This text is an excerpt from a larger report, published in Russian[1], on the enforcement of anti-extremist legislation in Russia’s online sphere. This excerpt focuses on the enforcement of criminal law.

We have discussed the characteristics of the enforcement of anti-extremist legislation, including some Internet-related cases,[2] so here we will limit our subject to the specifics of the anti-extremist criminal sanctions on the Internet. The term "extremism" hereinafter is used not in the sense it usually has in the political science realm, but rather under the unusual definition it has acquired in the context of Russia’s anti-extremist legislation.[3]

In Russia, the Internet has become available to an increasing number of people, offering unlimited possibilities to distribute every kind of content. Because cyberspace is censored very minimally, and everyone has an opportunity to speak their minds, cyber-antagonism is widespread in the Russian Internet community.

However, the number of savvy Internet users has increased among law enforcement officials as well, and since 2006, their control over the Russian segment of the Internet has become much more noticeable. Now the Russian judicial practice has accumulated substantial experience in the "war on Internet extremism.” This campaign has had an effect not only on truly dangerous instigators, such as instigators of racial hatred, but also on many others whose fault is questionable, and sometimes even non-existent.

***

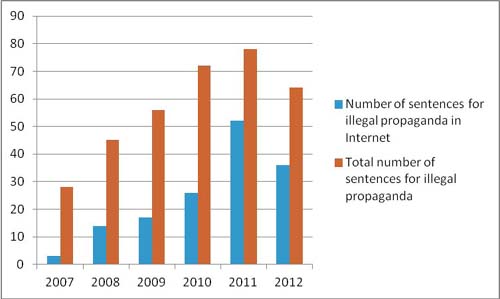

Prior to 2008, the number of convictions for propaganda specifically on the Internet was in the single digits. For example, in 2007 we only knew of three such sentences out of a total of 28 sentences, under Articles 280 and 282, for public calls to extremist activity and for incitement to racial or other similar hatred. In 2008, in just one year, the number of Internet-related convictions had already increased to 14 (out of 45). In 2009 it grew to 17 (out of 56), in 2010 there were 26 (out of 72), and in 2011 the number of such convictions increased almost twofold: there were at least 52 (out of 78 total convictions). That is to say that the majority of the "extremist propaganda" cases occur as a result of online activity. This trend continues in 2012: in the first six months there were at least 18 sentences (out of 32).

The graph below shows the dynamics of this process (the data for 2012 is a projection, assuming that the second half will be exactly the same as the first one):

This data serves as an indirect rebuttal of the statement that Russia lacks the legal framework for prosecuting "cyber-hatred,” and confirms that the existing Criminal Code articles are being successfully applied to cases of online propaganda.

The main "anti-propaganda" article of the Criminal Code in the public mind (and probably in the minds of law enforcement) is Article 282 ("incitement of national, racial, or religious enmity, abasement of human dignity”). The Criminal Code Article 280 ("Public incitement to extremist activity")[4] is used far less often.

The first of the known criminal convictions for propaganda via the Internet[5] was delivered under Article 280 of the Criminal Code, passed in 2005. However, almost simultaneously the conviction under Article 282 for publishing xenophobic materials on the Internet took place in Syktyvkar. [6] It is important to emphasize that the text of these two articles refers to public statements delivered by any means, including the Internet. However, not all online material can be considered public. For example, it can be password-protected and accessible only to a small group. In any propaganda crime, the degree of publicity constitutes a fundamental characteristic, and, while this degree of publicity is fairly obvious in cases of traditional media, it is far from obvious in cases of an Internet publication.[7] The extent of publicity has thus far not been taken into account. For example, in 2011, the court in Chuvashia issued a conviction for sending files by e-mail, which hardly qualifies as a public statement.

***

In 2007–2011 the materials that resulted in convictions for Internet propaganda were taken from the following platforms:

|

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Websites |

1 |

3[8] |

2 |

2 |

39 |

|

Social Networks |

0 |

0 |

2 (“VKontakte” in all cases) |

6 (“VKontakte” in all cases) |

25 (“VKontakte” – 20, “Odnoklassniki” – 1, unknown – 4) |

|

Blogs

|

0 |

1 (Livejournal) |

6 (Livejournal – 3, unknown-3) |

1 (unknown) |

1 (unknown) |

|

Forums |

1 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

|

Local networks |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

|

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

5 |

6 |

13 |

11 |

From the above data it is clear that by 2011, law enforcement focused its monitoring on social networks, primarily on "Vkontakte.”[9] Perhaps this is due to the fact that since 2007 this platform has been rapidly gaining popularity among many groups, including young right-wing radicals.

