Summary

The results of the past year have been alarming. Although the overall level of xenophobic violence did not increase as dramatically as in the preceding year, the situation has deteriorated qualitatively: attacks have become more brutal, the number of killings has increased, and some victims, including murder victims, were children.

The number of acts of vandalism motivated by hatred doubled in 2025. The share of more dangerous acts (including arson and explosions) also increased.

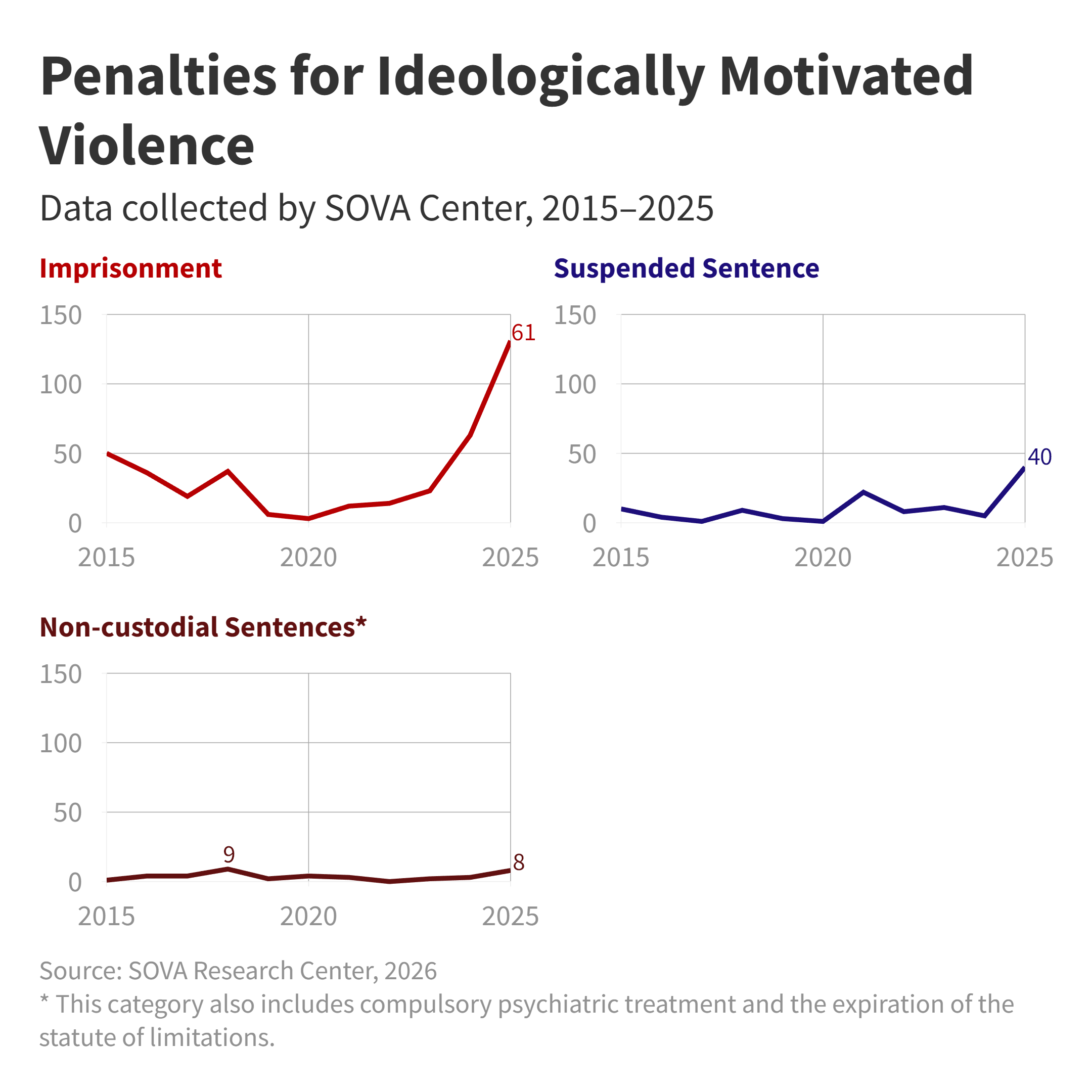

Law enforcement agencies intensified their efforts to counter ideologically motivated violence. In particular, participants in several radical far-right groups were convicted last year, including members of the revived NS/WP organization. We also received reports regarding arrests of new small groups of young neo-Nazis. Overall, excluding the numerous convictions related to the riots at Makhachkala airport, the number of people convicted for ideologically motivated violence more than doubled in 2025 compared to 2024. Apparently, this intensification of law enforcement activity was instrumental in slowing down the quantitative growth of violence.

