriate, those whose appropriateness we doubt, those about which we do not know enough to assess their lawfulness, as well as those that are not clearly unlawful and have nothing to do with countering nationalism and xenophobia.

The statistics do not include any acquittals (none in 2022, one in 2021). In addition, we do not include in the statistics and record separately the instances of release from criminal liability with payment of court fines (an alternative introduced in Russian law in 2016). No such releases from liability with payment of court fines were recorded in 2022; in 2021, three such instances occurred.

Overall, we know of only about half of the “extremist statements” cases. According to the data posted on the Supreme Court website,[8] just in the first half of 2022, 267 people were convicted of “extremist statements,” and this number includes only those for whom this was the main charge.[9] And this is more than the 212 that were convicted during the same period a year earlier.[10] In this report, we use our own data, because the Supreme Court data does not allow for meaningful analysis and is very late.

Since 2018, we have been using a more detailed approach to conviction classification[11].

We deem appropriate those convictions where we have seen the statements, or are at least familiar with their contents, and believe that the courts have passed convictions in accordance with the law. In our assessment of appropriateness and lawfulness, we apply six-part assessment of the public danger of public statements[12], supported by the Russian Supreme Court and the UN Human Rights Council almost in its entirety.

In 2022, we considered 16 convictions against 21 individuals lawful (eight convictions against 10 people in 2021), for instance, sentences for the leader of the Belaya Ukhta movement in Komi or the Chita follower of Maniacs. The Cult of Murders (M.K.U.), recognized as terrorist in 2023[13]. The sentences handed down to these individuals included episodes of videos with scenes of violence[14] and calls for xenophobic attacks (mostly on VKontakte) and “instructions to commit extremist acts.” Given the aggressive readership of such appeals and the fact that we are talking about large communities on the social network popular with young people or the rapidly gaining in popularity Telegram messenger, such appeals are clearly dangerous.

Unfortunately, in too many cases – marked as “Unknown” (147 convictions against 148 people) – we do not know enough or don't know at all about the content of the incriminating material and therefore cannot assess the appropriateness of the court decisions.

The “Uncertain” category (four convictions against four people) includes those court decisions that we find difficult to evaluate: for example, we tend to consider one of the episodes of the prosecution as lawful and another as not, or we have reasons to consider the sentence to be unlawful, but there is not enough information to make a confident judgment about it.

The “Other” category (44 verdicts against 50 people) includes sentences under “extremist” articles of the Criminal Code, which we cannot definitely consider unlawful and which cannot be attributed to anti-nationalism and xenophobia. Rather, these sentences were lawful (mostly for calling for attacks on government officials), but in some cases we cannot judge the appropriateness due to a lack of information.

Some sentences may fall into more than one category if different episodes are evaluated differently.

The comments below exclude the sentences that we consider unlawful.

According to SOVA Center data, Article 280 of the CC was applied in slightly more than half of the sentences[15]: in 118 sentences against 120 people; for 81 of these people, this article was the only charge. It could, for example, be combined with other charges, both “extremist,” such as Art. 2822 (Participation in an extremist organization), and ordinary criminal articles, for example, Art. 222 of the CC (illegal storage of firearms) or Art. 359 of the CC (mercenaryism).

Art. 2052 of the CC (public calls for terrorist activities) was applied even more actively than in previous years. According to the Supreme Court data, in the first half of the past year, a total of 126 people were convicted under this article (73 in the first half of 2021). SOVA Center is aware of 88 convictions of 95 people (not counting wrongful convictions). In 60 cases, this was the only article applied in the conviction. In another 15 cases, it was applied in combination with Art. 280 of the CC, in one other case with Art. 282 of the CC (incitement to hatred), and in another case – with both of these articles. And in a number of cases this article was combined with other anti-terrorism articles of the Criminal Code, such as Part 1.1 of Article 2051 of the CC (involvement in terrorist activities) and Article 2055 of the CC (participation in the activities of a terrorist organization). For example, in Rostov-on-Don, four ISIS supporters were convicted under a whole range of anti-terrorism articles for their involvement in organizing and preparing terrorist acts during the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

The application of this article is getting more wide-reaching, politically, with every passing year. Whereas it was applied exclusively to radical Islamists only a few years ago, in the past year it was also used against radical far-right (the leader of the already mentioned White City 31 organization), “citizens of the USSR,”[16] representatives of leftist organizations, and other people whose political views are unknown to us.

In 2022, 32 people were convicted for radical Islamist statements, including calls to join ISIS or to support other Islamist terrorist organizations, including propaganda in penal colonies and other places of confinement (not less than seven cases). Three sentences were handed down for supporting the Christchurch (New Zealand) mosque terrorist attacks, committed on March 5, 2019. Nine people were punished for justifying the actions of Mikhail Zhlobitsky, who committed a terrorist attack in the reception room of the Arkhangelsk Oblast FSB building, and calling for such actions to be repeated.

Art. 282 of the CC was used in 19 sentences known to us against 19 people. In 14 of them, it was the only charge. According to reports from prosecutors' offices, all of these people had previously been held administratively liable under Article 20.3.1 of the Administrative Code, similar in wording (yet for some people, Part 2 of the Article was applied for incitement to violence).

In this report, we note 16 convictions of 19 people in which Art. 3541 of the CC (rehabilitation of Nazism) appeared; for 13 of them, it was the only article in their sentence. In most cases, people were punished for publishing various materials (mostly statements and comments, and in one case a drawing and a song) on social networks and in messengers (two cases), which contained “approval of Nazi actions and denial of the facts established by the verdict of the International Military Tribunal for the trial and punishment of the major war criminals” and some of which endorsed the Holocaust. One person held similar conversations with other inmates in the detention center. Two wrote offensive graffiti on the grave of a veteran; they were also charged with Article 244 of the Criminal Code (desecration of burial sites).

Part 1 of Art. 148 of the CC (Public actions expressing clear disrespect for society and committed for the purpose of insulting the religious feelings of believers) was applied in two sentences against two people. Both times it was not the only article in the verdict: in one case it was combined with Article 280, and in the other – with Article 282 of the CC.

Part 3 of Art. 212 of the CC (calls for mass riots) was applied to one person in conjunction with Art. 280 of the CC: an inmate of a penal colony shouted slogans from the window calling for attacks on colony staff, using A.U.E. vocabulary.

We should also mention here that Paragraph E of Part 2 of Art. 2073 of the CC (the new article on “fakes,” taking into account the hate motive in the sentence) was used in Krasnodar Krai for publishing information on Facebook “about the Russian armed forces' losses of military equipment and personnel” and criticizing the Russian military. According to the verdict, the convicted person “was motivated not only by political hatred, but also by national hatred – towards Chechens.” We cannot assess with confidence the lawfulness of this verdict.

Just like in 2021, we are not aware of any verdicts under Art. 2801 of the CC (calls for separatism). Remember that at the beginning of 2021, this article was partially decriminalized, a similar Article 20.3.2 of the Administrative Code was introduced, and criminal liability under Article 2801 occurs only a year after administrative prosecution.

In 2022, penalties for public statements, excluding wrongful convictions, were distributed as follows:

- 71 people were sentenced to imprisonment;

- 83 received suspended sentences without any additional measures;

- 57 were sentenced to various fines;

- 3 were sentenced to mandatory labor;

- 1 was sentenced to the restriction of liberty;

- 2 were sentenced to compulsory treatment;

- 3 – measures unknown.

The number of people sentenced to imprisonment was again higher than a year earlier: in 2021 we reported 62 prison sentences.

Most of them received prison terms in conjunction with charges other than statements. Eight were already serving prison time, and their terms were increased. Some were released on parole or were on probation.