When analyzing the details of a particular case of "extremist content" the most important question to ask is, what is the target group? Who is the potential victim for right-wing radicals and similar groups? Unfortunately, our classification is incomplete. The convoluted, standard legal phrasing of "post on the internet files extremist" and "statements intended to stir up hatred and hostility and humiliation of groups of individuals" is extremely difficult to understand. Where possible, we have identified the following groups as the objects of animosity[10]:

|

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Immigrants from the Caucasus region |

1 |

7 |

7 |

9 |

20 |

|

Jews |

1 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

|

Komi |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Bashkirs |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Tatars |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Yezids |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Dark-skinned |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Government (incl.police officers) |

0 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Non-Slavs |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

Russians |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

|

Christians |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

"Infidels" (calls for armed jihad) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

13 |

Thus, the most frequently prosecuted online rhetoric is directed against people from the Caucasus region,[11] which is indeed quite widespread. Anti-Semitic content does not constitute the most active area of cyber-antagonism, but is still very much present. Notably, the number of convictions for anti-Semitic propaganda has remained virtually unchanged from year to year. Cases of prosecution for xenophobic propaganda against other ethnic groups are rather rare.

These materials can be classified by genre as follows[12]:

|

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Audio and video files |

1 (video clip) |

3 (video clips – 2, movie – 1) |

5 (all – video clips) |

10 (video clips – 8, movies – 2) |

24 (video clips – 20, movies – 2, songs – 2) |

|

Drawings |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Photographs |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Texts (including forum comments) |

1 (comment) |

11 (texts – 7, comments – 4) |

10 (comment – 1) |

14 (texts – 11, comments – 3) |

29 (texts –19, comment – 10) |

|

Creating a social network users group |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

It is worth noting, that, while before 2009 sentences were given predominantly for text materials, in 2010-2011 the number of convictions for multimedia content is almost equal to the number for texts. This is not surprising: a movie or video recording has much greater visual impact than any text, linking to them has become easier, and sheer number of online videos has increased as well.

Remarkably, in most cases the video in question is not produced or uploaded to the Internet by the offender; he simply published a link to a video posted elsewhere (for example, on Youtube). Of course, it is possible that the user, who posts a link to a video on a social network, is the one who put the video itself online as well. However, in most cases, we believe that these are different people. We also believe that it would make more sense to identify the person who originally posted the video and, most importantly, the one who created it (especially since the video often depicts an actual violent crime), instead of prosecuting those who share the links. This holds true even if we assume that in each case they had shared proven inflammatory intent.

***

As for the sentences given for the textual materials, most of these materials are no longer available, preventing us from assessing the degree of public endangerment. We only are able to note that by 2011, the number of sentences for individual comments on social networks, blogs and forums has increased. Most likely, these people were selected at random, were not excessively popular among the far-right, and did not have any significant audience. Thus, the prosecution increasingly went after the people whose statements, while clearly racist and unacceptable from an ethical point of view, did not represent any significant danger to society.

In the early stages of fighting online "extremism" the law enforcement focused on the level of “significance” of Internet propagandists and the extent to which their acts represented danger. In 2007, a court in the Kaluga region convicted a Nazi skinhead group for online distribution of a video showing themselves beating up people of "non-Slavic appearance." In 2008, the creator of a neo-Nazi website that hosted bomb recipes and called for violence was convicted in Lipetsk. In Vladivostok, the leader of a local neo-Nazi group, Soiuz Slavian (Union of Slavs), was convicted in 2009. Despite these cases, the convictions of leaders and right-wing ideologues were rare, and those persecuted were essentially the rank-and-file content distributors. By 2010-2011, the practice of criminal prosecution for xenophobia was deliberately aimed toward persecuting authors of re-posts, links, online comments, and for isolated statements in social networks even in cases where the real audience for those texts was obviously very small.