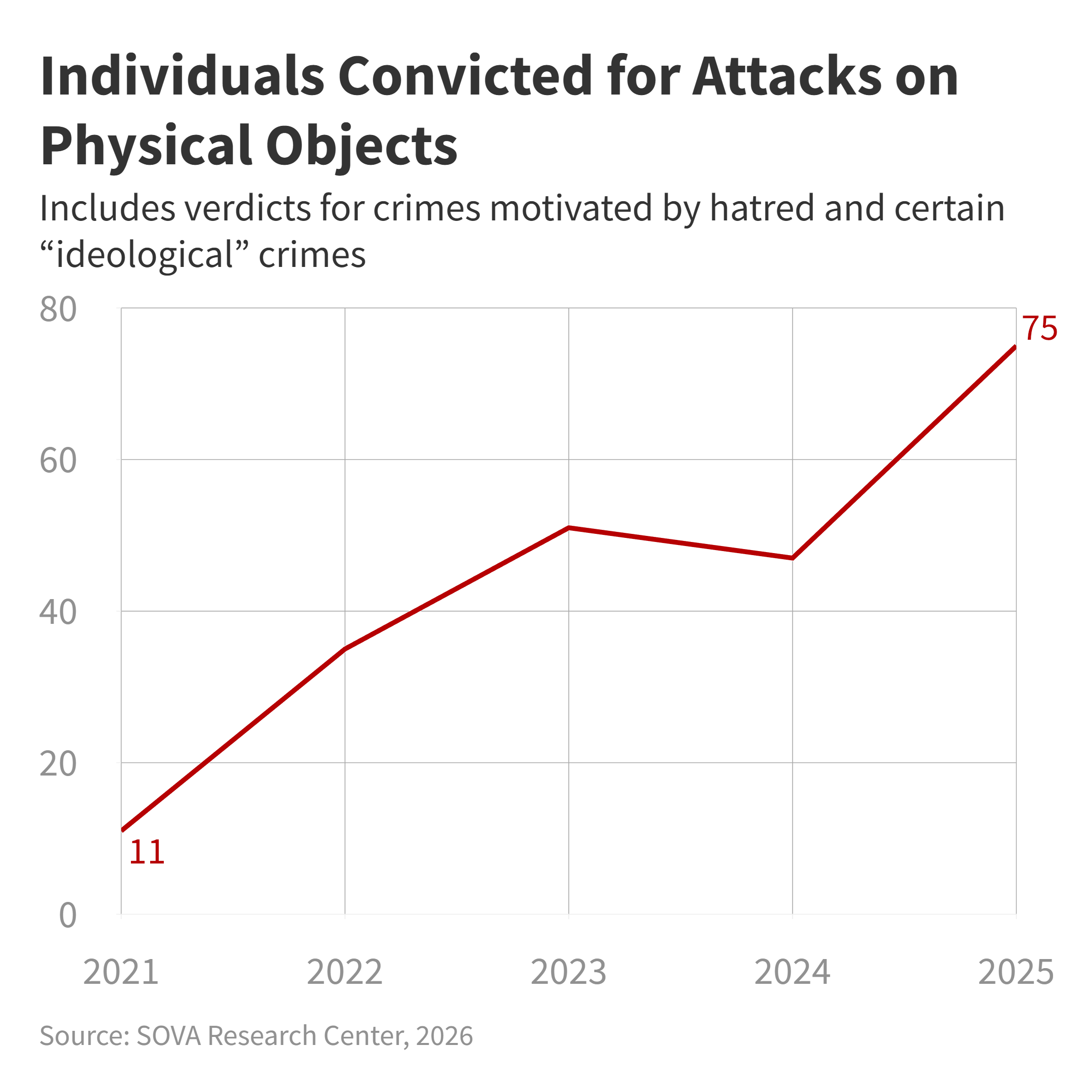

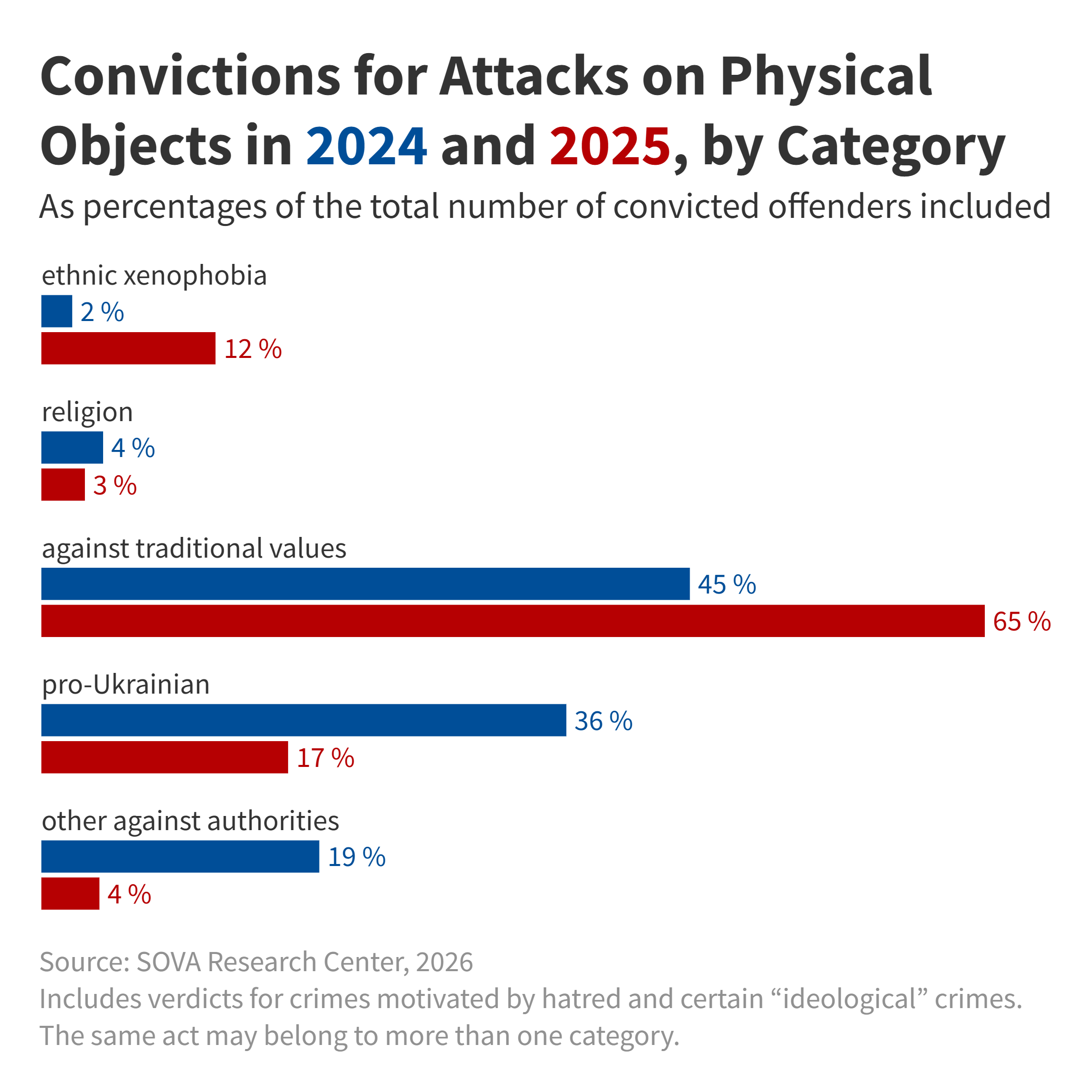

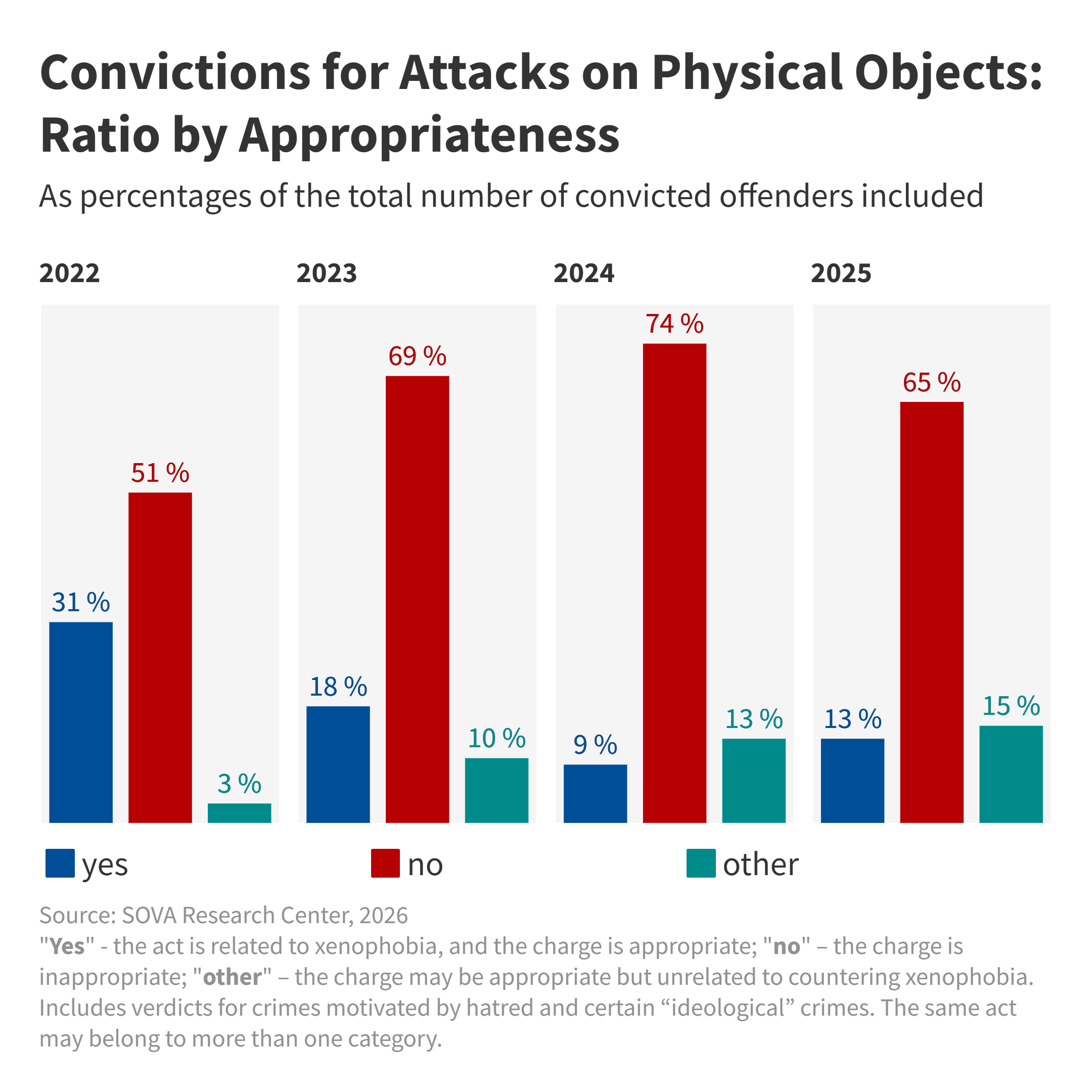

Law enforcement has also stepped up its efforts to counter attacks on material objects; 60% more people faced sanctions than the year before. However, for the past four years, this enforcement has targeted primarily not hate crimes, but other actions against material objects. On the one hand, in 2025, more sentences were issued for vandalism motivated by ethnic xenophobia and fewer – for protest actions against the authorities (including in connection with Ukraine). On the other hand, the number of sentences in defense of “traditional values”[1] increased more than twofold and accounted for 65% of the total. The share of verdicts we considered clearly inappropriate also amounted to 65 % – though this is less than last year (74%) or two years ago (69%).

Thus, 2025 was marked by an increase in the social danger posed by hate crimes. Heightened efforts to counter xenophobic violence inspire some cautious optimism, but we cannot say the same of law enforcement practices regarding attacks on material objects. These appear to serve primarily ideological rather than law enforcement purposes.

Table of Contents

Summary

Systematic

Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

Attacks against “Ethnic

Outsiders”

Attacks against LGBT+ and

“in Defense of Morality”

Attacks against

Ideological Opponents

Religious Xenophobia

Other Attacks

Crimes against Property

Criminal Prosecution for

Violence

Criminal Prosecution for

Crimes against Property

This report by SOVA Center examines offenses commonly referred to as hate crimes – that is, ordinary criminal offenses committed out of ethnic, religious, or similar hostility or prejudice[2] – and the state’s response to such crimes.

Russian legislation also classifies as hate crimes offenses committed out of political and ideological hostility. The inclusion of these types of hostility in the definition of hate crime is relatively rare in democratic countries and remains debatable.

In this report, we do not examine such crimes unless committed by groups ideologically oriented towards committing xenophobic hate crimes in general. At the same time, we do analyze law enforcement practices regarding certain ideologically constructed provisions of the Criminal Code (CC) related to attacks on material objects.

