Summary

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence : Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders” : Attacks against the LGBT : Attacks against Ideological Opponents : Other Attacks

Crimes against Property

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

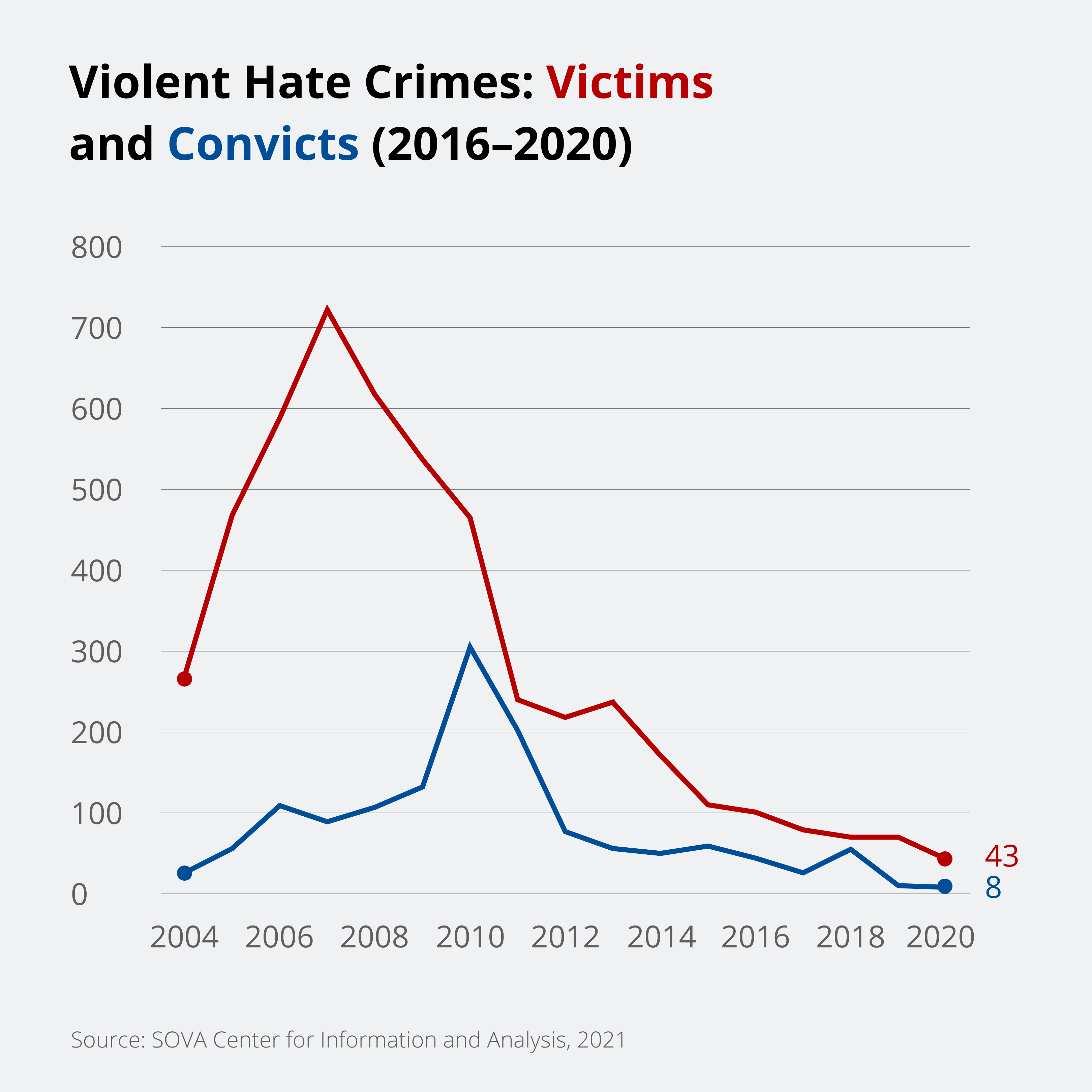

Crime and punishment statistics

This report by SOVA Center[1] is focused on the phenomenon of hate crimes, i.e. on ordinary criminal offenses that were committed on the grounds of ethnic, religious, or similar hostility or prejudice[2] and on the state’s counteraction to such crimes.