However, eight people received prison terms in the absence of any of the above-mentioned circumstances that reduce the chances of avoiding incarceration (or, perhaps, in some cases, we just do not know about them). This is without taking into account the obviously wrongful convictions and without considering Article 2052 of the Criminal Code as “terrorist” (about it see below).

The most notable of them was the head of the unregistered organization People's Council of Kazan (probably one of the varieties of “citizens of the USSR”), 55-year-old Vadim Tyulyukov. He was sentenced under Article 280 of the CC to two and a half years in a penal colony with a ban on social activities and serving as a head of organizations for posting comments on VKontakte containing calls to attack government officials and law enforcement officers.

Civil activist Grigory Severin from Voronezh was sentenced under Part 2 Article 280 of the CC to two years in a penal colony and a two-year ban on administering websites for writing a comment on his VKontakte page saying “slash the GB” under a post about the shooting outside the Lubyanka FSB building in December 2019.

And whereas in these two cases the convicted engaged in at least some visible activity in their regions and potentially had a noticeable audience, we do not know about the others' affiliation with any associations.

In Simferopol, 29-year-old Yevgeny Sukhodolsky was sentenced under Article 280 of the CC to one and a half years in prison and a two-year ban on publishing information on the Internet for publishing a text “calling for violence against members of a particular ethnic group” in a messenger’s group chat.

In Krasnoyarsk Krai, a resident of Dzerzhinsky district was sentenced to one year in prison under Part 1 of Article 280 of the CC for calls to attack the country's leadership.

In Kazan, a local resident received two and a half years in jail under Part 2 of Article 280 of the CC for posting “calls to extremist activity” in a social network.

In Nizhny Novgorod, Alexei Felker was sentenced under Art. 3541 of the CC to six months in prison with a three-year ban on activities related to the administration of websites for publishing an image in a social network with a portrait of NSDAP chairman Adolf Hitler with the Eiffel Tower in the background and his own song, in which was detected “a combination of linguistic and psychological elements that indicate the author’s justification of the actions of Adolf Hitler, his associates (Goering and Goebbels), the SS, and the army... including during World War II.”

In Smolensk, Alexander Sokolov got two years in a penal colony with a three-year ban on online posting and a fine of 100,000 rubles under Article 3541 of the CC for his VKontakte posts “expressing clear disrespect for... George Zhukov, insulting the memory of soldiers of special units ...endorsing the activities of the collaborator Krasnov, .... who fought on the side of the Third Reich, and justifying the actions of collaborators who fought on the side of Nazi Germany (the Cossack formations of the SS troops).” During the trial he pleaded guilty in full, repented, and apologized to the veterans of the Great Patriotic War, but this did not save him from a prison sentence.

Neither did a public apology recorded on video save Igor Levchenko, singer from Krasnogorsk, Moscow region, who got three years in the penal colony under Paragraph A, Part 2 of Art. 282 of the CC (incitement of hatred with threat of violence) for publishing a video in Instagram on February 24 where he sang a song and made a statement that showed “signs of incitement of hatred and hostility towards Russian servicemen with threat of violence and committing murders.”

In all of these cases, we have not seen the publications, know nothing about the convicted and the context of their statements, and have no way of explaining the reasons for the harshness of the sentences.

Compared to the previous year, the situation remains almost unchanged: in 2021 we reported nine prison sentences, four in 2020, in 2015-2019 this number fluctuated, without any apparent pattern, between five and 16, and in 2013 and 2014 there were only two such convictions in each[17].

If we calculate the percentage, then in 2022 the share of incarceration sentences where we are unable to explain the severity represents 3.6% of the total number of convicts. We can't say that this figure has any stable dynamics: in 2021 it stood at 4.3%, in 2015-2020 it ranged from 2.8% to 6.8%, and in 2013 and 2014 it was just over 1%.

Prior to 2020, we did not perform any calculations with regards to Art. 2052 of the CC at all, since the penalties under the anti-terrorism article are traditionally more severe, and our knowledge of the specific content of cases is always too limited; additionally, until 2018, the vast majority of sentences under Art. 2052 had nothing to do with countering incitement to hatred. But the situation is changing, and the application of this article is expanding, so this is the third year that we are accounting separately for those punished with incarceration under this article. In 2022 we know of eight people convicted under Article 2052 alone, without the “aggravating circumstances” listed above. Another five were convicted under the combination of Art. 2052 and Art. 280 of the CC; we did not count them in the calculations above under Art. 280, so the total is 13. In 2021, we also reported 13 people, and eight in 2020.

The majority of such convictions that we are aware of involved statements directed not against ethnic or religious groups, but against the authorities. However, three of those convicted were engaged in radical Islamist propaganda. The Southern District Military Court sentenced Nozim Ikromzhon Ugli Rustamov to two years in a penal colony for posting on a social networking site a “video file containing calls to terrorist activity.” And the First Eastern District Military Court in Omsk sentenced three residents of a Central Asian state, two of whom were sentenced to imprisonment in a general-regime penal colony (two years and six months and two years, respectively) only under Part 1 of Art. 2052 of the CC for "advocating terrorism among their entourage and inducing people to travel to Syria.”

In the Altai Republic, a follower of the far-right organization Russian National Unity (RNE) was sentenced under this same article to two years in a general-regime penal colony with a one-and-a-half-year ban on publishing materials online for posting on VKontakte “media materials containing propaganda of the ideology of Nazism and racial superiority” and “publicly justifying actions of terrorists.” In particular, he posted a poem online dedicated to Timothy McVeigh, “which justifies the man who shot people on the basis of their ethnicity.”[18] In July 2022, this poem was added to the Federal List of Extremist Materials (entry 5292).

The sentence against a 56-year-old resident of Primorsky Krai was also related to a literary work: he received three years in a general-regime penal colony with a two-year ban on activities related to the posting of materials on the Internet for writing a “literary work” in late December 2020 that encourages others “to commit acts aimed at the violent overthrow and seizure of power in the Russian Federation” and for posting this work for free access on Proza.ru, VKontakte, and Facebook.

Civil activist Rodion Stukov was involved in protests in support of Navalny. The First Eastern District Military Court sentenced him to two years in a general-regime colony with a ban on Internet publications for two years for recording voice messages calling for the use of force against police officers at protest rallies in January 2021 and publishing them in a Telegram group with half a hundred participants.

In Kuzbass, the court sentenced a 41-year-old Prokopyevsk resident who, according to the prosecutor's office, “posted publications on the Internet that incited the murder of the President of the Russian Federation,” to a year and a half in prison and a ban on the administration of Internet sites.

The First Eastern District Military Court sentenced 42-year-old Sergei Zvonkov to two years in a penal colony; according to law enforcement officials, he “published posts on the Internet calling for the murder of top government officials by terrorist attack.”

Five people convicted under the combination of Articles 280 and 2052 of the CC were also sentenced to imprisonment for publications containing threats against government officials, including the President of the Russian Federation.

The Central District Military Court in Yekaterinburg sentenced an employee of the Izhevsk Mechanical Plant to nine years in prison for posting comments on VKontakte calling for murder of law enforcement officers.

Four more people were sentenced by the First Eastern District Military Court. A resident of the Jewish Autonomous Region was sentenced to three and a half years in a general-regime penal colony with a three-year ban on the right to engage in activities related to the public posting of materials on the Internet for publishing materials on a social network “containing public calls for the murder of state figures and members of a federal political party.” Alexei Skotnikov, a resident of the town of Osinniki in the Kemerovo region, was sentenced to two years in a penal colony and banned from posting materials online for two years for posting on VKontakte “calls for violent regime change and murder of government officials and law enforcement officers.” A resident of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky was sentenced to six years in a high-security penal colony with a two-year ban on publications on the Internet: according to the case file, he left comments on VKontakte three times calling for the murder of Putin, members of United Russia, and government officials. And a resident of Kemerovo was sentenced to a year and a half in a penal colony with a three-year ban on the use of the Internet for publishing on social networks calls “for extremist actions against the Chinese” and “justification of terrorism against security officials (siloviki) and government officials.”