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

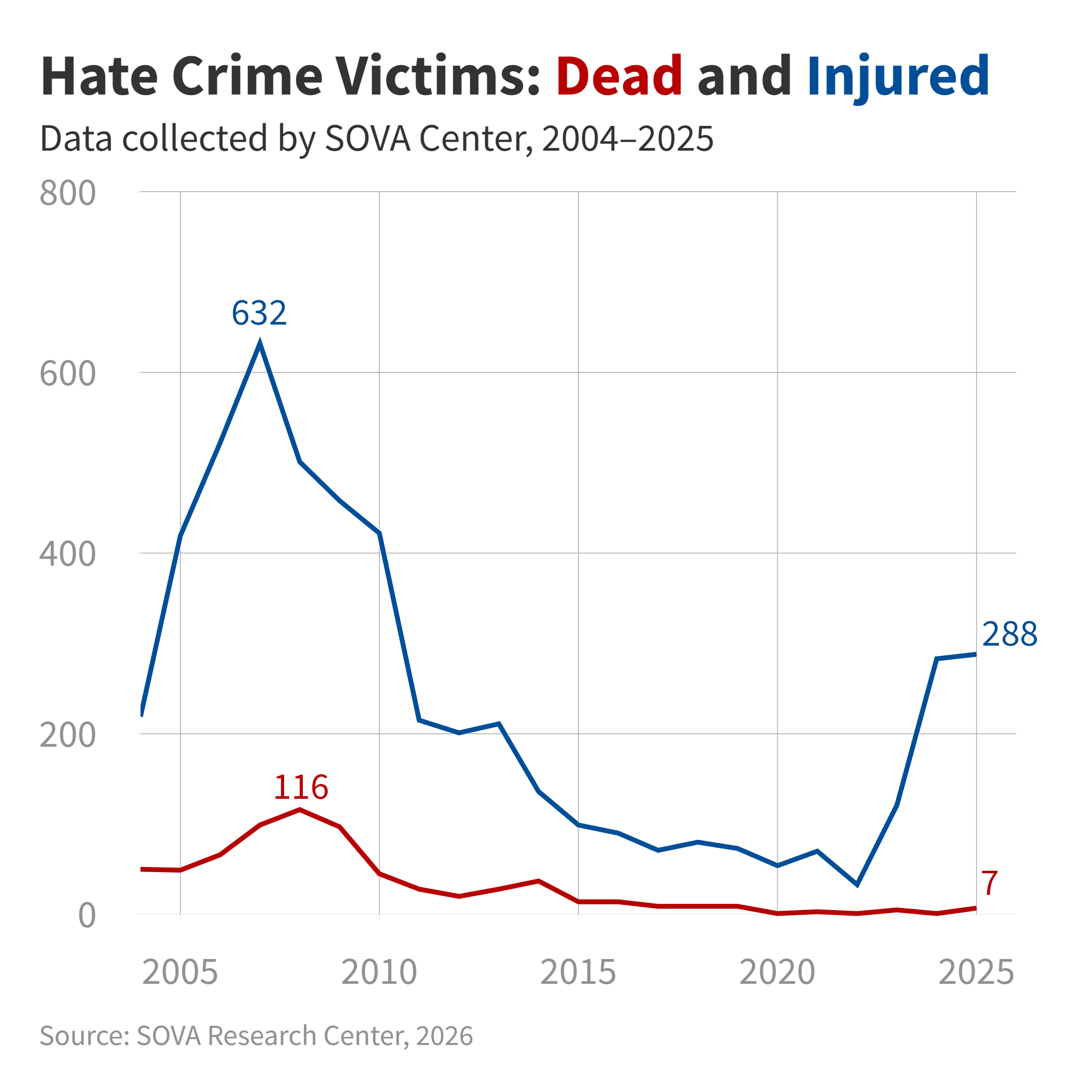

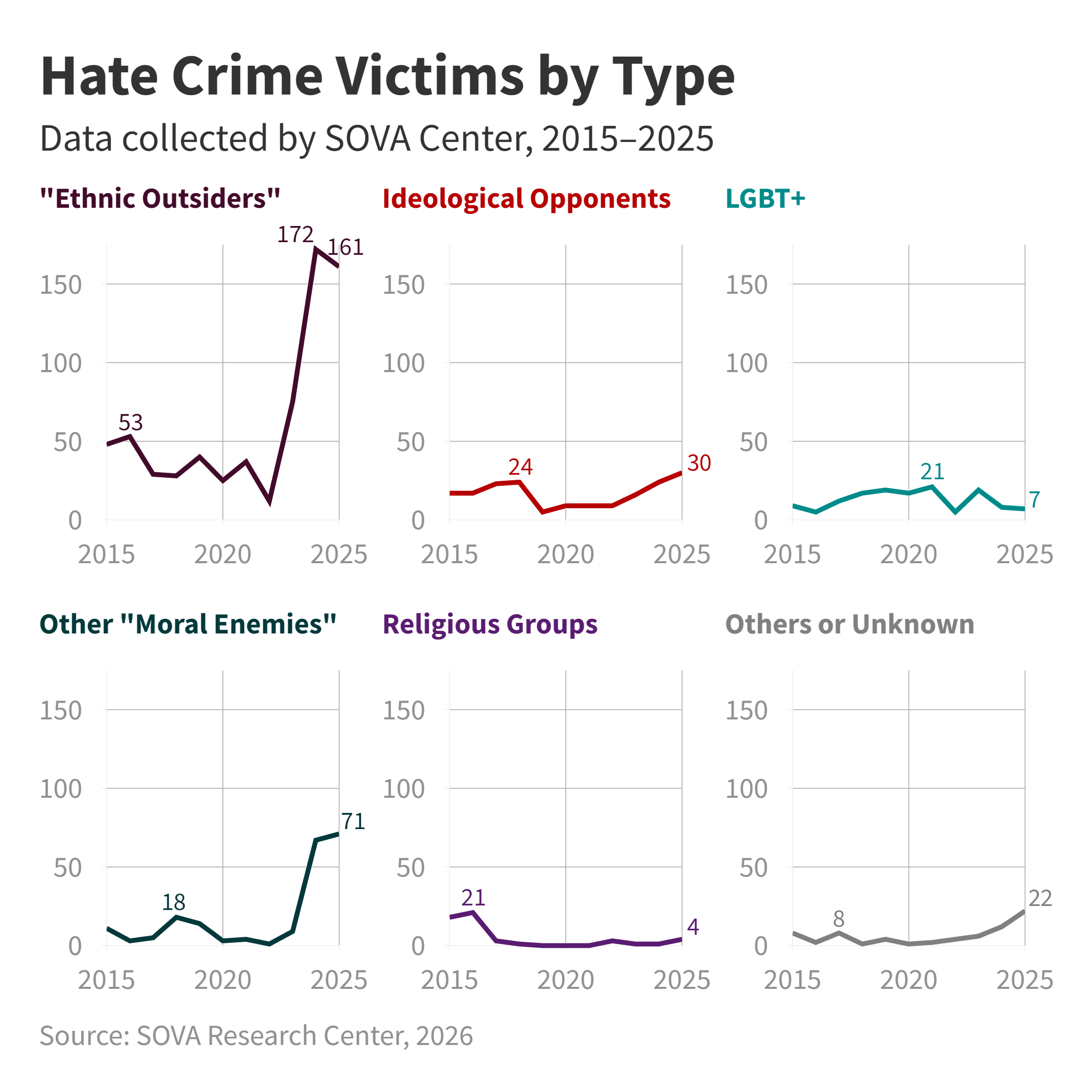

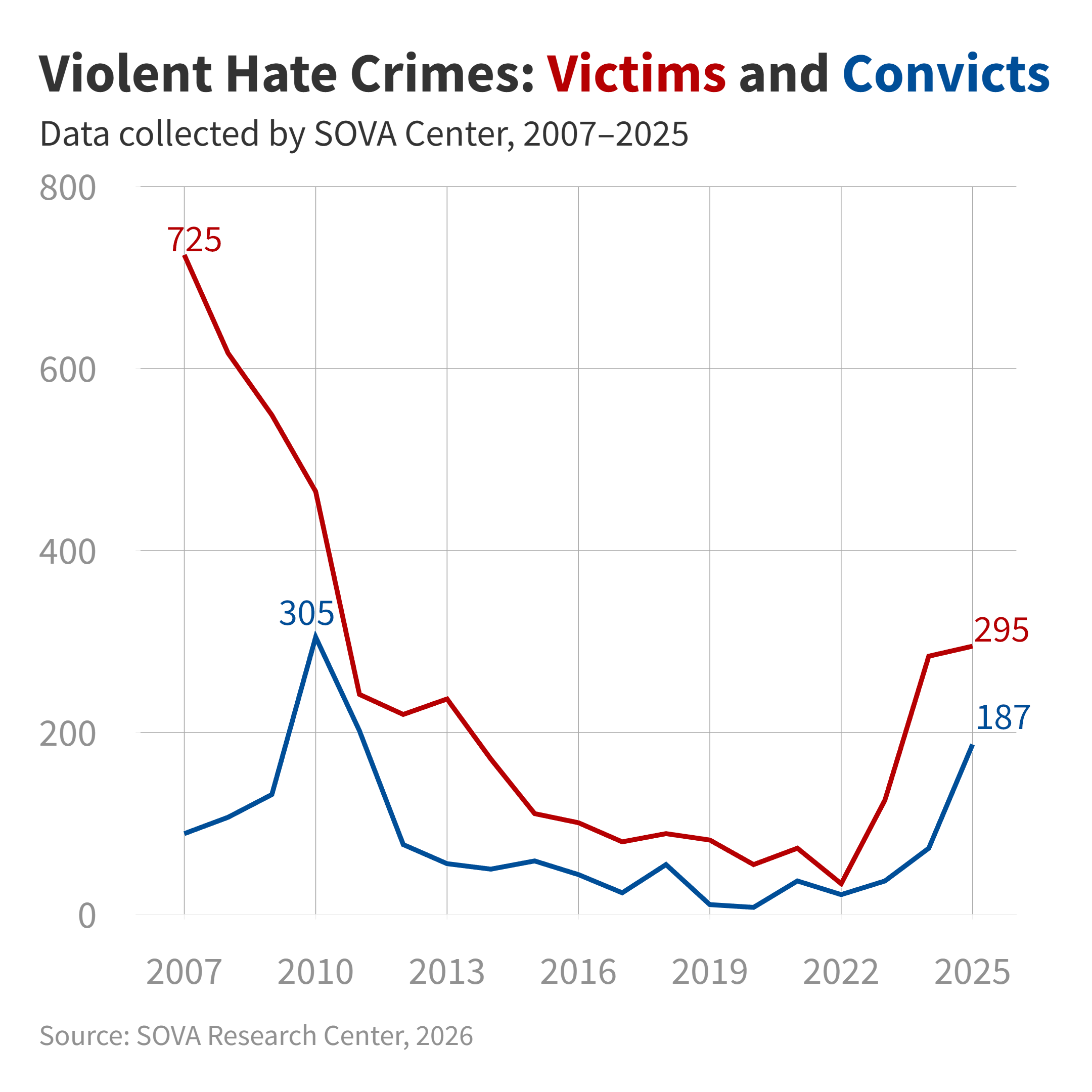

According to SOVA Center monitoring, 295 individuals were victims of ideologically motivated violence in 2025, seven of whom died. In 2024, we recorded 284 victims, including one fatality.[3] It should be noted that last year’s data are not yet final, as information about some attacks reaches us with delays.[4] Thus, we record a slight increase in the number of attacks, although we can assume that the growth was far less dramatic than the year before. At the same time, judging by the number of killings, the brutality of attacks has increased.