Summary

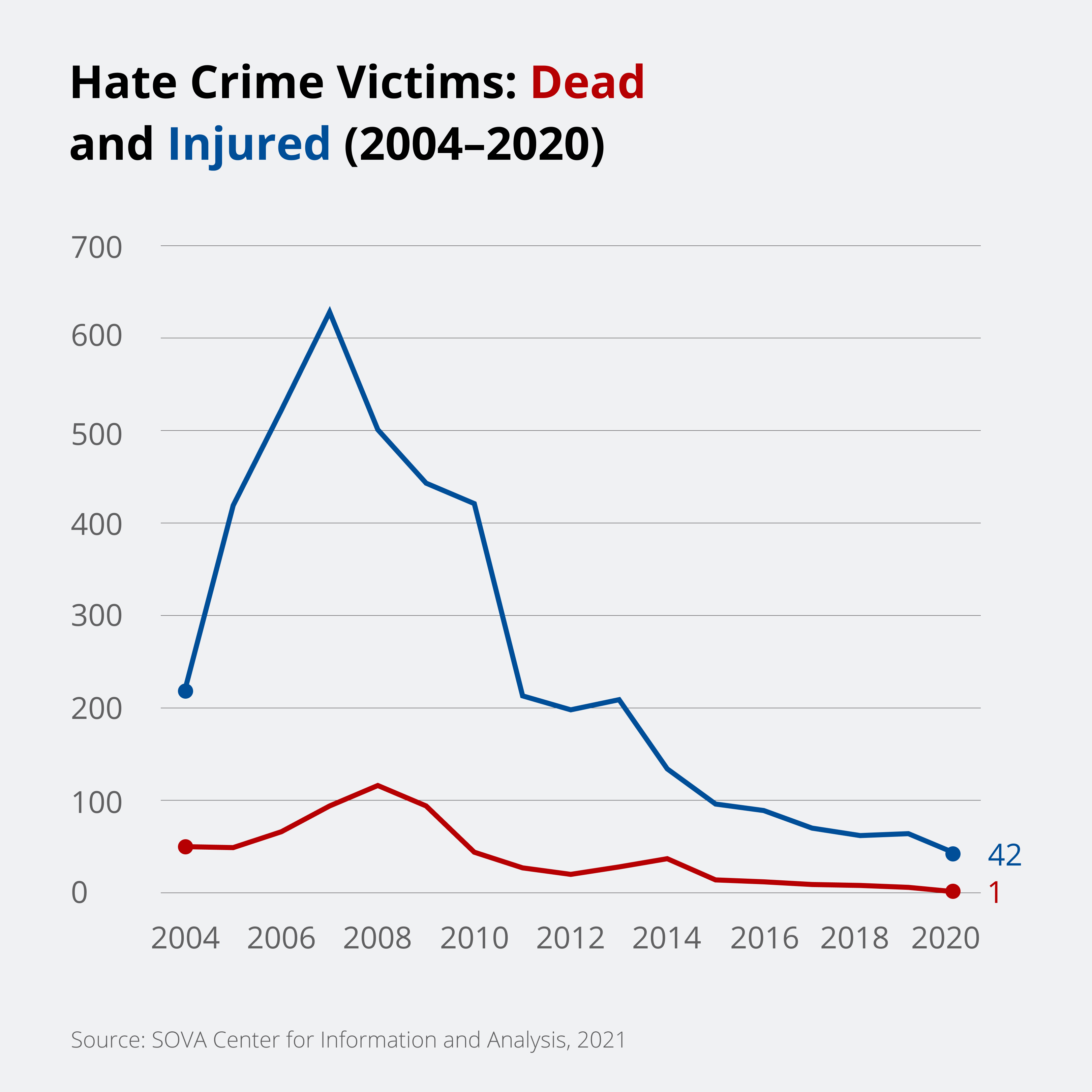

Despite the current events of a global scale – the coronavirus epidemic and the Black Lives Matter movement in America – that provoked the rise in xenophobic rhetoric on the Russian Internet, the number of xenophobically motivated attacks decreased in the past year, including the number of murders. Contrary to the fears of many, the war in Nagorno-Karabakh did not lead to an increase in clashes between the Armenians and the Azeris on Russian soil, although such clashes still occurred.