In 2022, the share of suspended sentences decreased from 43.6% (in 2021) to 37.7% (83 out of 220). The share of the remaining convicts sentenced to punishments involving neither real nor suspended imprisonment, i.e. mainly fines, was 27.7%, which was slightly higher than the 25% in 2021.

Almost all of the sentences mentioned additional bans on activities related to the administration of Internet sites, bans on publications on the Internet, or on the use of the Internet in general. In three cases, confiscation of the “instruments of crime” (routers, laptops, cell phones) was reported.

As has become a tradition, the overwhelming majority of convictions were for material posted on the Internet – 184 out of 208, or 88.5% (91% the year before).

As far as we were able to understand from the reports of the verdicts, these materials were posted on:

- social networks – 142 (64 on VKontakte, 2 on Facebook; 8 on Instagram; 3 on Odnoklassniki; unspecified social networks – 65[19]);

- messengers – 13 (Telegram – 7, unspecified – 6);

- YouTube – 2;

- public chats – 2;

- online media – 2;

- unspecified online resources – 23.

The types of content are as follows (different types of content may have been posted in the same account or even on the same page):

- comments and remarks, correspondence in chats – 59,

- other texts – 36,

- poems – 2,

- calls in unclear forms – 6,

- instructions for making explosive devices – 5;

- videos – 36 (including 2 of one’s own attacks),

- images (drawings and photographs) – 13,

- audio (songs) – 7,

- administration of groups and communities – 2,

- unspecified – 38.

As for where materials are posted, that remains the same (see previous reports on this topic, as well as reports on online prosecutions for extremism[20]): Law enforcement still focus their monitoring on social networks; in the last three years, messengers have been added, but the percentage of cases involving them is still small. In terms of genre distribution, the trend we noted in 2020 has strengthened[21], – a significant increase in the proportion of sentences “for words” in the literal sense, that is, for textual statements, with comments and remarks prevailing; and the tendency to prosecute videos and other pictorial materials is diminishing[22].

The number of convictions for offline statements turned out to be one-third higher than a year earlier: 24 convictions for 31 people, compared with 17 for 19 people in 2021. They were distributed as follows:

- agitation in prisons, colonies, and treatment and correctional facilities – 13 (1 person – shouts from the window, 1 – colony wall newspaper, others – agitation in the cell among other prisoners);

- shouts during attacks – 1;

- shouts inside an MFC (multi-functional center for public services) building – 1;

- shouts in the street – 1;

- speech at a rally – 2 sentences (4 people);

- speech at meetings of like-minded people (“citizens of the USSR”) – 1;

- leaflets – 2 sentences (6 people);

- graffiti – 3 sentences (4 people).

The percentage of people convicted of agitation in prison has decreased compared to 2021. Remember[23] that we find these verdicts questionable. It is true that there is a significant proportion of people who are prone to violence among prisoners, so radical agitation in this environment is always dangerous. But the key criterion of the size of the audience remains unclear in cases of public statements: for example, it is unlikely that a conversation in a narrow circle of cellmates can be considered public.

We are inclined to consider sentences for speeches at a rally, shouting during an attack, or even simply street agitation (verbal or by handing out leaflets) as legitimate by the same criterion. But the need to prosecute specifically for singular graffiti on fences and buildings raises serious doubts. The principle by which the authorities prosecute such offenses administratively or criminally remains unclear to us.

We often do not have access to the materials that became the subject of legal proceedings, so as far as the content of statements is concerned, in many cases we are forced to focus on the descriptions of prosecutors, investigative committees or the media, although these descriptions, unfortunately, are not always accurate, and in some cases they simply do not exist. Therefore, we can conduct an analysis of the direction of incriminated statements only for a portion of the cases we are aware of.

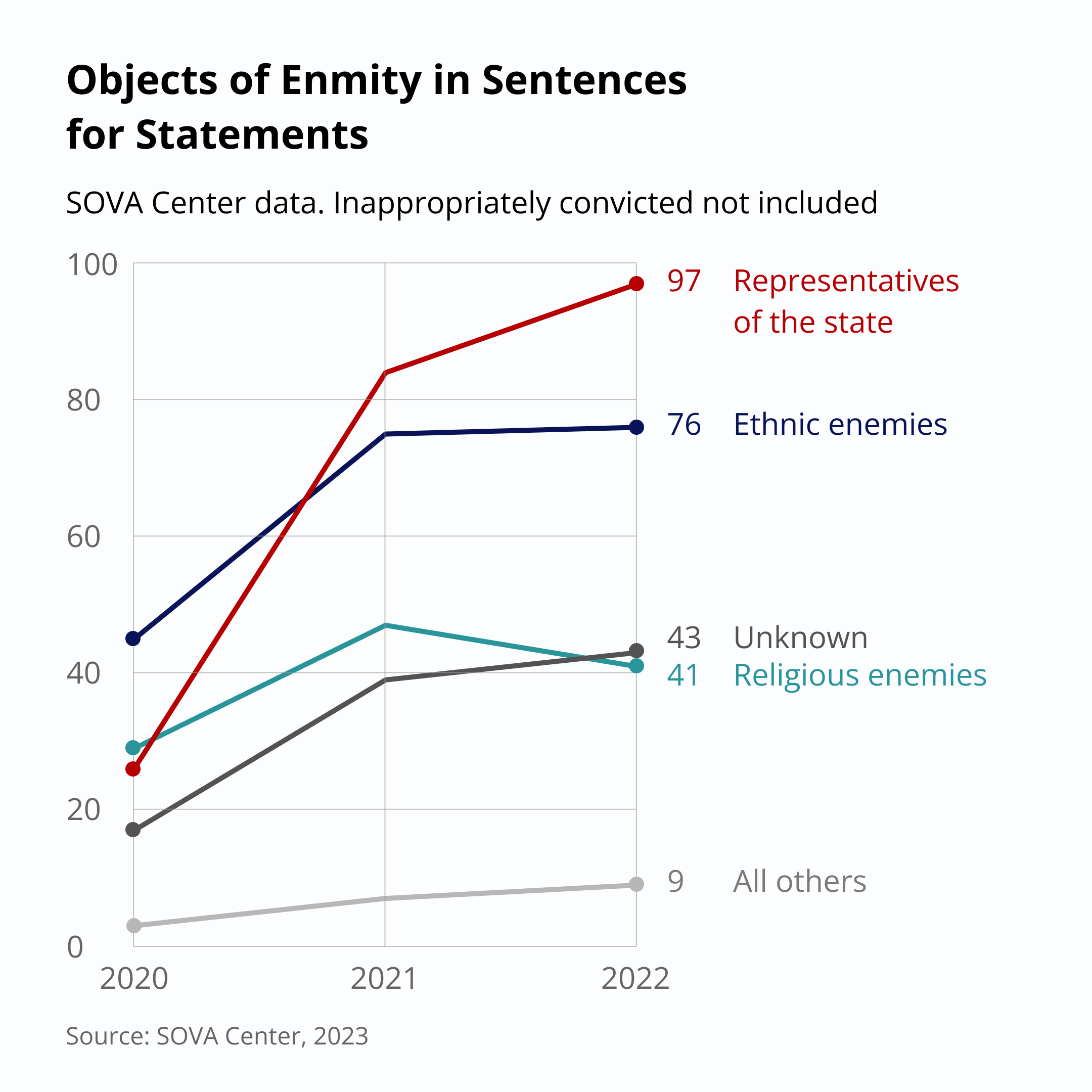

We identified the following targets of hostility in the sentences passed in 2022 (the incriminated materials expressed hostility toward more than one group):