Unfortunately, we cannot verify our data against official statistics; the data is not publicly available. We understand that our figures are inevitably incomplete. For instance, we do not include data from the North Caucasus republics, where our methodology simply does not work.[5] We also know very little about the activities of militant groups operating in the name of ethnic minorities. Thus, our data in no way reflects the real level of racist violence nationwide. Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings, we assess dynamics and major trends to some extent, since our methodology has changed little since 2004.[6]

Each year, we write about the problems we face in gathering information, and nothing changed in this regard over the past year. Extracting data from media reports, which often describe hate crimes in ways that make them hard to identify, remains difficult, and we learn virtually nothing from police reports. Victims themselves are also reluctant to contact law enforcement (due to traditional distrust of the police) or human rights organizations.

For the third year in a row, we have learned about the majority of attacks from far-right Telegram channels, where a new generation of neo-Nazis publishes daily “direct action” reports. Unlike a decade ago, today’s far-right youth are far more committed to secrecy: attackers’ faces are unidentifiable in videos, and the time and place of attacks are often unclear.

We treat such information with caution. For example, we did not include in our statistics episodes where far-right teenagers desecrate corpses (three such cases were known last year), since their authenticity is questionable, and we found no independent confirmation of the alleged killings. Overall, however, we tend to regard video reports from small far-right groups as reliable, since in a number of cases, they have been corroborated by law enforcement, which managed to detain some of the attackers.

Some of these videos were timed to dates significant for the far right: Hitler’s birthday (April 20); the “hatred and revenge day” (May 5, the 40th day after the death of prominent neo-Nazi Maxim “Adolf” Bazylev); the memorial day of another “white hero,” Dmitry Borovikov, leader of the St. Petersburg neo-Nazi group Combat Terrorist Organization (May 19); and the death anniversary of Maxim “Tesak” Martsinkevich (September 16). Alongside these older dates, attacks last year also commemorated new “heroes,”[7] such as the administrator of the popular far-right Telegram channel Razgrom or Andrei “Bloodman” Pronsky, a leader of the revived NS/WP.[8]

Of course, the rally that was once the main annual far-right event – the Russian March on November 4 – also received its share of attention. Although the march itself was very modest, several attack videos were deliberately timed to coincide with that date.

From the footage, it is still hard to identify the region where the attacks took place. Based on fragmentary data, we recorded attacks in 22 regions in 2025, though the actual number is likely higher (there were at least 23 in 2024).[9] Unexpectedly, in contrast to previous years, the Moscow Region ranked first in levels of violence, followed by Moscow and St. Petersburg. A notable number of victims were recorded in the Novosibirsk Region, the Chelyabinsk Region, and in Primorsky Krai. Attacks for the second year in a row were also reported in the Vladimir, Sverdlovsk, and Tyumen Regions, as well as in Stavropol Krai.

Attacks against “Ethnic Outsiders”

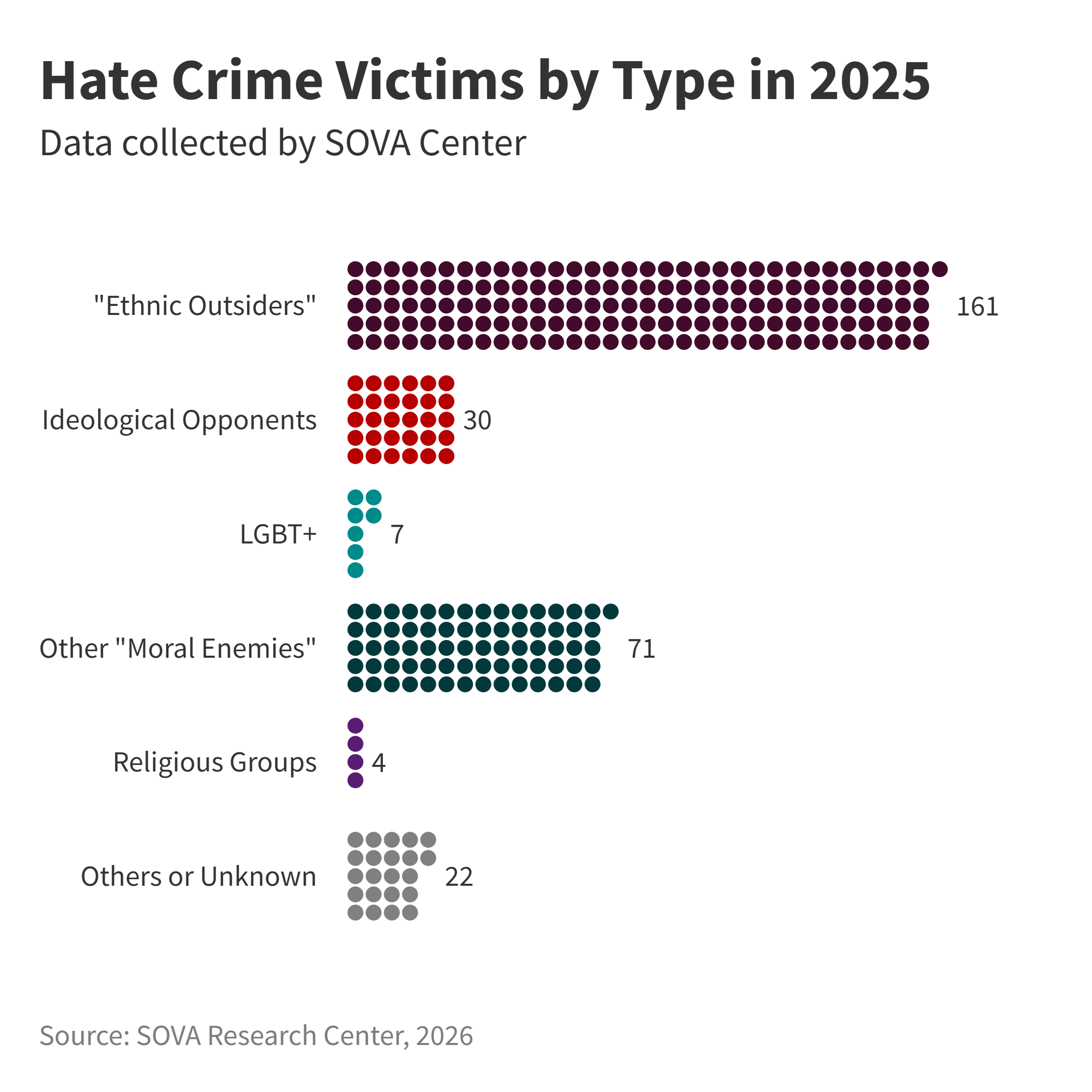

In 2025, we recorded 161 attacks on ethnic grounds – that is, attacks against people visually perceived by attackers as ethnic outsiders. This is slightly fewer than the previous year (172 attacks).

Victims in this category included natives of Central Asia and the Caucasus, people of color, and individuals we identified only as having “non-Slavic appearance.” Attacks against the latter group have been particularly brutal. Four people were killed, including two children.

Both children were victims of teenage neo-Nazis. A major media outcry followed an armed attack by a 15-year-old student, Timofei K., against a school in the Gorki-2 village near Odintsovo (the Moscow Region) in December, which resulted in the stabbing death of 10-year-old Kobiljon Aliev[10] from Tajikistan. Another child, a 9-year-old from Kyrgyzstan, was killed by a 14-year-old teenager in Trudovaya neighborhood of the Dmitrov Municipal Area in the Moscow Region.[11]

A high-profile incident should be mentioned separately: the death of 37-year-old Armenian-born Gor (Grisha) Ovakimyan during a raid by the “Russian Community” (Russkaya Obschina) on an apartment in Vsevolozhsk of the Leningrad Region. We do not include him in our victim count, since we cannot confirm the attack; the prevailing version states that Ovakimyan died in a fire that erupted during the conflict. A 24-year-old woman was also injured and hospitalized.[12]

Last year, we encountered at least five cases of so-called “white wagons.”[13] For example, a raid dedicated to Hitler’s birthday took place on a commuter train in Sergiev Posad on April 21.

We learned of seven attacks on people of color last year (vs. three in 2024). For instance, a Nigerian citizen was assaulted in St. Petersburg. In Moscow, Francine Villa, a Black resident of Russia, complained of being beaten and insulted by neighbors on ethnic grounds.

Anti-Roma rhetoric and attacks on Roma have continued in Russia. In May, in the village of Gornozavodskoye in Stavropol Krai, a teenager attacked a Roma child. In front of others, he grabbed the child by the hair, demanded an apology for being Roma, and forced the child to kiss his feet.

In 2025, in addition to individual attacks, we recorded a large-scale public anti-Roma incident. In the village of Podlesnoye of the Saratov Region, the death of a teenager in a traffic accident caused by a local Roma resident triggered a spontaneous rally with accusations against the Roma community. These included everyday grievances (violations of living standards and traffic rules) as well as Roma’s alleged criminality and evading mobilization for the “special military operation.” No violence took place, but the situation was apparently so tense that the Roma community hastily left the village immediately afterwards.

There were also attacks motivated by ethnic hatred against ethnic Russians. We learned of two such cases last year (vs. three in 2024). The victims were residents of the Magadan Region who were beaten by three foreigners during a traffic conflict, accompanied by xenophobic slurs.

For the second year in a row, we observed no physical attacks on Jews. However, even in the preceding years, such attacks rarely exceeded one per year.