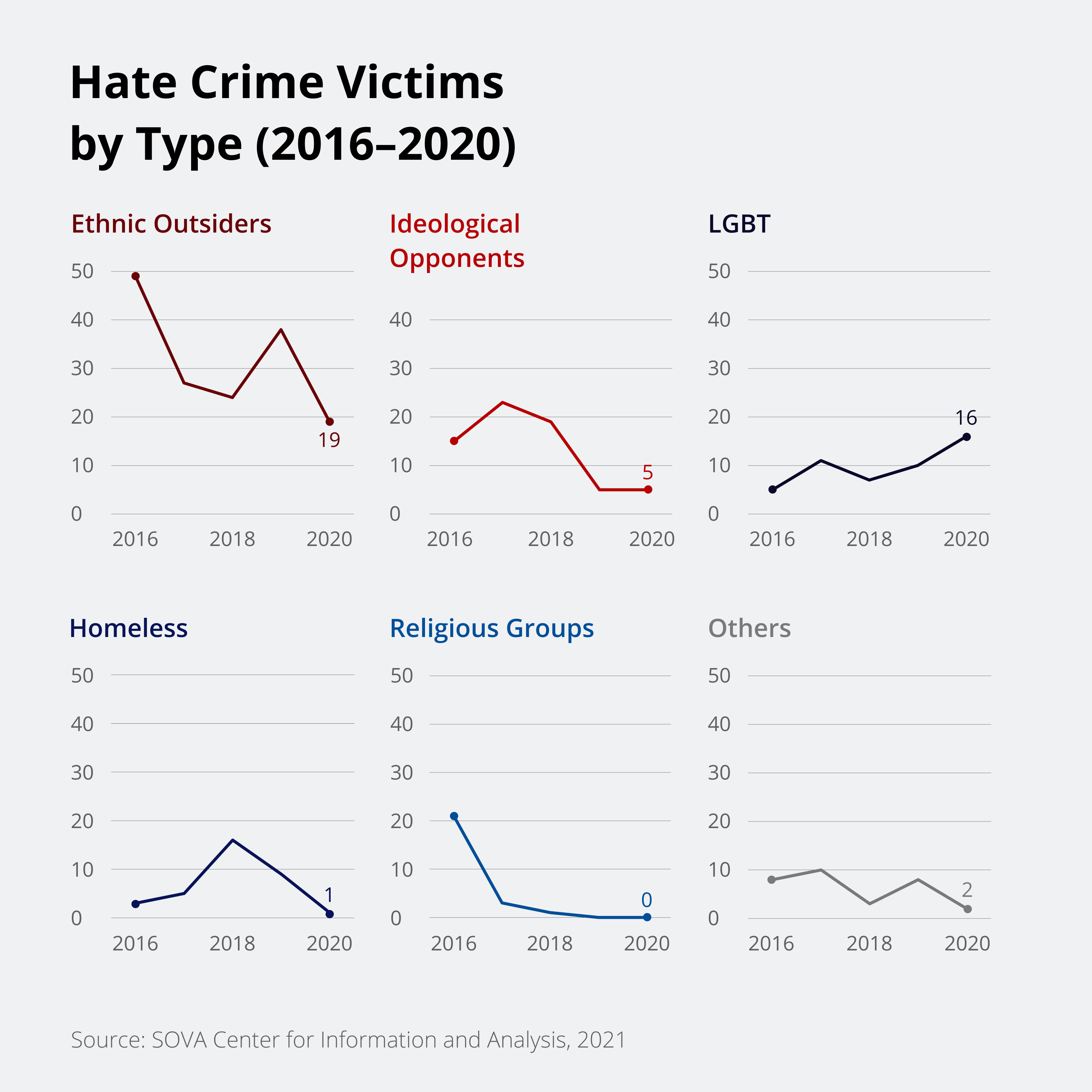

Typologically, “ethnic outsiders” remained the main victim group in 2020, although the number of victims in this group was lower than a year earlier. On the other hand, the number of victims from LGBT community and those deemed as such increased. In part, attacks on this group were provoked by the death of a popular neo-Nazi, the founder of the Occupy Pedophilay movement, Maxim (Tesak) Martsinkevich, in whose memory “anti-pedophile raids” were carried out in at least two regions. The number of attacks on “ideological opponents” also increased in 2020: the pro-Kremlin group SERB remained active, attacking opposition protests; SERB members were especially visible in summer at the protests at the Embassy of Belarus.

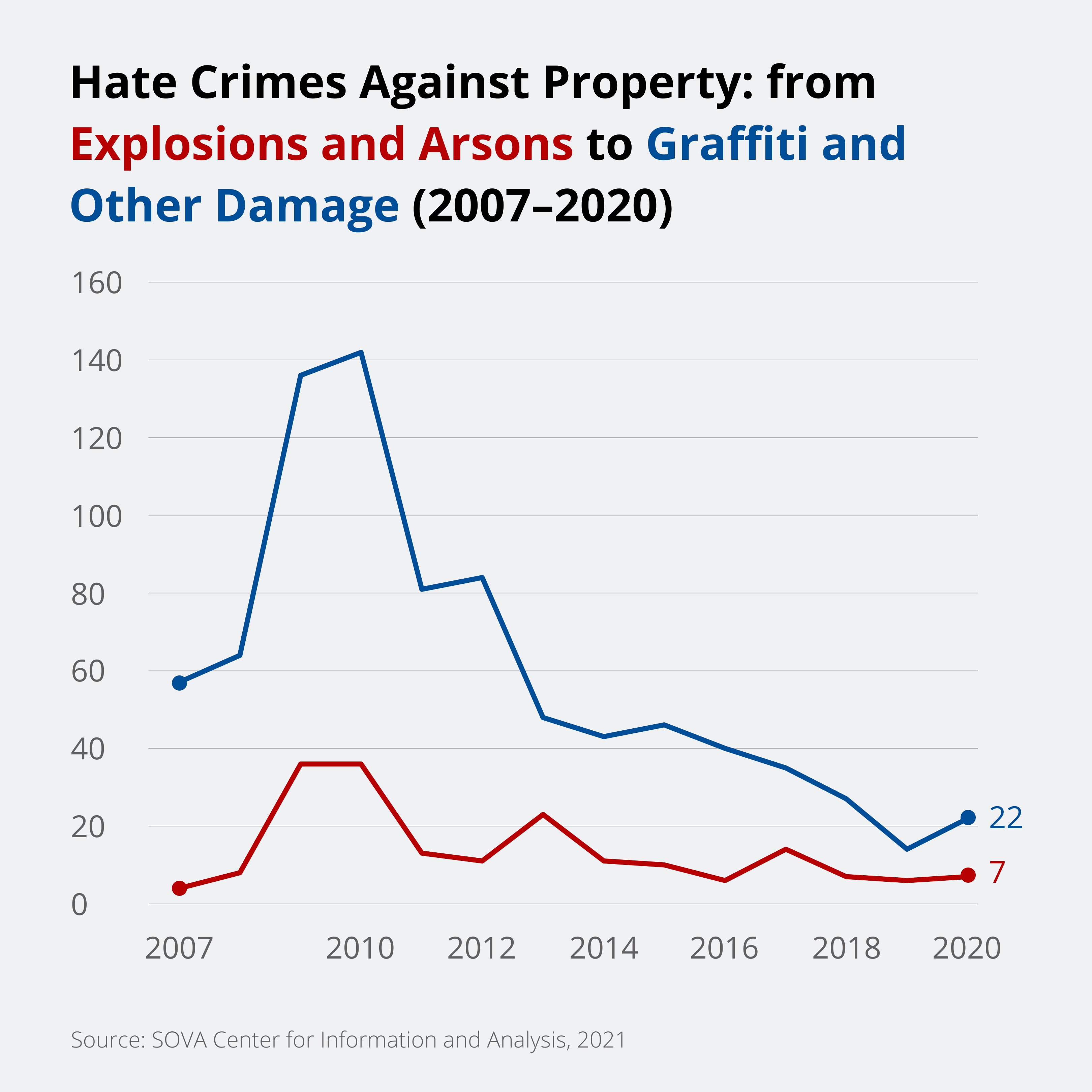

Instances of damage to buildings, monuments, cemeteries, and various cultural sites, motivated by religious, ethnic, or ideological hatred were more frequent than in 2019; both religious and ideological sites were affected. It is comforting that the proportion of dangerous acts – explosions and arson – has decreased in the past year.

The number of convictions for hate crimes remained about the same as the year before, while the number of convicted persons even decreased slightly. However, new high-profile and significant trials are upcoming: the year ended with the arrests for the murders committed in the 2000s of a whole group of members of neo-Nazi gangs that used to be well-known in the past, including one of the most popular leaders of the Moscow Nazi skinheads of the late 1990s, Semyon (Bus) Tokmakov.

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

In 2020, at least 43 people became victims of ideologically motivated violence; one of them died and the others were injured or beaten; five people received serious death threats. The total number of hate-motivated attacks is decreasing: in 2019, seven people died and 64 were injured or beaten[3]. However, our data is incomplete, especially for the year that just ended, and eventually the numbers will inevitably increase[4].