- ethnic enemies – 76, including: Jews – 17, natives of Central Asia – 11, natives of the Caucasus – 13, Mongols – 1, Chinese – 1, Sinti and Roma – 2, Russians – 5 (including in connection with military actions in Ukraine), dark-skinned people – 2, non-Slavs in general – 11, unspecified ethnic enemies – 13;

- representatives of the state – 97, including: government employees in general – 34, members of the United Russia party – 5, FSB personnel – 6, officials of the Ministry of Internal Affairs – 1, military – 9, police and security forces (siloviki) – 29, President of the Russian Federation – 9, Samara regional government – 1, prison staff and their family members – 2, custody officials – 1;

- Belarusian security forces (siloviki) – 1;

- religious enemies – 41, including Orthodox Christians, including priests – 5, Muslims – 13, infidels from the Islamic point of view (romanticizing militants, calls to join ISIS and jihad) – 21, unspecified religious enemies – 2;

- veterans – 4;

- communists – 1;

- women – 1;

- people who drink alcohol – 1;

- homeless – 1;

- unknown – 43.

The situation of 2021 repeats itself: the three main groups of enemies – ethnic, religious and state representatives – remain the same. In 2022, as in the year before, state officials prevail, they are mentioned in 46% of sentences (41% in 2021), and their share continues to increase, albeit more slowly, at the expense of those of ethnic and especially religious enemies.

In contrast to the previous year, the number of sentences for offline political hostility went up to reach nine (we reported one in 2021) and almost equaled the 10 sentences for ethnic xenophobia.

For Participation in Extremist and Terrorist Groups and Banned Organizations

In 2022, we have information about 44 verdicts against 78 offenders under articles 2821 (organizing, recruiting or participating in an extremist community), 2822 (the same for a banned extremist organization), 2054 (the same for a terrorist community, excluding recruitment), 2055 (the same for a banned terrorist organization), and 2823 of the CC (financing of extremist activities). That's twice as many as in 2021 (22 convictions against 32 people). These numbers do not include inappropriate convictions, whose number in the past year was again much higher than in other categories: we have deemed unlawful 86 sentences against 186 people[24] (all the convictions under Art. 2823 known to us were unlawful). According to the Supreme Court data[25], 155 people were convicted under the same articles, if we count only the main charge, in the first half of 2022 alone (233 in the whole of 2021). Thus, assuming that such sentencing continued with the same intensity in the second half of the year as in the first half, the number of convicts in this category increased by almost a third.

We know that in 2022, Article 2821 of the Criminal Code was used in 12 convictions against 34 people.

Traditionally, it was primarily applied to members of ultra-right groups.

In Perm, the leader and participants of the National Revival Path of Russian Patriotism (NVSRP) group, Andrey Ageyev, Sergei Igitov, and Daniil Zorin were sentenced to suspended sentences with a ban on creating and administering websites and communities in social networks for participation in an extremist community; according to investigators, they were preparing attacks on police officers, people of “non-Slavic appearance,” and LGBT people, conducted training sessions in the woods, and discussed how to obtain weapons. During searches, traumatic pistols and bullets, cold weapons, books with “extremist content,” and nationalist paraphernalia were found and confiscated.[26]

In the Bryansk region, another member of that group was sentenced to two years of penal colony under Part 1, Art. 2821 of the CC (organizing or leading an extremist community). In February 2019, he created an ultra-right community on a social network, posted nationalist materials there, and looked for like-minded people. He also distributed propaganda leaflets calling to join the NVSRP and was detained while handing out leaflets in Bryansk.

In Krasnodar, a court sentenced members of a group called the United Russian National Party (ERNP) – six residents of Gelendzhik, five of whom were minors. ERNP members “disseminated ideas ... about the supremacy of the Slavic peoples in Russia, about the restriction of the rights of representatives of other ethnicities,” and also advocated for “‘cleansing’ society of people who abuse alcohol, use and distribute drugs... of representatives of informal subcultures and non-traditional sexual orientations.” Group leader Bogdan Laskin together with Evgeny Talykov conducted hand-to-hand combat training in Gelendzhik among other ERNP members. The participants used an emblem “similar in appearance to the emblem of the troops of Nazi Germany.” They painted this emblem and similar images and inscriptions on city buildings and posted flyers. In April 2020, members of the group burned a copy of the Victory Banner in a bonfire and distributed a video of it in a messenger group. Between December 2019 and March 2021 in Gelendzhik, ERNP members attacked people who were deemed to be “leading asocial lifestyles” and “members of informal subcultures.” Bogdan Laskin was sentenced under Part 1 of Article 2821 in combination with Article 3541 and Part 4 of Article 150 of the Criminal Code (involvement of minors in a criminal group and the commission of crimes motivated by political, ideological, racial, national hatred and enmity towards any social group) to six and a half years in a general-regime penal colony, with a two-year ban on the use of the Internet, with a year-and-a-half restriction of freedom. The other defendants were found guilty under Part 2 of Art. 2821 of the CC (participation in a group), and two of them were also found guilty under Art. 3541 of the CC and sentenced to two to three years' suspended imprisonment, with deprivation of the right to engage in activities related to the administration of sites and channels on the Internet for two years. It is unknown why the articles of the Criminal Code for violent attacks were not imputed in the verdict.

Separately, a sentence was handed down to Yevgeny Talykov, a member of the ERNP. The Novorossiysk garrison court sentenced him to six years in a general-regime penal colony under Part 2, Art. 2821, Art. 3541 and Art. 150 of the CC.

These two groups (NVSRP and ERNP) were mentioned a year earlier in connection with the mass detentions of members of the youth radical community M.K.U. (see below).

In Astrakhan, the leader and members of the Astrakhan National Movement group, aged between 17 and 21, were convicted of committing “several acts of ideological vandalism” and “distributing propaganda materials on social networks.” Depending on their roles, they were found guilty under Part 1 of Article 2821 of the Criminal Code, Part. 1.1. of Art. 2821 of the Criminal Code (inducement, recruitment to the activities of an extremist community), as well as under the articles for violence and vandalism.[27] The group leader received seven years in a general-regime penal colony, while the others got suspended sentences.

Three members of the neo-Nazi group White City 31 were convicted in Belgorod Oblast; according to media reports, they had already committed over 30 hate-motivated attacks in two years.[28] The court sentenced David Tronenko to 12 years in prison under Parts 1 and 1.1 of Article 2821 and under articles for violence and vandalism. The other two (one of whom was a minor) were sentenced under Part 2 of Article 2821 and the articles on battery to four and three years in prison, nine months of corrective labor, and, in addition, a ban on running groups in social networks.

In Omsk, a "citizen of the USSR,” chairman of the “Omsk Regional Executive Committee of the Council of People's Deputies of the RSFSR,”[29] Vladimir Beskhlebny, 72, received a suspended sentence “for preparing to form an extremist community” with “the goal of ousting the Omsk regional government and arresting the Governor on June 24, 2020, the day of the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the Victory Day. … He searched for contacts of former and active servicemen, found out the location of arms and ammunition depots in the region, and planned an armed takeover of the TV center…”

In Khabarovsk, an 18-year-old young man was sentenced under Articles 2821, 2051, 2052, 280, and 163 (with application of Art. 30, attempted extortion) to eight years in a general-regime penal colony, and his 17-year-old girlfriend was fined under articles 2821, 30, and 163 of the CC. The young man, according to law enforcement officials, distributed literature prohibited in Russia, drew symbols “similar to Nazi symbols” on houses in Khabarovsk, printed leaflets, and made incendiary devices. He was also going to carry out attacks on “non-Russians.” In addition, he intended to commit “several terrorist acts involving the arson of a number of buildings,” and also wanted to extort money “from wealthy citizens in order to obtain funds to finance the activities of the extremist community.” In particular, these two were planning extortion with a threat to set a car on fire, but were detained by the FSB.