Against the background of the unimpeded functioning of ultra-right social network groups that coordinate violent actions and publish "hit lists" with personal data and photos of "enemies," such opposition looks like a simulated fight against cyber-hate. This serves only one purpose well – the statistics look good on the report. The number of convictions is inflated by prosecuting statements which are either not inherently dangerous or not available widely enough to warrant prosecution[13] (regretfully, the persecution of hate propaganda outside the Internet follows the same pattern).

Some Internet-related convictions are simply inappropriate. SOVA center knows of at least six such sentences. The most resonant is the sentence of blogger Savva Terentyev, delivered on July 7, 2008, by the Syktyvkar City Court. Terentyev was found guilty of inciting social hatred against police officers (the Criminal Code article 282) and sentenced to one year imprisonment with a probation period of one year for an anti-police comment in an online diary.[14] In 2009, the journalist Irek Murtazin[15] and the chairman of the Tatar Public Center Rafis Kashapov[16] were convicted in Kazan. In 2010 Islamly Ilham Sarjuddin-ogly was convicted for online distribution of works by the Turkish theologian Said Nursi.[17] There were two more convictions in 2011 – one for the blogger Irina Dedyukhina[18] in Izhevsk and one for Dmitry Lebedev[19] from the city of Gatchina, Leningrad region.

However, the penalties for online distribution are not usually severe. The court decisions on these prisoners show the following distribution:

|

|

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Total number of offenders convicted.

Of those: |

10 |

14 |

17 |

30 |

52 |

|

Suspended sentence |

1 |

5 |

6 |

15 |

24 |

|

Fines |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

11 |

|

Mandatory Labor |

0 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

9 |

|

Correctional Labor |

0 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

Restriction of Freedom |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Incarceration |

8 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

|

Compulsory Treatment |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Almost all convictions that involved prison terms were delivered in conjunction with punishment for additional (mostly violent) crimes. In some cases, however, we consider them unduly harsh, as with the sentence passed in 2011, in the Komi Republic, for anti-Komi comments published on one forum. In yet another case, there were justifiable doubts as to the authors’ mental health, and this, we believe, nullifies any possible danger to the public from their texts. The materials in question were blogs of the group, Genghis Chelyabinsk; in June, 2010, two of Genghis Chelyabinsk’s four members were each sentenced to 2 years and 6 months of imprisonment.

The share of offenders who receive suspended sentences without any additional penalties is on the rise (the only exception to this is the 2008 "prohibition on trade" delivered to a police officer from the Leningrad region for maintaining a neo-Nazi blog and website). Such a penalty, in fact, constitutes a non-punishment, and its effectiveness against ideologically motivated offenders is in serious doubt. We consider other types of non-custodial penalties to be much more appropriate, such as compulsory labor or fines. Unfortunately, the share of such penalties has been dropping in comparison to the share of suspended sentences.

***

Criminal prosecution for hateful cyber-propaganda has a wide geographical span (at least 50 regions of the country). Chelyabinsk region is in statistical lead (6 sentences). It is followed by Arkhangelsk Region and the Republic of Chuvashia, the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous District (5 sentences); Kaluga, Kursk and Novgorod Regions and the Republic of Karelia (4 sentences); the Regions of Vladimir, Pskov, Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, Krasnodar Kray, the Republic of Adygea (3 sentences each); the regions of Voronezh, Kurgan, Lipetsk, Novosibirsk, Samara, Krasnodar, the Republic of Bashkortostan (2 sentences); the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, the Regions of Amur, Arkhangelsk, Astrakhan, Bryansk, Volgograd, Ivanovo, Kemerovo and Kostroma, Kamchatka Kray, and the regions of Leningrad, Moscow, Murmansk, Novgorod, Penza, Sakhalin, Smolensk and Tula, Krasnoyarsk Kray, the Republics of Altai, Buryatia, Mari El, and Udmurtia (one each).

It is noteworthy

that online hate propaganda is not very actively prosecuted in the

***

Overall, the practices of the Russian law enforcement in combating cyber-hate can be called anything but successful. Quantitative indicators of anti-extremist measures undertaken by police officers are growing, but the quality of law enforcement deteriorates.