As usual, we do not report on the victims in the republics of the North Caucasus and Crimea, where our methods are, regrettably, not applicable. We cannot compare or refine the data we have collected with any other statistics on hate crimes in Russia, as no other statistics exist.

Our data is, unfortunately, only a partial reflection of the real picture, and does not reflect the true extent of the violence. And this statement is applicable throughout the entire time of our monitoring. In the last few years, online and offline media have been describing hate crimes in the manner that makes it impossible to determine whether they were motivated by hatred or have not been reporting them at all. It is extremely rare that the victims turn to human rights organizations, and hardly ever - to organizations that provide legal, medical, educational, or financial assistance, and it is often impossible to extract enough data from these appeals. Neither do the victims go to the police, since they do not really expect to get any help from police officers but instead are very much afraid of potential problems. The attackers, who merely a few years ago used to fearlessly publish videos of their “acts”, have become more cautious. And when such videos do appear, it is often not possible to verify their authenticity and establish the time and place of the attack.

As a result, in no way does our data reflect the true scope of what is happening. But since our methodology has not changed since the start of the data collection, we are able to analyze the dynamics.

In the past year, we have recorded attacks in 11 regions of the country (in 2019 – in 20 regions). Moscow (12 injured and beaten) and St.-Petersburg (20 injured and beaten) traditionally lead in terms of violence level. And this is a rare occasion in our history of data collection when more victims were recorded in St. Petersburg than in Moscow. Just like the year before, a significant number of victims (three) was reported in the Sverdlovsk region.

In the past year, assaults were reported in the regions where they have not been reported before, namely, in the Arkhangelsk, Kaluga, Novosibirsk, and Saratov regions. At the same time, however, a number of regions disappeared from the statistics: hate crimes were not recorded in Altai Krai, Primorsky Krai, Stavropol Krai, the Vologda, Nizhny Novgorod, and Rostov regions, and Sakha Republic (Yakutia).

According to our data, in the past ten years, in addition to Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the Moscow and Leningrad regions, crimes have been recorded practically annually in the Volgograd, Vologda, Voronezh, Kaluga, Kirov, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Rostov, Samara, Sverdlovsk, Rostov, and Tula regions, Primorsky Krai, Krasnodar Krai, and Khabarovsk Krai. However, it is also possible that the incident reporting is just better organized in these regions.

Attacks Against “Ethnic Outsiders”

Those perceived as “ethnic outsiders” by the attackers remain the largest group of victims, though their numbers are slightly lower compared to the previous year. In 2020, we recorded 19 ethnically motivated attacks, a bit lower than the 21 victims reported in 2019.

Victims in this category include natives of Central Asia (4 beaten, compared to 3 killed, 11 beaten in 2019) and Caucasus (1 killed, 8 beaten, compared to 1 beaten in 2019)[5]; individuals of unidentified “non-Slavic appearance” (2 beaten, compared to 3 beaten in 2019). The brutal murder in Volgograd stands out from the rest: on 13 June 2020, Timur Gavrilov, a 17-year-old medical student from Azerbaijan, died of 20 stab wounds. The murder suspect was a member of a far-right organization and attacked the student as he set out to “kill a non-Russian” that day.

In addition to these, a native of Buryatia was beaten at a train station in Yekaterinburg. The attacker did not like his “narrow eyes.”

The echo of the events related to the US Black Lives Matter movement has reached Russia. Fortunately, there were few direct attacks on black people, but still a bit more than a year earlier. We have information about at least 2 attacks in 2020 (between 2017 and 2019, there was 1 attack per year, in each 1 person was beaten). For example, in a subway car in St. Petersburg, a group of aggressive young men sprayed aerosol from a UDAR gas pistol in the direction of the natives of Africa and began to beat them. The level of intolerance towards black people in Russia is quite high, as has been clearly demonstrated by the regular and rather large-scale online racist campaigns. For example, on 8 June in Bryansk, a Yandex Taxi driver refused to take a black student Roy Ibonga and responded affirmatively when asked whether he was a racist. The video of the conversation was published in the VKontakte group Overheard in Bryansk and widely distributed on social media. After the scandal broke, Yandex Taxiremoved the driver and publicly condemned his behavior. However, the story did not end there: Kirill Kaminets, a blogger living in Germany, the author of Sputnik and Pogrom and the founder of the Vendee project, launched the hashtag #YandexCuckold on Twitter, asserting that Yandex Taxi had “infringed on the rights of Russian drivers and denied them the right to choose customers.” The hashtag was posted by many other users.

A mixed-race St. Petersburg resident and blogger Maria Magdalena Tunkara received regular racist threats in her blog; as proof, she shared screenshots of some of the threats she has been receiving, including references to “monkeys” and comments like “Negroes do not belong in Russia.” The blogger was insulted not only in the far-right social network groups and the Telegram channel of the founder of the group “Men’s State” Vladislav Pozdnyakov but also, for example, in the popular apolitical imageboard “2ch,” also known as “Dvach.” On the eve of the Without Borders Fest, the National Conservative Movement (NCD) reported that Maria Tunkara “insulted nationalists” and was planning on 20 June to speak at the festival organized by “leftists and feminists.” As a result, Tunkara was forced to cancel her participation in the event.

It's not just black people who face hate campaigns. In February 2020, the media reported that Elena Melnik, a resident of Kogalym in the Tyumen region, who tried to publicly stick up for her Chechen husband, who had been abducted in Grozny, received more than 100 xenophobic messages with threats and insults on the social network VKontakte over the course of just one night. She “was accused of causing the degeneration of the “Russian nation,” of betraying “the blue-eyed Slavic blood” and “the Russian traditions, for which our Orthodox grandfathers have been giving their lives for many centuries.” They called her a “stinking degenerate” and “a whore” and wrote that they would gladly cut her throat, etc.[6]

According to the results of the 2020 poll by the Levada Center[7], 44% of the Russian respondents supported the idea of not allowing the Roma into the country. And in the past year, we have seen anti-Roma riots. After a 16-year-old Roma driver hit a 15-year-old girl in one of the villages of Stavropol Krai on August 13, local residents came together for a gathering and demanded that the Roma community be evicted from the village. The ultra-right immediately took advantage of the situation and attempted to use “the Kondopoga method” to inflate the domestic conflict into an ethnic one; in right-wing Internet resources this news was published under the headline “I Hate Gypsies.”