Traditionally, alongside “ethnic outsiders,” victims also include people beaten “by association.” For example, two people were attacked in the Chelyabinsk Region, namely Ural Federal University lecturer Rustam Ganiev (for being, as the attacker put it, “nerus’”, i.e. “not Russian”) and his wife Lyudmila (“for being his wife”). In Sergiev Posad, passengers on a commuter train were assaulted for trying to defend people beaten by far-right activists during the aforementioned “white wagon” raid.

Attacks against LGBT+ and “in Defense of Morality”

The number of attacks on LGBT+ people remained roughly at the same level as the year before. SOVA Center recorded seven victims (eight in 2024).[14]

LGBT+ people fall into a group we categorized as “moral enemies” of the neo-Nazis, and attacks on them are a common form of far-right violence. The category of those said to undermine the nation’s moral fabric – whom far-right activists call “bio-trash” – also includes homeless people,[15] those mistaken for being drunk, drug users, and drug dealers.[16] Far-right activists also place alleged pedophiles in this same category, continuing the traditions of Maxim Martsinkevich’s Occupy Pedophiliay project. The latter are not only subjected to physical violence but also often deliberately humiliated for video recordings.

To the attackers, such victims can be ethnically “one of their own.” However, in some cases, the victim is also “non-Russian” (for example, a Central Asian native lured to a fake date with a minor), which raises the intensity of hatred. In such cases, the motive is mixed.

Collecting information about these victims is difficult because they are unwilling to talk about what happened or because of their social marginalization. Nevertheless, we learned of 79 such attacks in 2025[17] (vs. 75 in 2024). For the second year in a row, this is the second-largest victim group in our grim statistics.

Attacks against Ideological Opponents

The number of attacks by far-right activists against their political, ideological, or “stylistic” opponents also increased compared to 2024. We counted 30 people beaten (vs. 25 in 2024).[18]

The majority of victims in this group were anti-fascists or people mistaken for them (20 individuals). Among political opponents, those harmed included visitors to the Open Space co-working center in Moscow who had gathered for the traditional January 19 event to commemorate victims of neo-Nazis.[19]

In Moscow, RusNews journalist Konstantin Zharov and a 17-year-old teenager returning from an evening of writing letters to political prisoners were beaten because of their long hair and Yabloko party pins.

In St. Petersburg, an elderly man who resembled Vladimir Lenin was beaten by far-right activists “to avenge the revolution.”

The remaining victims were non-political subculture youth (three punks and other young people of a generally “nonconformist” appearance).

Religious Xenophobia

In Russia, violence driven by religious xenophobia occurs far less frequently than violence driven by ethnic xenophobia. Nonetheless, four such attacks were recorded last year (vs. one in 2024).

In Klimovsk of the Moscow Region, two employees of a church shop at the Church of St. Sergius of Podolsk were attacked. Two Muslim women also suffered in xenophobic attacks: one was beaten in the town of Rodniki in the Ivanovo Region, and the other was stabbed in the back in Saratov.

In addition to direct attacks, there were also cases of serious online threats. For example, blogger Vladislav Pozdnyakov, founder of the Male State community (designated extremist in Russia), issued threats on his Telegram channel against Mata Tepsaeva, a trichologist in a private clinic in Moscow, who allegedly refused to treat a male patient for religious reasons.[20] The threats and ensuing public outcry prompted the doctor to resign from the clinic.

Other Attacks

A particularly brutal attack on children in Domodedovo (the Moscow Region) stands out. A teenager armed with a hammer and a knife attacked two girls from behind as they were walking, sprayed them with pepper spray, struck one of them several times with the hammer, and slashed the other with the knife. One victim managed to escape; the other died in hospital from her injuries. The attacker was detained. In one of his notes, he described himself as an “incel” and cited this as the reason for the attack.

In some cases, we cannot precisely determine a target and can only say that the attack was motivated by ethnic hatred or other unspecified hatred. As a rule, we learn about such incidents from official announcements that an investigation has been completed and the case sent to court. In such instances, the hate motive is indicated by the relevant clause in the CC article. Sometimes people are beaten “by association” (see above).

The total number of “other” victims, i.e. those we did not specifically classify, reached 22 in 2025 (vs. 12 the year before).

Crimes against Property

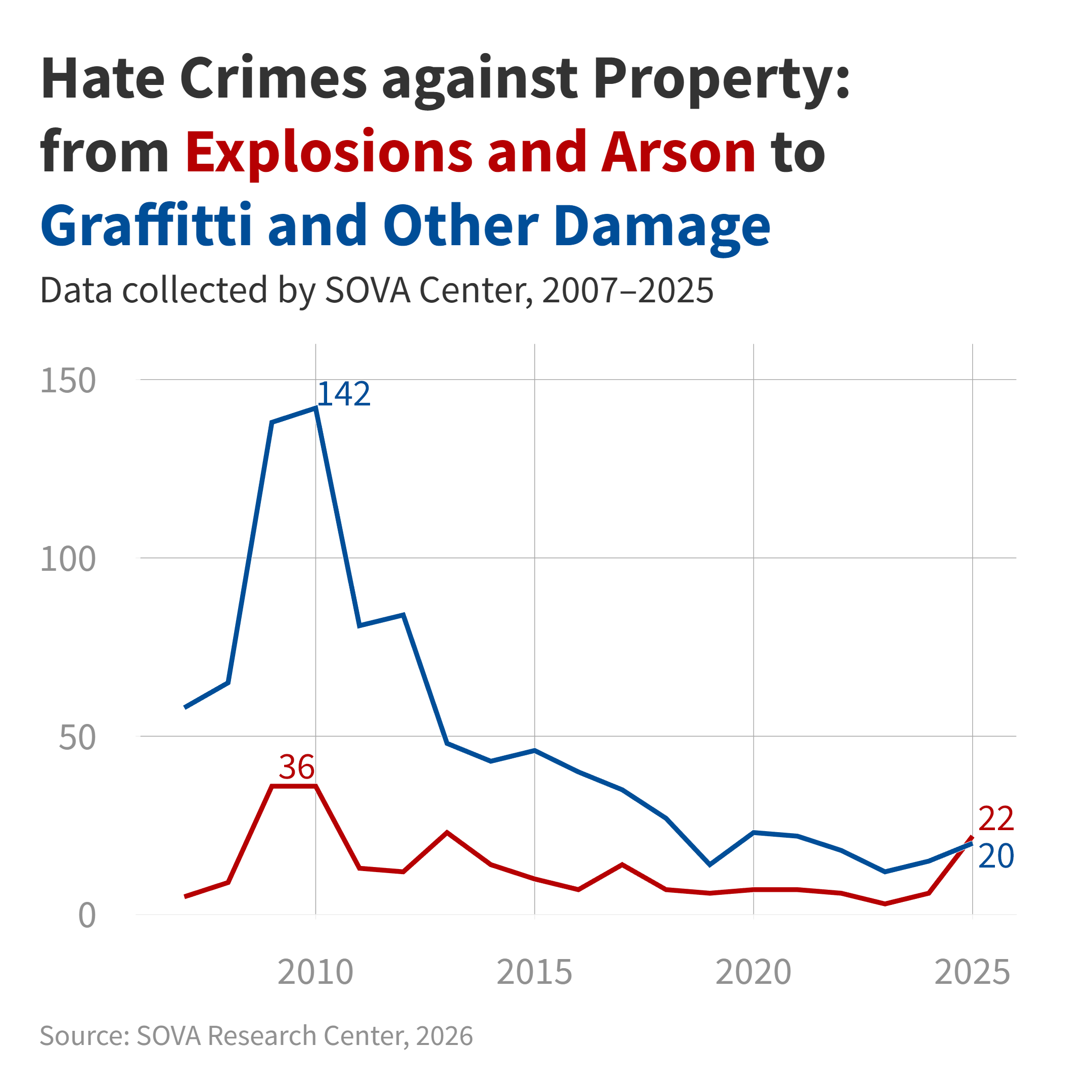

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites, and other property. The Criminal Code classifies these incidents under different articles, but law enforcement practice has not been consistent. Such actions are usually called vandalism, but for several years, we have preferred to avoid the term, since the term “vandalism,” both in the Criminal Code and in everyday usage, clearly does not capture all possible forms of attacks on material objects.