Materials that directly incite violence or are related to the actual use of violence, such as the "hit list" or "manuals on street terror,” which provides details of how to dispatch “an enemy," are still openly posted but remain virtually unnoticed by Russian law enforcement agencies. The recorded number of prosecutions for these actually dangerous incitements is exceedingly small.

Law enforcement officers for the most part go after random, individual people for isolated statements. The number of these statements on the Internet is huge and dealing with them in such a manner is simply not rational. We are also seeing an ever greater number of inappropriate and unjustified court decisions.

Such law enforcement is not merely selective, but becomes simply chaotic. As a result neither the public, law enforcement officers, nor various radical groups themselves have any consensus on what, in fact, should be prohibited.

The Russian

security services already have the experience of good-quality work. The

November, 2009 apprehension by law enforcement officials of Nikita Tikhonov and

Yevgenia Khasis, later convicted for the murder of lawyer Stanislav Markelov

and journalist Anastasia Baburova, constitutes an example of a proper use of

the Internet. Specialists from the Department of Technical Activities of the

Unfortunately, we have very few examples of this sort. Russian ultra-nationalists feel confident to operate online with impunity and continue coordinating their illegal activities via the Internet. The majority of Russian law enforcement officers have taken the path of least resistance, achieving better statistics for countering extremism by prosecuting minor online publications and individual comments.

The efforts of the fighters against extremism on the Internet should be focused on disarming dangerous groups and individuals who practice or directly incite violence. Fighting against comments on social networks or the distribution of stand-alone materials is best left to community organizations and activists. They not only can engage in an active debate, but also may be able to persuade hosting providers or the owners of social networking sites to remove socially dangerous content.

[1] Yudina, Natalia. “Vurtual Anti-Extremism: Peculiarities of enforcing the anti-extremist law on the Internet in Russia (2007–2011)”//SOVA Center. 2012. 17 September (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2012/09/d25322/).

[2] This topic is covered in many news articles on our website; our periodic reports also contain a lot of related information. The links to our most detailed annual reports can be found in the “Racism and Xenophobia” and “Misuse of anti-extremism” segments on our website (the English versions can be found at http://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/ and http://www.sova-center.ru/en/misuse/reports-analyses/). These reports were also included in Xenophobia, Freedom of Conscience and Anti-Extremism in Russia in 2011. Moscow: SOVA Center, 2012.

[3] This definition is available in English from the following source: Opinion on the Federal Law on Combating Extremist Activity of the Russian Federation // European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission). 2012. 20 June (http://www.venice.coe.int/docs/2012/CDL-AD%282012%29016-e.pdf). P.7

[4] For additional details on the application of Article 280 see: Yudina, N. “Shooting sparrows with a cannon: the review of law enforcement practices relating to the Criminal Code Article 280 in 2005–2010” // SOVA Center. 2010. 25 October (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2010/10/d20081/).

[5] In March 2005 in Kemerovo Denis Chuprunov, a law school student, who published articles in the online newspaper Russkoe Znamia (the Russian Banner) which resided on the site of the organization Soiuz Russkogo Naroda (the Union of the Russian People) since 1998, was found guilty under Article 280 part 2.

[6] Kozhevnikova, Galina. Protivodeistvie radikal’nomu natsionalizmu: praktika gosudarstva i obschestvennykh organizatsii (Opposing Radical Nationalism: the efforts by civic organizations and the state // SOVA Center. 2005. 29 April (http://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2005/04/d4436/).

[7] See: Yudina Natalia, Alperovich Vera, Verkhovsky Alexander. Between Manezhnaya and Bolotnaya: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2011 // SOVA Center. 2012. April 5. Chapter “Criminal Prosecution of Propaganda” (http://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2012/04/d24088/#_Toc320809208).

[8] All three 2008 episodes have to do with creating personal websites, there is no information for the other years.

[9] VKontakte (vk.com) is the Russian counterpart to Facebook, the most popular social network platform in Russia at this time. It also has to be taken into account that, ever since Livejournal.com was created, it has become Russia’s most popular blogging platform and until recently was the principal area of unrestricted political discussion in the country.

[10] The data is based primarily on reports from the Prosecutor’s Offices. The offending materials, could contain rhetoric against several groups at once.