In December, some excitement was caused by the 10th anniversary of the events on Manezhnaya Square in Moscow[8]. All the ceremonies were held online: memorial speeches were streamed online, and the evening in the memory of the killed Spartak fan Yegor Sviridov[9] was held in the VKontakte social network. However, on the eve of the anniversary, that is, on 6 December, a video of an attack on Dagestan natives by a “group of Russian nationalists” spread on the far-right Internet. According to the comments to the video, it was “in Yegor’s memory.”

Fear of the coronavirus has provoked an increase in xenophobic anti-migrant sentiment in the society. Numerous offensive and racist comments were posted on social media about Chinese people and nationals of other Asian countries. Fortunately, direct attacks did not materialize, probably due to the increased mobilization of the police, which is strictly monitoring quarantine compliance. However, the far-right was very active on the Internet. Since the end of winter, anti-migrant materials have been distributed on nationalist websites, telling about robberies and murders, “Gastarbeiter gangs” operating in various areas of Moscow, “pregnant Tajik women” with infections in maternity hospitals. Petitions appeared in far-right online resources demanding a tougher migration regime. The National Democratic Party (NDP) published a petition titled “Let Us Protect the Labor Market and the Security of Russian Citizens!” proposing to deport migrants who have lost their jobs and introduce a visa regime for the Central Asian countries. Konstantin Malofeev, a well-known Orthodox nationalist, also spoke out in support of the immediate deportation of all migrants left without work. And the Volgograd “Russian Corpus” organization promised to “put our vigilantes in the streets of our glorious city.”

Such vigilantes patrolling markets appeared in Yekaterinburg. Patrols arrived in the largest market known as Tagansky Row, located in the Seven Keys residential district, home to many Chinese, to “check for coronavirus” only Asian countries nationals. According to Ataman Gennady Kovalev of the Ural Cossacks non-profit partnership, similar groups were patrolling the streets of Ryazan and Tula[10].

The armed conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh has caused ethnic clashes between the Armenians and the Azeris on Russian soil. On 27 July 2020 in St. Petersburg, several Azerbaijani citizens attacked two Armenian citizens, shouting anti-Armenian slogans and recording it on video[11]. On 24 July, Moscow too saw clashes between natives of Armenia and Azerbaijan[12].

Attacks against the LGBT

The number of attacks against the LGBT community was, once again, higher than in the previous year. SOVA Center has recorded 16 beaten (in 2019 – 1 killed, 7 injured and beaten). It seems to us that the increase in the attacks on LGBT people is not accidental. On the one hand, it is connected with the high level of domestic homophobia in the Russian society, which is recorded by annual surveys. According to the results of the 2019 poll by the Levada Center[13], 56% of the respondents perceive LGBT people “mostly negatively.” In part, negative attitudes toward LGBT people were fueled by the authorities as the law passed in 2013 prohibited “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships” among minors. On the other hand, homophobic context has always been inherent in neo-Nazi movements (both during the Third Reich and among Russian neo-Nazis since the early 2000s), whose ideology is based on biological postulates and arguments about blood and soil.

In 2020, homophobic attacks were provoked by the death of a well-known neo-Nazi, the former leader of the far-right Restrukt movement and the founder of the Occupy Pedophilay movement Maxim (Tesak) Martsinkevich[14]. In October 2020, in Arkhangelsk, a group of young men held a “pedophile hunt” in his memory: posing as a minor, they met a man online and set up a sex date. The group showed up on the date with a video camera and recorded their interrogation of the man, whom they afterwards forced to drink urine[15]. According to Vladislav Pozdnyakov of “Men’s State”, the attack on the student of the Theater Institute Ilya Bondarenko near the Uzbechka restaurant in Saratov in December 2020 was also organized by the local far-right from Occupy Pedophilay, who “caught a pedophile.”[16]

The number of attacks targeting LGBT were added to by the attacks against those who were mistaken for LGBT. This happened, for example, in January 2020 in St. Petersburg, when attackers did not like a man’s appearance; or in Moscow, when the teenagers’ dyed hair aroused suspicion about their “non-traditional” sexual orientation.

Attacks against Ideological Opponents

In 2019, the number of attacks by the ultra-right against their political, ideological, or “stylistic” opponents – 5 beaten – increased significantly compared to the 4 beaten in 2019[17]. One anti-Fascist and participants of the protest organized by the SocFem Alternative activist group are among the victims.

This group also includes the individuals perceived to be “a fifth column” and “traitors to the Motherland”, mainly the protesters assaulted by the pro-Kremlin nationalist SERB (South East Radical Bloсk) group, led by Igor Beketov (aka Gosha Tarasevich)[18].

SERB activists made themselves visible at the Embassy of Belarus in Moscow. Together with the activists of the National Liberation Movement, they engaged in minor provocations, hooliganism, and attacks against those who gathered to protest at the Embassy.

The theme of threats by the ultra-right remained relevant throughout the year. Personal data of the expert who gave opinion to the court at extremism trials and the names of the judges and witnesses were published in Telegram channels.

Other Attacks

In 2020, we are aware of 1 attack on a homeless person (in 2019, we reported 1 murder and 6 beatings). However, the statistics for this group are particularly unreliable. The media reports beatings and deaths of the homeless, but it is impossible to extract any details from these reports.

The topic of hazing with a xenophobic element in the military is off-limits, and we do not have any detailed information about any such incidents. The military itself actively denies such incidents. A video message about ethnic discrimination in the army, posted on Instagram by a Tuvan conscript on 10 January 2021, may be considered as indirect evidence. Private Shoigu Kuular claimed that he and other conscripts from Tuva were humiliated by the unit commanders in Rostov Veliky[19]. Characteristically, many readers complained about xenophobic threats and attacks in the comments to the post.