In the Bryansk region, a 19-year-old local resident was sentenced to a fine under Part 1 of Art. 2821 of the Criminal Code (with application of Part 3 of Article 30 of the Criminal Code). According to the court, he “made a plan to create an extremist community” with the purpose of attacking and robbing “non-Slavs” and drug sellers, and engaged in “search, indoctrination, and recruitment” of supporters. But he “recruited” FSB operatives, who detained him.

In Kabardino-Balkaria, 11 residents of the village of Anzorey were convicted under Article 2821. According to the investigation, guided by Sharia law, they formed “religious patrols,” intimidating and beating those who did not share their views. Five episodes between 2016 and June 2020 were reported in the case file: two cases involved beatings, and three involved threats. All those convicted, including community leader Sultan Atalikov, received suspended sentences[30].

And the last conviction under this article that we are aware of is related to Ukraine. The First Eastern District Military Court sentenced a resident of Norilsk to nine years in a high-security penal colony under Part 1.1 of Art. 2821 and Part 1.1 of Art. 2051 of the CC. According to the investigation, while in pre-trial detention, he engaged in persuading his fellow inmates to join the Ukrainian far-right organization Pravyi Sector, banned in Russia, take part in fighting in eastern Ukraine, and organize prison bombings in Bryansk, etc.

According to our data, Article 2822 of the CC was applied in 22 verdicts against 27 people.

This article was actively used to prosecute members of the banned “citizens of the USSR” organizations. Seven people were convicted, starting with Sergei Taraskin, the leader of the Union of Slavic Forces of Russia (abbreviated as SSSR, Russian for USSR), who publicly referred to himself as “the acting president of the USSR,” and sometimes even as “the emperor of the Russian Empire.” A court in Moscow sentenced him to eight years in a general-regime penal colony.

In Primorskiy Kray, a “citizen of the USSR” was sentenced to seven years in prison and a year and a half of restriction of freedom, not only under Part 2 of Art. 2822, but also under Part 1.1 of Art. 2822 (recruitment to an extremist organization) and Part 1 of Art. 2051 of the CC (facilitation of terrorist activities). Terrorist activity here was understood to mean the alleged overthrow of the constitutional order.

Additionally, “citizens of the USSR” from Ufa, Maykop, Orenburg, and Belokurikha (Altai Krai) were charged and found guilty of publishing materials of the SSSR organization on VKontakte and of distributing leaflets. Three received suspended sentences. Two “citizens of the USSR” from Orenburg were sentenced to corrective labor.

Since 2018, various associations of “citizens of the USSR” have been appearing in criminal summaries more and more frequently. It seems that for law enforcement agencies they have taken the place of the activists of the “Spiritual-Ancestral Power Rus,” previously mentioned almost annually in our reports; activity of these two organizations are formally similar in many ways.

However, Art. 2822 was used against other organizations as well. Five people were convicted of belonging to Pravyi Sector in Stavropol Krai and Moscow. Some of them were accused of intending to travel to Ukraine to join Pravyi Sector, some of recruiting for the organization, and some of creating propaganda videos and planning terrorist attacks. All of them were sentenced to long prison terms.

Four people in Rostov-on-Don and one in Neftekamsk (Bashkortostan) were sentenced to prison for involvement in the radical Islamist organization Takfir wal-Hijra. Although the organization by that name has long ceased to exist, there have indeed been and probably are followers of some of its ideas in Russia; we are unable to assess the extent of their radicalism and the content of their actual activities.

10 people in the Moscow, Irkutsk, and Samara regions and the Republics of Adygea and Komi were found guilty of participating in the criminal subculture A.U.E., which for some reason is recognized as an extremist organization[31]. The vast majority of them had already been in prison, and had to serve additional prison time. Only one 20-year-old resident of Maikop received a suspended sentence.

In 2022, we know of two convictions against four people under Article 2054 of the CC. Two people from Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk were sentenced to prison for participating in the Sakhalin Tactical Club of Nationalists (S.T.C.N.) terrorist community, possessing weapons and explosives, and undergoing training to commit a terrorist attack. Two other people in Rostov-on-Don were convicted of involvement in ISIS activities. In addition to Article 2054, a number of other anti-terrorism articles were included in the sentences, and collectively all of the convicts were sentenced to long prison terms.

We are aware of nine convictions against 14 people under Article 2055. All the cases involved radical Islamists. We are talking about involvement in such organizations as the Islamic State and Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham. All were sentenced to imprisonment in combination with other anti-terrorism articles.

Federal List of Extremist Materials

In 2022 the process of expanding the Federal List of Extremist Materials continued to slow down: the list was updated 23 times with 81 entries (110 a year earlier). Thus, the number of entries on the list has reached 5,334[32].

New entries fall into the following categories:

- xenophobic materials of contemporary Russian nationalists – 44;

- materials of other nationalists – 5;

- materials of Orthodox fundamentalists – 1;

- radical anti-Christian materials – 2;

- materials of Islamic militants and other calls for violence by political Islamists – 2;

- materials of Hizb ut-Tahrir – 1;

- other Islamic materials – 3;

- materials by other peaceful worshippers (writings of Jehovah's Witnesses) – 1;

- materials from the Ukrainian media and the Internet – 1;

- anti-government materials inciting to riots and violence – 14;

- works by classical fascist and neo-fascist authors – 2;

- parody banned as serious materials – 1;

- A.U.E. materials – 1;

- people-haters’ materials – 1;

- citizens of USSR materials – 2.

As in previous years, the overwhelming majority of the new entries are materials by Russian nationalists; the number of entries added containing such materials has not decreased much compared to the previous year. At least 65 of the new 81 entries are online materials: video and audio clips, articles and other texts, and various images. In addition to online publications and posts on social networks, materials published in Telegram channels were added to the list (materials from the Telegram channels of the 1ADAT community and M.K.U.). Offline materials include books by Russian and other nationalists, classics of the Third Reich, and Salafist Muslims. However, with regard to songs or videos, it is often difficult to understand where the banned materials were published: the entry contains only the title and sometimes the first and last lines.

Of course, the list has been updated less intensively, but it has grown so large that it is impossible to make sense of it. The entries are still being described in a manner that makes it hard to understand, which causes a lot of difficulties in interpreting the material. This is not to mention the rules of bibliography, which in all the years of the existence of the list have never been taken into account.

And, as usual, some of the newly added materials were declared extremist clearly unlawfully and inappropriately: these are mainly translations of Islamic treatises, including medieval ones. However, the number of unlawfully banned materials was significantly lower than the year before (eight in 2022 compared to 19 in 2021).[33]

Banning Organizations as Extremist

Lists of extremist and terrorist organizations were expanded more intensively than the year before.

In 2022, 13 organizations were added to the Federal List of Extremist Organizations, published on the website of the Ministry of Justice (a year earlier there were nine).

Russian nationalist organizations of varying degrees of activity and prominence joined the list.

Male State was declared extremist by the Nizhny Novgorod regional court on October 18, 2021. The MG, founded in 2016 by Vladislav Pozdnyakov, positions its ideology as “national patriarchy,” advocates “racial purity,” and not only insists that women's behavior should be dictated by ultraconservative values, but also advocates extremely radical misogynistic ideas and appeals. MG supporters have repeatedly harassed and threatened female journalists and activists online, and in August and September 2021 harassed chain restaurants for ads featuring young black men[34].