[11] Notably, the most frequent target of attacks by members of the radical ultra-right from 2007–2011 were not migrants from the Caucasus region, but those from Central Asia. See the attack statistics in SOVA Center reports, for example in the appendix to: Alperovich V., Yudina N. Spring 2012: Ultra-right on the Streets, Law Enforcement on the Web // SOVA Center. 2012. July 27 (http://www.sova-center.ru/files/xeno/tables22_06_2012.doc).

[12] One conviction could include materials from several different genres.

[13] For example, in November, 2011, the Syktyvkar City Court (Komi Republic) delivered a one-year suspended sentence to 33-year local resident, Georgii Borman, who between May to July 2010 published several xenophobic comments to articles on the Republic of Komi Business News website under different aliases. The comments remained visible to the public only for a few hours, after which they were promptly removed by moderators.

As another example, in October, 2011, the Kalinin District Court in Cheboksary (Chuvashia) sentenced a 25-year-old local woman under Part 1 of Art. 282 for making Mein Kampf publicly available via the local file-sharing network of a local provider.

[14] In our opinion, the legal qualification of the blogger’s act contained obvious errors – the blog, containing an offending comment, was viewed as having the same status as mass media; the police officers were recognized as a social group in need of protection offered by the anti-extremist legislation. Most importantly, the basic principle of criminal law was violated: not any act, fitting under the Criminal Code formulas, is a crime, but only the act constituting social danger. No additional social danger was observed in the case, and the spectacle of prosecutors, judges and experts drawn into this essentially absurd case has discredited all the stakeholders and the legislation itself. For more details see: “The verdict was delivered in the case of Savva Terentyev” // SOVA Center. 2008. 7 July (http://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2008/07/d13743/).

[15] On November 26, 2009 the Kirov District Court of Kazan convicted I. Murtazin under the Criminal Code article. 129 part 2 ("slander"), Article 282 Part 1 ("inciting hatred of a social group"); the charge under Part 2 , paragraph "a" of Article 282 (the same, “with the threat of violence") was dropped. Former Press Secretary to President Shaimiev was sentenced to 1 year and 9 months in a penal colony. For more details see: “The Verdict Delivered to Irek Murtazin” // SOVA Center. 2009. 26 November (http://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2009/11/d17410/).

[16] R. Kashapov was found guilty under Article. 282 Part 1 ("inciting hatred or enmity") and sentenced to fifteen years' imprisonment for an article in his blog. In our view, the text contains no indication of hatred on either national or religious grounds. Their main aim is at the Russian state of different eras, which, in the author’s opinion, pursued a policy of forced Russification and Christianization. For more details see: Rafis Kashapov Received the Verdict // SOVA Center. 2009. 24 April (http://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2009/04/d15848/).

[17] On August 18, 2010 the Nizhny Novgorod District Court of Nizhniy Novgorod found the Azerbaijani citizen Islamly Ilham Sarjuddin-ogly guilty under Part 1 of Article 282 and delivered a suspended sentence of 8 months.

[18] August 9, 2011 the October District Court of Izhevsk found I. Dedyuhova guilty and fined her 20 thousand rubles for publishing on her blog under the alias “ogurcova” in 2010. In our opinion, the text can indeed by viewed as inciting hostility towards Chechens, because the author uses the word "Chechen" only in a negative context, and calls not to allocate funds for sending Chechen children to sports camps. However, we believe that a single such text should not constitute a sufficient cause for prosecution. It would have been much more appropriate to command the author to remove the text from her page and prohibit its further copying.

[19] On May 20, 2011 the Gatchina City Court of Leningrad Region found Dmitry Lebedev guilty under Article. 282 Part 1 and sentenced him to one year imprisonment for his posts on VKontakte, directed against the head of the Russian Orthodox Church and members of the clergy. Lebedev was a member of a group called "Kill the Patriarch." However, Lebedev never actually called for illegal actions against the Orthodox community – the Patriarch was supposed to be killed by a mystical force. Thus, the sentence was inappropriate.

[20] Gladkii Maxim, Burtin Shura, Nazdracheva Lyudmila, Rudnitskaia Anna. Caught on VKontakte // Russkii Reporter. 2009. No. 43.