Crimes against Property

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites, and property in general. They are categorized under several different articles of the Criminal Code, but the enforcement is not always consistent. Such acts are usually referred to as vandalism, and we used to apply this term, too, before rejecting it two years ago, as the term “vandalism”, be it in the Criminal Code or everyday language, clearly does not encompass all possible types of damage to property.

In 2020, the numbers of religious, ethnic, or ideological hate crimes against property were higher than in 2019: 29 incidents in 21 regions in 2020 vs. at least 20 in 17 regions in 2019. Our statistics does not include isolated cases of neo-Nazi graffiti and drawings on buildings and fences but it does include serial graffiti (law enforcement considers graffiti to be either a form of vandalism or a means of public statement).

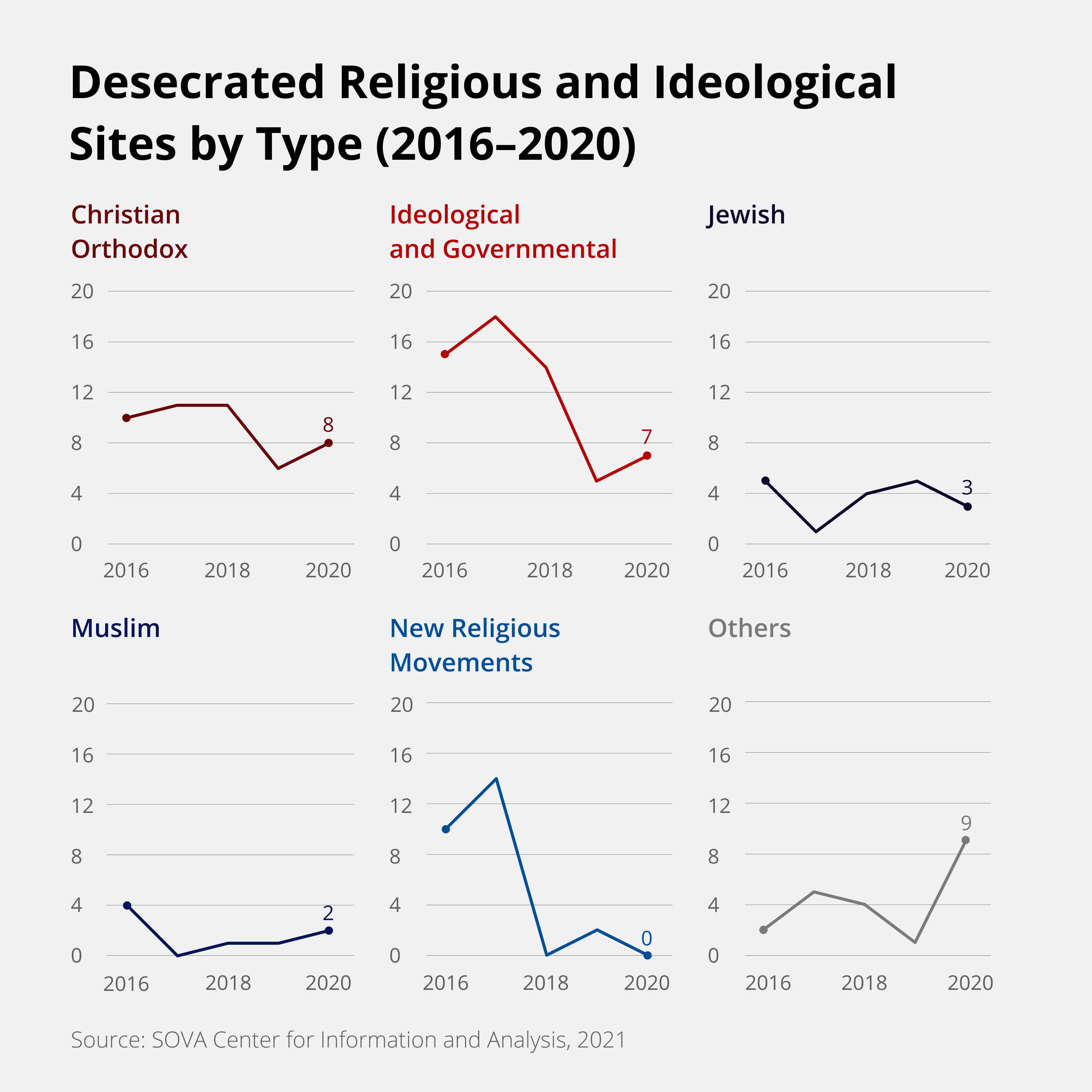

The number of ideological sites and objects damaged in 2020 was somewhat higher – 6 ideological sites and one national, which is slightly more than a year earlier (5 ideological sites in 2019). The sites that sustained damage included monuments to military glory, monuments to Lenin, and a monument to the Gulag victims.

The desecration of images of and monuments to “ethnic enemies” deserve a separate mention: in Chelyabinsk, “Not our hero” was written in black paint on the image of the Dagestani athlete Khabib Nurmagomedov, in Astrakhan, paint was poured and a swastika was drawn on the bust of the ethnographer and Nogai educator Abdul-Hamid Dzhanibekov and the monument to the Tatar poet Gabdulla Tukai was smeared with blue paint and a white swastika was drawn over it.

Traditionally, most of these acts target religious sites and objects. As in 2019, Russian Orthodox churches and crosses were the most frequent target of desecration (8 incidents in 2020 vs. 16 in 2019). Jewish sites come in second with 3 instances (5 in 2019). Pagan sites take the third place with 3 attacks (none in 2019). Muslim and Protestant sites and objects had 2 incidents each (in 2019, 1 attack against a Muslim site, and none against Protestant ones), and a Buddhist site had 1 incident (none in 2019).