The Nevograd group was declared extremist by the St. Petersburg City Court on October 25, 2021. The court decision also listed the group’s alternative names: Nevagrad, Nevograd-2, BTO-Nevograd, First Line Nevograd, Nevograd first line, Nevograd First Line in Russian transcription, and FirstLineNevograd. Judging by this list, the name Nevograd refers to several St. Petersburg neo-Nazi groups associated in one way or another with Andrei Link (Kleschin, Ivanov)[35].

The ultra-right organization NORD (People’s Union of Russian Movement) was declared extremist by the Pervomaisky district court of Omsk on April 19, 2022. This group, comprising about 20 residents of Omsk and about 60 followers from other regions, was founded by two 20-year-old Omsk residents, Kirill Vasyutin and Dmitry Lobov. Criminal proceedings were initiated against them under Part 1 Art. 2821 of the CC. NORD members “promoted hatred toward people of other ideologies and called for violence... and prepared attacks on people of non-Slavic appearance, natives of Central Asia and the Caucasus, anti-fascists, and LGBT.” We have information about one attack perpetrated by the group and motivated by ethnic hatred and about the conviction of one of its members under Part 2 of Art. 282 of the CC.

The far-right community Project Sturm was declared extremist by the Leninsky District Court of Perm on June 14, 2022. The group emerged in December 2018 (its social network page gives a different date – March 15, 2019), founded by Daniil Vasilyev. The group members numbered about 15 people, many of whom had previously attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies. The leader of the group became one of the defendants in the case of Putin's mannequin tied to a pole[36] and in August 2020 was given one year of suspended sentence under Part 2 of Art. 213 of the Criminal Code (hooliganism). Several group participants were convicted under Articles 20.3 and 20.29 of the CAO. In the fall of 2021, members of Project Sturm were detained as part of the investigation into the September 20 shooting organized by Timur Bekmansurov at Perm State National Research University. Vasilyev had left Russia shortly before and sought political asylum in Austria. One of the group members confessed, mentioning that Vasilyev posted “an archive with extremist literature” and materials describing methods of conspiracy, “methods of direct action, attacks on drug addicts, alcoholics, and citizens of non-Russian nationalities” to the Sturm group chat. In addition, three Sturm activists planned an attack against an immigrant who worked at a shawarma stand.

Two organizations of “citizens of the USSR” were also added to the list.[37] The first is the Public Association “People's Council of Citizens of the RSFSR of the Arkhangelsk Region,” recognized as extremist by the Arkhangelsk Regional Court on May 24, 2022.[38] The second – the Interregional Public Organization “Citizens of the USSR”[39] – was declared extremist by the Samara regional court on June 16, 2022. The organization in question is known as “Novokuybyshevtsy.”[40]

In addition, the list now includes three Ukrainian far-right organizations: Sich-C14 (Hromadska organizatsiya Sich-C14, other names Slava i Chest (Glory and Honor), GO C14, Osnova Majbutnogo [The Foundation of the Future]), Volunteer Movement of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), and Chornij Komitet (Black Committee), recognized as extremist by the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation on September 8, 2022.[41]

Finally, the list was expanded to include the People's Movement Adat, which was declared extremist by the Chechen Supreme Court on May 12, 2022. This movement of Islamic separatists, which opposes Kadyrov’s regime, is represented by the 1ADAT Telegram channel. It heroizes all the Chechen uprisings against the Russian authorities, but as far as we know, does not carry out any armed struggle itself. The lack of information prevents us from making a substantive judgment on the appropriateness of this ban.

On March 21, 2022, Tverskoy district court of Moscow made an unprecedented decision, recognizing as extremist the activity of Meta Platforms Inc. related to sales of its products Facebook and Instagram (it was specified that this decision did not apply to the activity of WhatsApp messenger also owned by Meta due to its lack of functions for public distribution of information). Thus, Meta was included in the list of banned organizations, albeit not in its entirety, but only in some part of its activities. We consider this decision not only strange in form, but also unlawful.

We also consider unlawful the June 10, 2022 decision of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Tatarstan recognizing the Tatarstan Regional All-Tatar Public Movement, or the All-Tatar Public Center, as extremist.[42]

Thus, as of February 22, 2023 the list included 101 organizations[43], the activity of which is prohibited by court and their continuation is punishable under Art. 2822 of the CC.

In December, the organization Vesna[44] was recognized as extremist, but the decision has not yet come into force. We are not aware of any other bans on organizations in the past year.

The list of terrorist organizations published on the website of the FSB was updated in 2022 with seven organizations (three in 2021)[45].

Three of them are Islamist: Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (decision of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of September 14, 2022), Khatlon Jamaat (decision of the Second Western District Military Court of November 3, 2021; apparently this refers to one of the existing Tablighi Jamaat associations in Tajikistan), and the Kushkul Muslim religious group (suburb of Orenburg; decision of the Orenburg Regional Court of March 4, 2022[46]).

The Ukrainian Azov Battalion was declared terrorist by the Russian Supreme Court on August 2, 2022. The Noman Çelebicihan Crimean Tatar volunteer battalion was declared terrorist by the Russian Supreme Court on June 1, 2022. The battalion was formed in January 2016 with the support of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, banned in Russia as an extremist organization.

The left-wing anarchist movement Narodnaya Samooborona (People's Self-Defense) was declared terrorist by a decision of the Chelyabinsk Regional Court on September 12, 2022.

Finally, on February 2, 2022, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation declared terrorist the International Youth Movement Columbine (“Skulshuting” [Schoolshooting]), although there is no such movement, but rather a youth fashion trend or subculture having no ideological or political nature.

Additionally, as early as January 2023, the Supreme Court recognized as terrorist Maniacs the Cult of Murderers (M.K.U.; other names include Maniacs Cult of Murders, Youth that Smiles [abbreviates as M.K.U.]), already mentioned several times in this report.

M.K.U. was formed in 2017 by Yegor Krasnov, a neo-Nazi from Dnieper, and operated in Russia and Ukraine. Followers of this network organization embraced the ideology of people-hating, whose elements have been widespread in the neo-Nazi movement at least for the past decade and a half. Mass detentions of M.K.U. supporters in various regions of the country were reported by FSB and police officers beginning in February 2021, then throughout 2022, and continue to be reported in 2023.

In 2021 and 2022, Sova Center received several emails with links to videos capturing scenes of attacks on migrants and homeless people signed by M.K.U., reports of alleged terrorist attacks, and threats to employees.

In February 2022, the Basmanny Court in Moscow arrested Ukrainian citizen Yegor Krasnov in absentia on murder charges. Krasnov himself appears to have been detained in a pre-trial detention facility in the city of Dnepr for a long time.

In 2022, the leader of the Belaya Ukhta movement in Komi and a follower of M.K.U. from Zabaikalye were convicted in cases directly connected to M.K.U. (both mentioned above). In addition, members of other groups, mentioned in the Interior Ministry reports in connection with the detentions in the M.K.U. case, whose links to M.K.U. are unclear to us, were convicted: in Perm and Bryansk, those were members of the NVSRP group, and in Krasnodar and Novorossiysk, members of the ERNP group (also mentioned above).

Judging by the scale of the detentions, this is far from the end of the great “M.K.U. case,” and there may be trials ahead for participation in the M.K.U. as a terrorist organization (the M.K.U. was not yet listed at the time of publication of the report).

Prosecution for Administrative Offences

In this section, we refer to several articles of the Administrative Code as “anti-extremist”: 20.3 (display of prohibited symbols), 20.29 (distribution of prohibited materials), 20.3.1 (incitement to hatred), 20.3.2 (separatism), as well as Articles 20.3.3 (discrediting the military and government officials abroad) and 20.3.4 (calls for sanctions against Russia), introduced in 2022, but we categorize the latter articles as entirely unlawful.[47] And the data provided in this report excludes unlawful decisions.