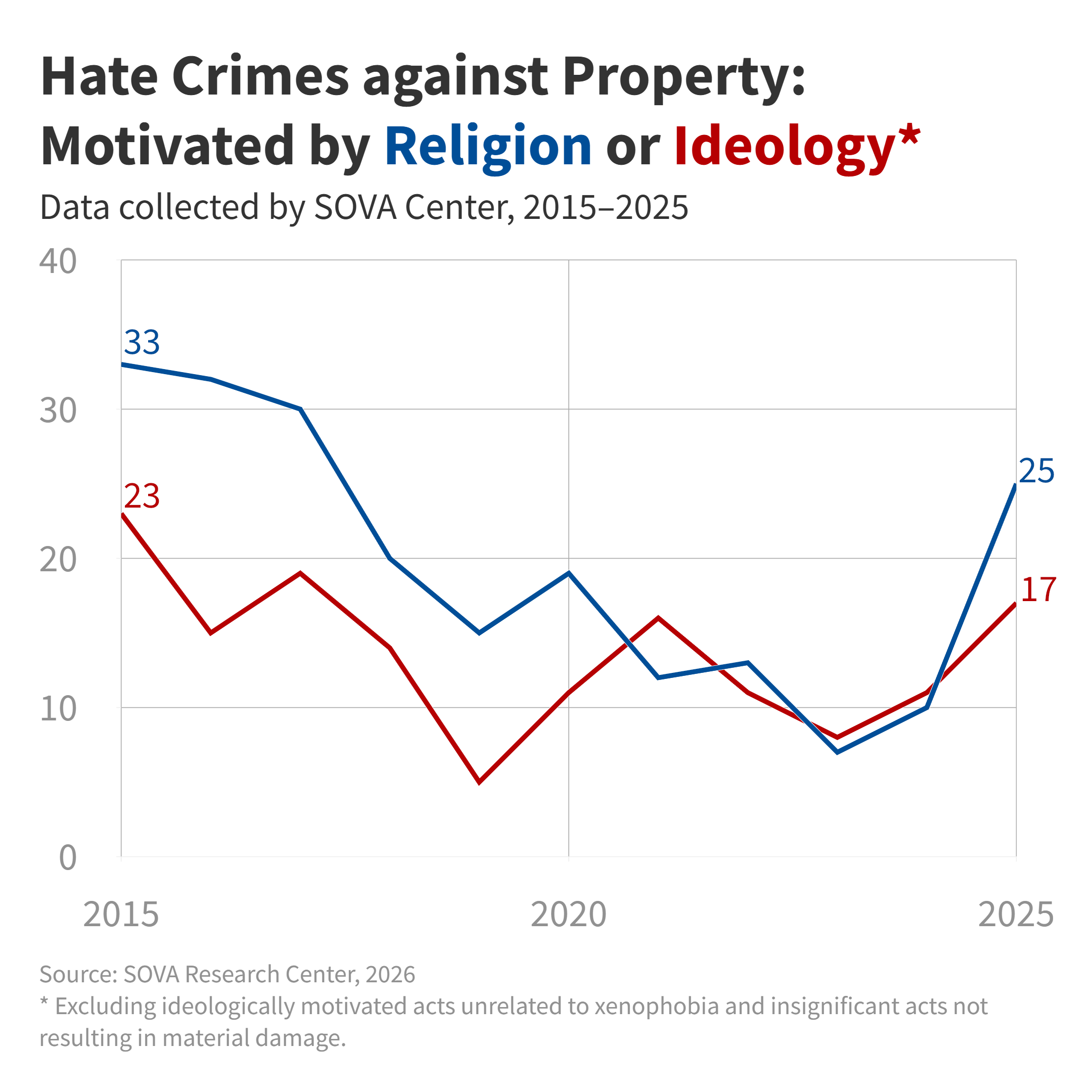

The number of property crimes motivated by religious, ethnic, or ideological hatred tracked by SOVA Center rose sharply in 2025. We learned of 42 cases in at least 18 regions of the country. In 2024, we recorded 21 cases in at least 10 regions.[21]

As with violent crimes, our counts do not include attacks on material objects committed for political or ideological reasons (and since 2022, such episodes have become especially numerous), except for the cases where those ideological reasons are connected to xenophobia. Also excluded from this chapter are actions that were classified as attacks on material objects but caused no material damage whatsoever.

Similarly, our statistics do not include minor incidents, including those committed by far-right activists, such as slashing tires, smashing windows of cars with North Caucasus license plates, or vehicles with Arabic stickers. We do not include isolated neo-Nazi graffiti or drawings on houses and fences, but we do include serial graffiti.

According to SOVA’s data, more than half of the attacks committed in 2025 (59%) targeted religious sites. There were 25 such incidents in 2025 vs. 10 in 2024. The majority (15 episodes vs. four in 2024 involved desecration of Muslim sites. Next were the Protestant sites with four incidents (vs. zero in 2024), followed by Orthodox (three attacks in 2025; five in 2024) and Jewish (three attacks in 2025; one in 2024).

Seventeen objects were seriously damaged based on ideological criteria (including hostility towards ethnic groups) rather than religion, exceeding the number of such attacks in the previous year (11 incidents). These objects included a World War II memorial, a Lenin monument, Victory Banners, and a police vehicle. This category also included the arson attack against the Tandoor Lavash bakery, attacks against the homes of Roma and people from the Caucasus, attacks on construction barracks housing Central Asian migrant workers, and the arson of a homeless shelter in St. Petersburg.

The number of the most dangerous acts, i.e. arson and explosions, rose sharply to one explosion and 21 cases of arson (vs. one explosion and five cases of arson the year before). The share of such acts was 52% (vs. 28% in 2024).

The regional distribution has also changed. In 2025, we recorded such crimes in 14 new regions (vs. five in the preceding year). At the same time, six regions that appeared in 2024 did not appear in our statistics this year.

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

When discussing prosecutions for hate crimes in this and the next chapter, unlike in the previous two chapters, we rely not on our own definition of what falls within the scope of monitoring and research, but on the courts’ interpretation. This means, first of all, that our counts include only the verdicts that recognized a hate motive, although hate crimes can definitely result in convictions where the motive of hatred was either not included in prosecutorial charges or not affirmed by the court. Next, while the counts in our previous chapters excluded ideologically motivated acts if their motive was not related to xenophobia, the chapters on law enforcement do include such verdicts. However, they will be noted separately.

In 2025, the number of people we know to have been convicted of violent hate crimes more than doubled compared to the year before (in 2024, the number had exactly doubled). In 16 regions, at least 41 verdicts were issued in which courts recognized a hate motive. In these cases, 187 people were convicted (vs. 73 people in 15 regions in 2024).[22]

Official statistics on verdicts involving a hate motive are unavailable because this qualifying element rarely appears as a separate part of a Criminal Code article, and the Supreme Court’s published verdict statistics include article parts but not the specific clauses within those parts.

In 2025, racist violence was typically qualified under the following Criminal Code provisions, which include a hate motive as an aggravating/qualifying element:

- “Attempted murder” (Article 30 Part 3 and paragraph “k” of Article 105 Part 2): one person;

- “Intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm” (paragraph “f” of Article 111 Part 2): one person;

- “Intentional infliction of minor bodily harm” (paragraph “b” of Article 115 Part 2): one person;

- “Battery” (Article 11 Part 2): one person;

- “Torture” (Clause “h,” Article 117 Part 2): one person;

- “Hooliganism” (Article 213 Part 2): 78 people;

- “Participation in mass riots” (Article 212 Part 2): 99 people;

- “Incitement of national hatred with the use of violence” (Article 282 Part 2): two people.

As our data shows, two people were convicted for violent crimes in 2025 under Article 282 (incitement of hatred), while only one such verdict was reported in the preceding year. One convicted offender was the above-mentioned teenager from Stavropol Krai, convicted for attacking a Roma child; the other was serviceman Amyrak Samaаn, convicted for xenophobic attacks against his ethnic Russian fellow soldiers.[23] Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation No. 11 “On Judicial Practice in Criminal Cases Involving Extremist Offenses,” of June 28, 2011[24] states that Article 282 may be applied to violent crimes if they are aimed at inciting hatred among third parties – for example, in the case of a public, demonstrative, ideologically motivated attack. In both cases discussed here, the attacks were public.

53% of those convicted in 2025 (99 individuals) were participants in the anti-Semitic riots at Makhachkala airport in October 2023.[25] Their share was even slightly larger than the year before. Courts in Stavropol Krai spent the entire past year handing down sentences under Article 212 Part 2 (participation in mass riots motivated by hatred).[26] On July 18, 2025, the Investigative Committee reported that a total of 28 verdicts against 135 defendants were issued for participating in the airport riots.[27] We were able to find information on 27 verdicts against 133 people.

Sentences for violent acts (sometimes combined with other charges) were distributed as follows:

- one person was sentenced to life imprisonment;

- five people – to over 20 years of imprisonment;

- 16 people – to terms of imprisonment ranging from 10 to 15 years;[28]

- 85 people – to terms of imprisonment ranging from 5 to 10 years;

- 19 people – to terms of imprisonment ranging from 3 to 5 years;

- five people – to terms of imprisonment up to 3 years;

- 40 people received suspended sentences of varying lengths;

- six people were sentenced to compulsory labor;

- one person – to community service;

- one person – to restriction of liberty.

Sentences imposed on eight defendants are unknown.

As we can see, the majority of those convicted in 2025 received lengthy incarceration sentences. The highest-profile verdict was issued in Moscow against members of the revived NS/WP group, who faced charges for a string of attacks on various people and objects, as well as the planned assassination of state television presenter Vladimir Solovyov. The group’s organizer, Andrei “Bloodman” Pronsky, received a life sentence; the others received terms ranging from 12 to 28 years behind bars.[29]

Members of other far-right groups were also sentenced to incarceration: participants in a teenage gang from St. Petersburg for attacks on passers-by; far-right activists in Krasnoyarsk for attacks on anti-fascists; and a group from Rostov-on-Don for attacks on people of “non-Slavic appearance.” Members of a St. Petersburg group (the so-called Tural gang), who called for violence against Russians and Uzbeks, practiced such violence, filmed their attacks, and published the videos on the Telegram channel Life of a Tramp (Zhizn Brodyagi), also received real terms of imprisonment.

21% of those convicted received suspended sentences. The share of suspended sentences for violent hate crimes increased compared to the previous year, when it constituted 6% (vs. 37% in 2023). Suspended sentences were issued primarily for less serious attacks involving pepper spray: against anti-fascists in St. Petersburg (mostly in the San-Galli Garden and mostly based on charges under Article 213) and in Ulyanovsk; against migrants in Kursk and Orenburg; against a Black person in Moscow. Many teenagers also received suspended sentences, including for the attack against a Roma child in Stavropol Krai, as well as a Krasnoyarsk group that attacked another group they mistook for Nazi skinheads.[30]

We have concerns regarding the lenient sentence imposed on far-right activists in Rybinsk of the Yaroslavl Region. For three attacks, including one against Communist Party member Ruslan Radula, “with the use of violence and an object used as a weapon, by a group of persons acting in prior conspiracy,” six neo-Nazis were sentenced just to community service.

Unfortunately, we were unable to find information about the penalty imposed on eight members of a far-right community in the Vladimir Region for several attacks on passers-by.