On the overall, the number of attacks against religious sites has increased slightly: 19 in 2020 (in 2019, we reported 15 incidents, down from 20 in 2018). The share of the most dangerous acts – arson and explosions – has somewhat decreased compared to the previous year and represents 24%, or 7 out of 29 (in 2019, it was 6 out of 20).

The regional distribution has changed noticeably throughout the year. In 2020, this type of crime was reported in 13 new regions: the Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Voronezh, Kaluga, Murmansk, Nizhny Novgorod, Ryazan, and Chelyabinsk regions, the Altai Republic, Bashkortostan, Komi, Khakassia, and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug; on the contrary, the following 9 regions where such crimes have been reported before went off the list in 2020: Vladimir, Volgograd, Irkutsk, Kaliningrad, Novosibirsk, and Tver regions, Sevastopol, Altai Krai, and Stavropol Krai.

For the second year in a row, the geographical spread of the xenophobic vandalism (21 regions) turned out to be wider than that of the acts of violence (11 regions). Both types of crimes were recorded in five regions (the same number as in 2019 and 2018): in Moscow, St.-Petersburg, and the Arkhangelsk, Voronezh, and Kaluga regions (the last 3 regions are different in 2020 from those in 2019 and 2018).

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

In 2020, the number of those convicted of violent hate crimes was practically the same as a year before. In 2020, in Moscow, St. Petersburg, the Novosibirsk region, and Stavropol Krai saw at least 5 guilty verdicts, in which the hate motive was officially recognized[20]. 8 defendants were found guilty in these trials (9 in 2019).

Racist violence was categorized under the following articles containing hate motive as a categorizing attribute: “Murder” (Paragraph K of Part 2, Article 105 of the Criminal Code), “Hooliganism” (Paragraphs B and C of Part 1, Article 213 of the Criminal Code), and “Battery” (Article 116 of the Criminal Code). This is a standard set of articles used in the last five years. One conviction for violent crimes was based on Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of hatred”) (compared to 3 in 2019). In June 2019 in the city of Nevinnomyssk of Stavropol Krai, a 25-year-old local resident punched an unfamiliar 37-year-old woman in the face, shouting racial slurs and calls for violence “against representatives of her ethnic group.” The next day, the suspect attacked a 30-year-old man in a similar manner. He was convicted under Paragraph A of Part 2, Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“Incitement of hatred committed with the use of violence”). We believe that in this case it would be more appropriate to apply another article with the categorizing attribute, perhaps Article 116, 115, or 112 of the Criminal Code (depending on the severity of the inflicted injuries). However, this application of Article 282 is also possible: the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 28 June 28 2011 No. 11 “On Court Practice on Criminal Cases on Crimes of an Extremist Nature”[21] clarifies that Article 282 of the Criminal Code may be applied to violent crimes if they are aimed at inciting hatred in third parties, for example, in the case of a public and demonstrative ideologically motivated attack.

Penalties for violent acts were distributed as follows:

- 2 persons sentenced to 6 years in prison;

- 1 person sentenced to 4 years in prison;

- 1 person received suspended sentence;

- 4 persons sentenced to fines.

We have doubts about the suspended sentence that a resident of Novosibirsk received for attacking a native of Buryatia on the regional train. The leniency of the sentence is perhaps explained by the fact that the attacker pleaded guilty and repented, and the victim’s injuries were not serious (other passengers on the train stepped in to protect him, stopped the attack, and handed the attacker over to the police). However, we do not believe a suspended sentence for an ideologically motivated attack is an adequate punishment: often this provides aggressive young men with a sense of impunity and fails to prevent them from carrying out similar attacks in the future.

The fines handed down to four far-right activists in St. Petersburg for attacking a man they thought was an anti-Fascist can also be explained by the sincere remorse of the perpetrators and their minor age. On the other hand, “spraying gas in the face,” threatening with knives and “a shot in the face from an aerosol pistol” should have resulted in a more severe sentence than the fines between 10,000 and 40,000 rubles. Especially keeping in mind that one of the suspects in this case was Dmitry Nedugov, a member of the well-known neo-Nazi group NS/WP; in the end, he was not charged in this case.

The others convicted in 2020 were sentenced to terms between 4 and 6 years, which seems to be quite proportionate to their crimes.

We should mention separately the sentences that we believe were given for xenophobic violence, although the motive of hatred was not included in the charges or we are not aware of it. Characteristically, all the attackers received suspended sentences or were sentenced to restriction of freedom.

On August 7, two people received suspended sentences under Part 2 of Article 213 of the Criminal Code for an attack on Nigerian nationals on the subway. In August, Artyom Vlasov received one year suspended sentence under the same article for participating in the attack on an anti-fascist concert at the “Tsokol” club on September 2, 2018. On February 6, 2020, the Basmanny District Court of Moscow sentenced Anton Berezhny to 1 year and 11 months of restriction of freedom for an attack on a gay couple in June 2019. Berezhnoy attacked the young men with a knife, shouting homophobic slurs. One of the victims, Roman Yedalov, died on the spot, the other, Yevgeny Efimov, received a non-life-threatening wound. Berezhny was charged with murder (Part 1 of Article 105 of the Criminal Code) and battery (Article 116 of the Criminal Code), but the jury, while finding him guilty of attacking Yefimov, found him not guilty of murder. We do not understand how this could have happened. All we know is that during the trial, Berezhnoy admitted his guilt in the attack but denied his guilt in the murder and said that Edalov “fell on the knife.”[22]

At the year end, news of the 2003-2007 homicide investigations came out completely unexpected.