In the past year, thanks to cooperation with OVD-info, we have devised a better method of finding decisions on the Administrative Offenses Code on the courts' websites, which could not but affect the effectiveness of our data collection. Now we have information about 20% of the actual judgments, with the exception of the unlawful ones. This is not much, but this is significantly higher than before; so we cannot compare our own data for 2022 with previous years. But according to the Supreme Court, if we assume that the enforcement in the second half of the year was the same as in the first half, there was an increase, even without taking into account the new articles – and the number of decisions on “defamation” can be as much as half of the total amount of administrative anti-extremism enforcement.

According to SOVA Center, in 2022 302 decisions were made under Article 20.3.1 of the COA (at least one person was prosecuted four times, another five times, two more were prosecuted twice, and two decisions concerned minors).

The vast majority were punished for publishing on social networks, mainly on VKontakte, but the cases also included Odnoklassniki, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Telegram, WhatsApp (messages in a large group), and YouTube.

Incriminating comments, remarks, videos, and images on the object of hostility referred to:

- ethnic “others” – 332 (including the natives of Central Asia – 52, natives of the Caucasus – 60, Jews – 21, dark-skinned people – 6, Sinti and Roma – 6, Russians – 33, Ukrainians – 10, Tatar – 3, Yakut – 6, Chuvash – 1, Buryats – 2, Arabs – 1, Chinese – 1, Mongols – 2, Kazakh – 1, non-Russians in general – 10; unspecified ethnic enemies – 117);

- religious “others” – 26 (Orthodox Christians – 5, Jews – 2, Muslim– 8, infidels from the Islamic point of view – 6, Buddhists – 1; unspecified religious enemies – 4);

- representatives of the state – 65 (police – 25, military – 3; representatives of the authorities, including officials, deputies of the State Duma, and the President of the Russian Federation, – 33, FSB personnel – 2, traffic police officers – 1; bailiffs – 1);

- LGBT – 3;

- people of a “certain sex” (unclear which one) – 1;

- women – 2;

- children – 1.

Thus, in contrast to criminal law enforcement, the vast majority of punishments were for ethnic xenophobia, but not for political or ideological ones. There were even fewer punishments for religious xenophobia.

Only nine people were punished for offline acts. These were xenophobic statements during an on-site inspection of a land plot, in the presence of officials and neighbors on nearby plots; xenophobic insults targeting a cashier clerk in a store (two cases), a bus driver, a black female passenger on a bus; xenophobic speech at a people's meeting, shouts during a fight, shouts targeting non-Russians in the city center, and anti-religious and xenophobic shouts in the street by a man who called himself a Buddhist priest[48].

Most of those charged under this article were fined between 5000 and 20000 rubles. Eighteen people were arrested for periods between one and 15 days. Among the arrested was Edem Dudakov, a delegate of the Qurultay of the Crimean Tatar People and the former head of the State Committee for Nationalities and Deported Citizens of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, arrested for publishing a Facebook post about “militant vatniks,” in which experts saw linguistic and psychological signs of “inciting hatred and hostility toward Russians.” Eleven people were sentenced to compulsory labor. For example, Nikita Ustyuzhanin from St. Petersburg received seven days of arrest and 50 hours of compulsory labor simultaneously for insulting[49] a black girl Stella Kaziyake on the bus.

For the year 2022, we know of 496 cases of prosecution under Article 20.3 of the CAO. Of these, one person was charged 15 times, one 11 times, one 10 times, and three were charged twice each; at least four were minors. At least four people were concurrently punished under Article 5.35 of the CAO (failure by parents or other legal representatives of minors to fulfill their responsibilities to maintain and bring up minors). Presenting statistics on the application of the CAO for the first half of the year 2022, the Supreme Court combined Articles 20.3 and 20.3.1 of the CAO in groups for some reason; the total number of punishments amounted to 2,690. Extrapolating the numbers of the first half of the year to the entire year, we get an increase in the number of punishments under the two articles cumulatively by 31% compared to 2021. Based on the 2021 data, Art. 20.3 accounts for approximately three-quarters of the total.

Most of those punished under Art. 20.3 that we know of posted images of Nazi symbols (mostly swastikas) and runes on social networks, and in several cases, symbols of banned organizations such as ISIS, the Caucasus Emirate, Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Misanthropic division, and Pravyi Sector were posted. This was done mainly on VKontakte, but also on Odnoklassniki and Instagram, in Telegram, and in a WhatsApp group.

203 people were punished for offline acts.

In the year 2022, we know of 147 cases of punishment for displaying one's own tattoos with Nazi symbols. 58 of the prosecuted were prisoners in penal colonies (in addition, five prisoners had not tattoos, but other items with Nazi symbols – notebooks, clothes, rosaries), while the rest displayed their tattoos beyond prison walls.

In addition, 11 persons did a Nazi salute or shouted “Sieg Heil!” in public places (including on May 9), 11 persons were punished for graffiti and stickers with Nazi symbols on the facades of residential buildings in the streets, 12 persons displayed Nazi symbols on their clothes (including one who wandered around town in a Third Reich tunic), four people displayed Nazi symbols on the windows of their homes and in their dorm rooms; 10 people attached Nazi symbols to their vehicles (including a motorcycle and electric scooter); and three people (the director of an alcohol store, the manager of an anime store, and a bookseller) were punished for selling objects displaying Nazi symbols.

Most offenders under Art. 20.3 were fined between 1000 and 3000 rubles. 103 people were sentenced to administrative arrests (between three and 15 days). Among those arrested was Alexander Rybkin, a Moscow National Bolshevik, punished for a photo of his in VKontakte, which shows a tattoo of the rune Algiz, used by neo-Nazis (National Bolshevik claimed that the tattoo is one of the logos of the British neo-folk band Death in June).[50]

In at least six cases, the objects of the administrative offenses (caps, T-shirts, rosaries, scarves, and a bottle of vodka) were reported confiscated.

In 2022, we know of 168 decisions under Article 20.29 of the CAO; at least two of the punished were minors. According to the statistics of the Supreme Court, in the first half of 2022 penalties under Article 20.29 of the CAO were imposed 507 times on 507 individuals (501 individuals and six officials) compared to 764 in the first half of 2021. This is the second year in a row that the decrease in the number of those punished under this article has been observed.

Most of them paid fines of between 1000 and 3000 rubles. We know of five people who were sentenced to administrative arrests.

In the vast majority of cases, offenders were punished for publishing nationalist materials on VKontakte, such as 88 Precepts by David Lane, the slogan Russia for Russians, songs by musical groups popular with neo-Nazis (Kolovrat, Grot, Banda Moskvy, Korrozia Metalla, etc.); the neo-Pagan film Games of the Gods, The Anarchist's Cookbook, and radical Islamist materials, including songs by armed Chechen resistance singer-songwriter Timur Mutsurayev.

At least eight people were prosecuted under Art. 20.3 and 20.29 of the CAO simultaneously in 2022; 12 people were prosecuted under Articles 20.3 and 20.3.1 of the CAO simultaneously; two people under Articles 20.29 and 20.3.1 of the CAO simultaneously; and two people – under all three articles. All of them were fined.

When publishing data for the first half of 2022, the Supreme Court combined the data on Article 20.3.2 and the new Article 20.3.4 of the CAO. Judging by the combined data, punishments under these articles were imposed a total of 32 times (the 2021 statistics did not include Art. 20.3.2, and Art. 20.3.4 was introduced to the CAO in 2022), but it is likely that there was a technical error[51] in collecting data on the website of the Supreme Court and there were far fewer such decisions. We consider all of the verdicts under both Art. 20.3.2 and Art. 20.3.4 unlawful.