In 2025, according to our incomplete data, new criminal cases for ideologically motivated violence were initiated against 72 people (vs. 67 in 2024).

A notable case involved three teenagers from Yoshkar-Ola charged for attacking foreigners and a local resident in the spring of 2024, as well as for setting a car decorated with pro-government patriotic symbols on fire. One of the defendants, according to investigators, joined the terrorist organization banned in Russia known as Maniacs. Murder Cult (Manyaki. Kult Ubiystv, MKU).[31]

Last year, law enforcement continued its practice of investigating killings committed more than 10 and even 20 years ago.[32] In April 2025, Maxim Andreev and Vasily Volkov were arrested on charges of committing a xenophobic murder of a taxi driver in 2013. According to law enforcement, one of the defendants approached the authorities more than 10 years later, explaining that “for a long time now he has been tormented by pangs of conscience over what he did.”[33]

In December 2025, in St. Petersburg, 42-year-old Sergei Netronin was detained as a suspect in the murder of South Korean citizen Kim Hyon Ik back in December 2003.[34] This killing was part of a series of murders in the case of the notorious Combat Terrorist Organization (Boyevaya terroristicheskaya organizatsiya, BTO; the Borovikov-Voevodin gang), active in the 2000s.

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

As in the case of violent hate crimes, we cannot rely on official data, as the statistics of sentences published by the Supreme Court do not allow us to isolate the data we need. For example, in Article 244 CC (desecration of burial sites / cemetery vandalism), the hate motive is a paragraph, and paragraphs are not shown in the Supreme Court statistics separately. In Article 214 CC (vandalism), by contrast, Part 2 is not divided into paragraphs, but it covers both hate-motivated acts and any other acts committed by a group, so these two qualifying factors are not separated in the statistics.

There is an additional complication for property crimes. In today’s Russia, the Criminal Code contains not only offenses formulated specifically as hate crimes (i.e., ordinary crimes motivated by ideology), but also offenses that do not mention motive at all, yet are written in such a way that they can be described as ideological legal constructs. These norms place material objects targeted by the offense into a specially protected category based on their ideological importance, so the perpetrator’s motive becomes irrelevant. “Memorial structures or objects perpetuating the memory of those killed defending the Fatherland”, protected by Article 2434 CC, provide an obvious example. Quantitatively, however, the most prominent such category is formed by certain elements of Article 3541 CC. Although the article is titled “Rehabilitation of Nazism,” its provisions cover a wide range of acts. Some of them are related to historical memory and discussion. Others are, in fact, ordinary crimes, but the definition of Article 3541 CC essentially equates them to ideologically motivated crimes. These include attacks on various explicitly protected symbols, which may be present in the form of material objects. In practice, these most often – but not exclusively – involve the Eternal Flame or the St. George ribbon.

In this report, for the first time, we combine criminal law enforcement under both types of provisions aimed at protecting material objects: those that fit the definition of hate crimes, and those we regard as ideologically constructed. We also include verdicts for attacks on property that, for whatever reason, were qualified under articles dealing with public statements or other provisions (hooliganism, for example). At the same time, we do not include verdicts issued under articles on terrorism and sabotage. Although the line between subversive acts and vandalism is not always easy to draw, law enforcement clearly treats these legal qualifications as substantially different, which is evident, among other things, from the differing penalties provided under the respective CC articles.

In total, we know of 53 verdicts against 75 defendants for the above-described crimes against property in 2025 (we reported 38 verdicts and 47 convicted persons in 2024). Three additional individuals were referred for compulsory psychiatric treatment, two were subjected to coercive disciplinary measures, and one received a court fine with no conviction.[35]

In 2025, offenders were convicted for damaging material objects[36] under the following Criminal Code articles:[37]

- Article 148 Part 2 (insulting the religious feelings of believers committed in places specifically intended for worship) was utilized against four people in one verdict, and it was the only article in that verdict;

- Article 167 Part 2 (intentional destruction or damage of property) was used against eight people (vs. four such convictions in 2024). Only in one case did this constitute the sole article used by the prosecution, while in the remaining cases it was far from the principal charge;

- Clause “e” of Article 2073 Part 2 (so-called “war fakes” motivated by hatred) was utilized against one person; the very same act was qualified both under this provision and Article 214 Part 2;

- Clause “b” of Article 213 Part 1 (hooliganism motivated by hatred) was utilized against one person, and it was the only article in the verdict;

- Article 214 Part 2 (vandalism motivated by hatred) was used against 14 defendants (vs. 22 individuals in 2024). It was the only article for four of them;

- Clause “b,” Article 244 Part 2 (desecration of bodies of the deceased and their burial places) was utilized against one person in combination with other articles;

- Article 3541 Parts 3 and 4 (desecration of a symbol of Russia’s military glory; insulting the memory of defenders of the Fatherland) was used against 47 people (we knew of only 19 in 2024). It was the only charge for 39 of them.

Next, we examine the convictions, grouped into the following categories according to the targets of the actions in question:

- expressing ethnic xenophobia;

- related to religion;

- “attacks on traditional Russian values”;

- related to events in Ukraine;

- other acts directed against the authorities.

A single verdict may combine acts from more than one category, but only a few such cases appear among those examined in this chapter.

49 people were convicted for acts we can describe as attacks on “traditional values.” In the overwhelming majority of cases, they faced sanctions for desecrating symbols of military glory – the Eternal Flame and sometimes the St. George ribbon. Accordingly, the overwhelming majority of verdicts (for 44 defendants) were issued under Parts 3 and 4 of Article 3541 CC. Four additional defendants faced sanctions under Article 148, and one each – under Articles 214 and 244.

In virtually all of these cases, we consider the verdicts inappropriate.[38] In our opinion, criminal prosecution is justified only where an act poses a substantial public danger. We found no such danger in the acts of at least 47 of the 49 people – their actions either caused no damage whatsoever to monuments or other objects, or the damage was negligible.[39] In some cases, the actions in question involved insults to the religious or patriotic feelings of presumed witnesses, whether online or offline; however, we do not consider offended feelings a sufficient basis for criminal prosecution.

Nine people faced sanctions for damaging material objects with the motive of ethnic xenophobia. The acts range from graffiti on a supermarket wall to arson attacks on market stalls, cars,[40] or migrants’ homes.

Two people faced sanctions for damaging objects on the grounds of religious xenophobia: one for writing “ĀYAH 9:5”[41] on an arch near the Church of St. Blessed Xenia of St. Petersburg, and the other for setting fire to the Church of St. Dmitry Donskoy in Tyumen.

Thirteen people faced sanctions for acts connected to the armed conflict with Ukraine. The articles related to property damage were never the only charges in these verdicts. Acts interpreted as vandalism included arson attacks against the cars or homes of servicemen, as well as cars bearing “Z” stickers; they also included the posting of leaflets of the Freedom of Russia Legion (recognized as a terrorist organization) at a cemetery where participants in the armed conflict with Ukraine are buried. We consider four verdicts in this group inappropriate.

Four people faced sanctions for acts motivated by hostility towards the authorities and not directly linked to Ukraine, ranging from damaging police vehicles to arson attacks on government buildings. We consider one such verdict inappropriate.

Sentences for attacks on material objects (often combined with other charges) were distributed as follows:

- one person was sentenced to life imprisonment;[42]

- 35 people were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment;

- six defendants received suspended sentences;

- five defendants were sentenced to corrective labor;

- eight defendants – to community service;

- three defendants – to compulsory labor;

- five defendants – to restriction of liberty;

- nine defendants – to fines.

Sentences issues against three defendants remained unknown to us.

In all cases, courts ordered convicted offenders to pay monetary compensation for the material damage they caused.

As shown by the data above, approximately half of the defendants were sentenced to imprisonment for varying terms. However, for roughly half of these convicts, the charges related to attacks on material objects were not the only ones and far from the most serious in the verdicts; they were accompanied by charges such as robbery, terrorism, treason, and so on. For example, in the aforementioned case of the neo-Nazi NS/WP group, the article related to property damage was used to qualify arson attacks on cars and police stations. Two people were sentenced to imprisonment, taking into account their previously imposed sentences.

The presence of additional charges in some verdicts precludes an adequate comparison of sentencing severity across the categories listed above. For instance, in cases related to the conflict in Ukraine, multiple (often grave) charges were present in every verdict involving real imprisonment.

Overall, 18 out of 36 people were sentenced to imprisonment solely for desecration of objects or damage to property with no additional charges.

A resident of Tyumen was sentenced to two years in a settlement colony under a combination of Article 167 (attempted intentional destruction of another’s property by arson) and Article 214 Part 2 for setting fire to the Church of St. Dmitry Donskoy. The harshness of the sentence likely stems from the gravity of the act. All other defendants sentenced to imprisonment for damaging material objects, absent the above circumstances, were convicted under Article 3541. In their cases, we consider imprisonment clearly excessive.

For example, an army conscript in the Kaliningrad Region was sentenced under Article 3541 Part 4 to one and a half years in a settlement colony. Together with a fellow serviceman, he tore down from the wall of a school building in the settlement of Yantarny a St. George ribbon flag dedicated to the Victory Day, damaged the fabric, shouted slogans “justifying Nazism,” and performed a fascist salute.[43]

We consider the remaining incarceration sentences under this article to be not only excessively harsh but also clearly inappropriate. These verdicts involved charges such as damaging a Victory Day display stand or stepping on a poster featuring the St. George ribbon. Seventeen people were sentenced to incarceration solely for desecrating the Eternal Flame: they lit cigarettes from the flame, dried and warmed their shoes or feet nearby, danced, threw small objects into the fire, cooked food over it, and one person urinated into the flame.