We have written in this report about the 966 decisions which we have no reason to consider unlawful. However, excluding the new articles of the CAO that we consider unlawful in general, we have to add that we are aware of 65 more cases of unlawful punishment under Article 20.3.1, 120 – under Article 20.3, 94 – under Article 20.29, 3 – under Article 20.3.2, with a total of 282 decisions. Thus, the proportion of unlawful decisions on the same set of articles of the Code of Administrative Offences slightly decreased compared to the previous year (158 unlawful vs. 466): in 2021, it was 25.3%, and in 2022, it stands at 22.6%.

[1] Yudina N. The Old and the New Names in the Reports. Hate Crimes and Countermeasures to Them in Russia in 2022 // SOVA Center. 2023. 30 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2023/01/d47028/) (further: Yudina N. The Old and the New…).

[2] Kravchenko Maria. Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremism Legislation in Russia in 2022 // SOVA Center. 2023. 2 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/publications/2023/03/d47794/) (further: Kravchenko М. Inappropriate Enforcement…).

[3] Counter-terrorism and extremism statistics for 2022 published // SOVA Center. 2023. 31 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/1/d47565/).

[4] According to the Criminal Code, extremist crimes are crimes committed with a hate motive, as defined in Art. 63 of the CC. The list of offenses classified as “extremist” in the CC is currently established by directive of the Prosecutor General's Office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. See: What constitutes an “extremist crime” // SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/directory/2010/06/d19018/).

[5] But such cases of improper enforcement are known and are described in: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[6] Data as of 22 February 2023.

[7] Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[8] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2022 // Website of the Judicial Department at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (http://cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=5895).

[9] In terms of which articles of the Criminal Code were used most frequently, Art. 280 was the winner: in the first half of 2022, 161 people were charged. It is followed by Art. 2052 (126 people), Art. 282 (22), Art. 3541 – (14). Part 1 Art. 148 – 6 people. Articles 2801, 2802, 2803, 2804, 2824 were not used.

For more information see: Official statistics of the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court on the fight against extremism for the first half of 2022 // SOVA Center. 2022. 15 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/10/d47063/).

[10] Consolidated statistics on the activity of federal courts of general jurisdiction and magistrate courts for the first half of 2021 // Official website of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. (http://cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=5895).

[11] Prior to 2018, convictions for statements were divided into “inappropriate” and “all other”.

[12] Text included in: The Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence // UN. 2013. 13 January (https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Opinion/SeminarRabat/Rabat_draft_outcome.pdf).

[13] The Supreme Court recognized the M.K.U. as a terrorist organization // SOVA Center. 2023. 16 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/01/d47493/).

[14] These sentences were therefore also mentioned in the analysis of sentences for hate crimes. Yudina N. The Old and the New…

[15] All of the numbers below are based on the sentences that we know about. But with the available volume of data, we can assume that the observed patterns and proportions will be approximately the same for the entire volume of sentences.

[16] On the “citizens of the USSR,” see: Akhmetyev Mikhail. Citizens without the USSR. Communities of “Soviet citizens” in modern Russia. Moscow: SOVA Center, 2022.

[17] Yudina N. Anti-extremism in Quarantine: The State against the Incitement of Hatred and the Political Participation of Nationalists in Russia in 2020 // SOVA Center. 2021. 4 March.

[18] In reality, McVeigh did not shoot, but set off a powerful explosion, and acted not “on a basis of nationality,” but attacked a building that contained government offices.

[19] Very likely, mostly on VKontakte.

[20] See.: for example: Yudina N. Anti-Extremism in Virtual Russia in 2014-2015. // SOVA Center. 2016. 29 June (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2012/10/d25679/).

[21] Yudina N. Anti-Extremism in Quarantine…

[22] Yudina N. In the Absence of the Familiar Article. The State Against the Incitement of Hatred and the Political Participation of Nationalists in Russia in 2019 // SOVA Center. 2020. 17 Murch (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2020/03/d42196/).

[23] For more, see: Cases of terrorist propaganda in pre-trial detention centers and places of detention // SOVA Center. 2019. 15 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2019/04/d40881/).

[24] See: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[25] Consolidated statistics on the state of criminal record in Russia for the first half of 2022 // Supreme Court website (http://cdep.ru/index.php?id=79&item=5460).

[26] Verdict handed down for participation in extremist community in Perm // SOVA Center. 2022. 15 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/12/d47369/).

[27] The sentence is also accounted for in the report on hate crimes: Yudina N. The Old and the New…

[28] The sentence is accounted for in the above mentioned report.

[29] Affiliated with Svetlana Zorya’s “Supreme Council of the RSFSR.” For more, see: Akhmetyev Mikhail. Citizens without the USSR…

[30] Anzorean Patrols: From Shariah to Extremism // Kavkazskiy uzel. 2021. 17 August (https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/365782/); Members of an extremist community convicted // Kabardino-Balkarskaya pravda. 2022. 6 April (https://kbpravda.ru/node/10829).

[31] A.U.E. movement recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2020. 17 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2020/08/d42774/)

[32] As of February 23, 2023, the list has 5339 entries.

[33] See: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[34] Yudina N. The State Has Taken up Racist Violence Again: Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2021 // SOVA Center. 2022. 10 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2022/02/d45774/).

[35] The Nevograd group is recognized as extremist // SOVA Center. 2021. 21 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/10/d45172/).

[36] Court delivers sentence in the case of Putin's mannequin tied to a pole // SOVA Center. 2020. 18 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2020/08/d42776/).

[37] On the citizens of the USSR, see: Akhmetyev Mikhail. Citizens without the USSR…

[38] “The Council” had been operating since June 2019. In March 2021 its leader Marina Melikhova was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison under Part 2 of Art. 280 of the CC (public calls for extremism on the Internet). For more about her political biography and the activities of the Krasnodar branch of “citizens of the USSR” see: A citizen of USSR from Krasnodar sentenced to imprisonment // SOVA Center. 2021. 28 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2021/03/d43925/).

[39] Other names mentioned by the court: The Union of Soviet Light Clans Power, Council of Soviet Socialist Districts [both abbreviated as USSR in Russian], Council of the Union of Soviet Socialist Districts, Supreme Council of the Union of Soviet Socialist Districts, Supreme Council of Warriors of the Union of Soviet Light Clans Power, Union of Soviet Light Clans Superpower, Supreme Council of Warriors of the Union of Soviet Light Clans Superpower, VSV Power SSSR, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

[40] For more information see: Novokuibyshevsk-based “citizens of the USSR” organization declared extremist // SOVA Center. 2022. 24 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/08/d46845/).

[41] Three Ukrainian organizations declared extremist in the Russian Federation // SOVA Center. 2022. 8 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2022/09/d46906/).

[42] For more about both decisions see: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[43] That is if you don’t count the 395 local Jehovah’s Witnesses branches banned along with their Administrative center and listed in the same paragraph with it.

[44] See: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[45] As of February 22, 2023 this list has 46 organizations.

[46] Another name is Kushkul Jamaat; according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Federal Security Service, the group had been operating in the region since 2014 and was recruiting for ISIS. The group's activities were suppressed in 2020: some members of the group were detained, while others managed to leave for Syria. At the same time, the materials collected by the special services were handed over to the Prosecutor's Office.

[47] For more see: Kravchenko M. Inappropriate Enforcement…

[48] In Irkutsk, Viktor Ochurdyapov stood in the middle of the street and shouted that he was a Buryat and a Buddhist lama. He shouted that he “has killed and will continue to kill Muslims, Islamists, and Chechens,” and urged everyone around him to follow his example. Ochurdyapov promised to “kill all the Churkas” and that “the square in the center of the city will be red with blood.” During the arrest a knife fell out of his clothes. In addition, he made xenophobic insults against Russians and “a police officer.”