In assessing the appropriateness of verdicts issued for attacks on material objects, we base our conclusions not only on the proportionality of restrictions on freedom of conduct and civil liberties, but also on two additional considerations. First, ideologically motivated offenses incur harsher punishment than ordinary ones. Therefore, if we believe that the convicted offender was not, in fact, guided by ideological motives, we classify the case as inappropriate. Second, political or ideological hostility per se is not criminalized. Accordingly, where an attack on a material object is motivated by political or ideological views unconnected to the propaganda of violence or xenophobia, the act is essentially a form of political criticism. As such, it should be treated as ordinary vandalism, without the aggravating “hate motive,” and punished in proportion to the actual damage caused.

Overall, we consider the convictions of 10 individuals to have been appropriate (vs. four the year before) and those of 49 individuals to have been inappropriate (vs. 35 the year before). In five cases, we are not sure (vs. one the year before), and in one case, we are unable to pronounce a judgment on appropriateness (vs. three the year before). We classified the verdicts against 11 individuals as “other” (compared with six in 2024).

Of the 49 inappropriately convicted, almost everyone – 44 people – faced sanctions for attacks on “traditional values” (in 2024, there were only 15 such cases; another 11 involved acts related to Ukraine, and nine involved other acts against the regime).

We are aware of 44 new criminal cases against 67 people initiated in 2025 for attacks on material objects similar to those discussed in this chapter (some of which have already resulted in verdicts). This figure is roughly comparable to what we reported for 2024 – 47 cases against 66 people – but we will inevitably receive additional information on cases initiated over the past year.

[1] Refers to the desecration (real or alleged) of ideologically significant symbols, primarily those connected to military history: the Eternal Flame, the St. George ribbon, and so on.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. (2009). https://www.osce.org/odihr/36426 ; Verkhovsky, A. (2015). Criminal Law in OSCE Participating States on Hate Crimes, Incitement to Hatred, and Hate Speech (2nd ed., rev. & expanded). SOVA Center. http://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/cl15-text.pdf.

[3] Database: Acts of violence, SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/database/violence/). Here and throughout, all the numbers are as of 2026, January 14.

[4] Yudina N. Neo-Nazis on the Rise: Hate Crimes and Countering Them in Russia in 2024, SOVA Center. 2025. February 28 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2025/02/d47102/).

[5] Moreover, we do not include four Ukrainian regions brought under Russian jurisdiction in the autumn of 2023. Crimea is included, however, because in recent years the regime there has differed little from that in Russia’s southern regions.

[6] Here and throughout, all chart data is based on the monitoring results of SOVA Center.

[7] At that time, court proceedings against them were underway and ended with verdicts in 2025.

[8] NS/WP (National Socialism / White Power) has been designated a terrorist organization in Russia.

[9] In a similar report the year before, we wrote of 19 regions.

[10] Neo-Nazi teenager attacks school in Odintsovo: 10-year-old boy killed, SOVA Center. 2025, December 16 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2025/12/d52788/, in Russian).

[11] Links to nationalist pages found on the phone of a teenager detained for murder, Moskovsky Komsomolets. 2025, April 9 (https://www.mk.ru/incident/2025/04/09/v-telefone-podrostka-zaderzhannogo-za-ubiystvo-nashli-ssylki-na-stranicy-s-nacionalisticheskim-uklonom.html, in Russian).

[12] More on this: Alperovich V. Nationalists on the Path of Success:Public Activity of Far-Right Groups, Winter–Spring 2025, SOVA Center. July 29 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2025/07/d52000/ , in Russian).

[13] The idea of the “white wagon” gained popularity among the far right in the early 2000s. Participants in these actions carried out attack raids on commuter trains or subways, searching for people of “non-Slavic appearance,” beating them up, and filming their actions on camera.

[14] SOVA Center counts only those incidents known to us in which we see a deliberate attack motivated by hatred.

[15] For more on the reasons behind attacks on homeless people, see, for example: Alperovich V., Yudina N. The Ultra-Right on the Streets with a Pro-Democracy Poster in Their Hands or a Knife in Their Pocket: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2012, SOVA Center. 2013. April 26 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2013/04/d26972/).

[16] Posts on far-right platforms claiming that the business of transporting, storing, and distributing drugs is mainly carried out by people from Central Asia, Africa, and Roma communities raise the level of hatred even further.

[17] Primarily from videos posted by far-right groups.

[18] Numbers for this particular group of victims have increased significantly compared to what we reported in a similar report the year before (as of February 8, 2025, we wrote about 14 victims). The peak of such attacks occurred in 2007 (seven killed, 118 injured); since then, there has been a steady decline. Since 2013, the trend has been unstable.

[19] On January 19, the anniversary of the murder of lawyer Stanislav Markelov and journalist Anastasia Baburova, memorial events for victims of neo-Nazis were held in 37 cities in Russia and abroad. In Russia, actions took place in 29 cities. For more details, see: Russian Nationalism and Xenophobia in January 2025, SOVA Center. 2025. February 7 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/news-releases/2025/02/d47101/).

[20] For more details: Founder of Male State issues threats against a doctor at a private clinic in Moscow, SOVA Center. 2025, July 11 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2025/07/d51894/, in Russian).

[21] Database: Vandalism, SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/database/vandalism/).

[22] Database: Sentences, SOVA Center (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/database/sentences/).

[23] Military is highly isolated from outside observers, so cases of violence with a xenophobic motive arising from hazing within the armed forces rarely become public.

[24] Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation No. 11 “On Judicial Practice in Criminal Cases Concerning Crimes of an Extremist Nature,” Supreme Court of the Russian Federation (https://www.vsrf.ru/documents/own/8255/, in Russian).

[25] For more details, see: Anti-Semitic actions in the North Caucasus, SOVA Center. 2023, October 31 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2023/10/d48837/, in Russian).

[26] Also sentenced under Article 2631 Part 3 CC (failure to comply with transport security requirements at transport infrastructure facilities and on vehicles, where this act negligently resulted in major damage, committed by a group of persons acting in prior conspiracy).

[27] Sentences issued against 135 defendants in the criminal case over the riots at Makhachkala airport, Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, [Telegram post]. 2025, July 18 (https://t.me/sledcom_press/22738, in Russian).

[28] All for participation in the Makhachkala airport riot.

[29] For more details, see: Verdict handed down in the NS/WP case, SOVA Center. 2025, December 19 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2025/12/d52810/, in Russian).

[30] The teenagers were found guilty under Article 213 Part 2 CC (hooliganism committed with the use of violence against citizens, motivated by hatred or hostility towards a social group, committed with the use of objects employed as weapons, by a group of persons). We believe that in this case, a motive of political and ideological hatred would be more appropriate than hatred towards the “Nazi skinheads” social group. In our view, this motive can be applied as an aggravating circumstance for serious offenses. Thus, we do not consider the verdicts for an attack motivated by hatred towards the group “Nazi skinheads” to be inappropriate, but we do view this legal qualification as erroneous. See: In St. Petersburg, nationalists are recognized as a social group, SOVA Center. 2011, February 14 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/other-actions/2011/02/d20981/, in Russian).

[31] Supreme Court designates MKU a terrorist organization, SOVA Center. 2023, January 16 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2023/01/d47493/).

[32] We first observed this trend in 2020. See: Yudina N. “Potius sero, quam nunquam”: Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2020, SOVA Center. 2021, February 5 (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2021/02/d43611/).

[33] The court selects preventive measures for defendants in a murder case committed in 2013, Moscow Courts of General Jurisdiction [Telegram post]. 2025, April 17 (https://t.me/moscowcourts/6425, in Russian).

[34] Verdict handed down in St. Petersburg in the Borovikov-Voevodin gang case, SOVA Center. 2011, June 14 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2011/06/d21872/, in Russian).

[35] We do not take into account the verdicts if we have no substantive information about the cases (beyond the fact that certain individuals were convicted under specific CC articles).

[36] Individuals who were released from liability, referred for compulsory treatment, had cases dismissed with the imposition of a court fine, and so on, are not included here.

[37] Strictly speaking, the list of articles provided below is not exhaustive. Ideologically motivated attacks on material objects may sometimes be qualified under other CC articles, not generally monitored by SOVA Center. For example, in 2025, we know of verdicts that involved Article 2434 (destruction, damage, or desecration of military graves or monuments dedicated to the defenders of the Fatherland) and Article 329 (desecration of the state coat of arms or state flag of Russia).

[38] Our method for determining the appropriateness of verdicts is as follows. We classify a verdict as appropriate if we believe that the act was connected to xenophobia and that the punishment was generally justified. A verdict is considered inappropriate if the action did not merit criminal prosecution – for example, if the charges were unfounded, the legal provision itself is unconstitutional, or the danger posed by the imputed act was clearly insignificant. If the charges were generally justified but unrelated to countering xenophobia, we classify the verdict as “other.” If, for any reason, we cannot evaluate a case unambiguously, we categorize it as “not sure.” In some instances, we must simply conclude that we “do not know.”

[39] Essentially, this often amounts to nothing more than disorderly conduct falling under Article 20.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO). In addition, the “desecration” of structures generally falls under Article 214 CC on vandalism, which provides for sanctions less severe than those under Article 3541 CC. Moreover, if the damage caused by unlawful actions is insignificant, cases under Article 214 can also be dismissed due to the trivial nature of the offense. For borderline cases, it might be helpful to introduce an article similar to Article 7.17 CAO covering the destruction or damage of other people's property or to clarify the existing article by adding vandalism that did not cause major damage.

[40] Including a car decorated with a Buddhist mantra in Tibetan, which the perpetrator mistook for a Quran quotation in Arabic

[41] A verse from the Quran that calls for the persecution of polytheists.

[42] The already mentioned leader of NS/WP, whose verdict also included property damage charges.

[43] The second defendant in the case was also sentenced to a settlement colony, but his verdict included other charges as well.