In October 2020, the investigators reported that the first suspects had been identified in the case of the brutal double murder of Shamil Odamanov (Udamanov) from the Dagestan region and a native of Central Asia. The video showing the decapitation of Odamanov by the far-right against the background of a swastika flag and the shooting of the second victim at point-blank range appeared on the Internet in the summer of 2007[23]. The video was initially alleged to be a fake, but the father of the deceased Odamanov identified the victim in the video as his son[24]. The video was widely distributed on the Internet; every year the prosecutor's office reported punishments of ordinary social networks users who published this video, while nothing was heard about the murder investigation. Suddenly, in October 2020 – 13 years later! – it was reported that the neo-Nazi Sergei Marshakov, who is serving a sentence for shooting at FSB officers, and the former member of Format-18 Maxim Aristarkhov, who is also serving time in jail, were charged in this case. It is also reported that before his death, Maksim (Tesak) Martsinkevich confessed to this murder and his involvement, together with members of nationalist organizations, in other murders of people of “non-Slavic appearance” carried out between 2002 and 2006[25].

In late December, other members of well-known Nazi gangs were also detained in Moscow, Sochi, and Tyumen: Semyon (Bus) Tokmakov, one of the most famous leaders of the Moscow skinheads of the late 90s, previously the leader of the Nazi skinhead brigade Russian Goal and the youth organization of the far-right People’s National Party (Russian: Narodnaya Natsionalnaya Partiya, NNP), Andrey Kail, the successor of Bus in the NNP, Alexander Lysenkov, also a member of the NNP, Maxim Khotulev, Pavel Khrulev (Myshkin) and Alexey Gudilin. They are accused of involvement in a series of “particularly serious crimes including the murders of Central Asia nationals” committed in the early 2000s. The Investigative Committee reports that the crimes surfaced as part of the investigation of the above-mentioned double murder[26].

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

In 2020, we are aware of just one sentence for crimes against property where hate motive was cited (In 2019, we have no information about such sentences; in 2018, we wrote about 2 sentences against 6 people in 2 regions.)

In Volgograd, a local resident received a 1.5-year suspended sentence under Part 2 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code ("Vandalism motivated by national hatred") and Article 280 ("Public calls for extremism") combined with a 2-year ban on the right to engage in activities related to the administration of websites on the Internet. We find this punishment proportionate to the offense of drawing several swastikas and a target sign and writing an anti-Semitic slur in the summer of 2018 on the monument at the memorial complex "The front line of the defense of Stalingrad in November 1942, the troops of the 62nd and 64th armies." Although compulsory, unpaid community work to be done in free time would have been an even more appropriate sentence.

Exactly such punishment was imposed on another anti-Semitic graffiti artist in the Vologda region. On 10 February 2020, the magistrate’s court for the 42nd judicial district of the Oktyabrsky court district sentenced Vyacheslav Kotenko to 280 hours of compulsory community work for drawing a yellow cross on the monument to Holocaust victims in the village of Aksay, installed in 2018 with the support of the Russian Jewish Congress as part of the project “To Restore Dignity.”[27] In this case, the sentence was given under Part 1 of Article 214 of the Criminal Code, and the motive of hatred was not included in the charge.

[1] In 2020, our work on this issue was supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, International Partnership for Human Rights, and the European Commission.

On 30 December 2016, the Ministry of Justice has forcibly listed SOVA Center as “a non-profit organization performing the functions of a foreign agent.” We disagree with this decision and have filed an appeal against it. The author of this report is a Board member of SOVA Center.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2009 (available on the OSCE website in multiple languages, including Russian: http://www.osce.org/odihr/36426).

Alexander Verkhovsky. Criminal Law on Hate Crime, Incitement to Hatred and Hate Speech in OSCE Participating States (2nd edition, revised and updated). Мoscow, 2015 (available on the SOVA Center’s website: http://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/cl15-text.pdf).

[3] Data for 2020 and 2019 is provided as of 20 January 2021.

[4] In our 2020 report, we reported 5 dead and 45 injured and beaten. See: Natalia Yudina. Criminal Activity of the Ultra-Right. Hate Crimes and Counteraction to Them in Russia in 2019 // SOVA Center. 2020. 4 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2020/02/d42031/).

[5] Remarkably, this year the number of Caucasus natives was higher than that of the natives of Central Asia, whereas typically, it is the opposite.

[6] A resident of Kogalym is threatened by social media users because she is married to a Chechen // SOVA Center. 2020. 7 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2020/02/d42056/).

[7] Xenophobia and Nationalism // Levada-Center. 2020. 23 September. (https://www.levada.ru/2020/09/23/ksenofobiya-i-natsionalizm-2/).

[8] Riots on Manezh Square in Moscow //SOVA center. 2010. 12 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2010/12/d20481/).

[9] Galina Kozhevnikova. Is the a unique moment // SOVA Center. 2010. 8 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2010/12/d20452/).

[10] In Yekaterinburg, the Cossacks conduct raids to find people of Asian appearance with cold symptoms // SOVA Center. 2020. 21 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2020/02/d42118/).

[11] Azerbaijani national detained in St. Petersburg in extremism criminal case for attack on Armenians // Mediazona. 2020. 6 August (https://zona.media/news/2020/08/06/spb).

[12] Human rights activists warn about the risk of the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict escalation in Moscow // Kavkazskiy Uzel. 2020. 30 July (https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/352464).

[13] Attitudes toward LGBT People // Levada-Center. 2019. 23 May (https://www.levada.ru/2019/05/23/otnoshenie-k-lgbt-lyudyam/).

[14] Maxim “Tesak” Martsinkevich in Brief // SOVA Center. 2020. 1 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/news-releases/2020/10/d42991/).

[15] Arkhangelsk: Martsinkevich’s fans hold a raid in his memory // SOVA Center. 2020. 5 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2020/10/d43004/).

[16] The attack in Saratov // SOVA Center. 2021. 11 January (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2021/01/d43477/).

[17] Attacks of this type peaked in 2007 (7 killed, 118 injured); the numbers have since been steadily declining. After 2013, trends have been unstable.

[18] For more details see: Vera Alperovich, Natalia Yudina. Pro-Kremlin and Oppositional – with the Shield and on It: Xenophobia, Radical Nationalism and Efforts to Counteract them in Russia during the First Half of 2015 // SOVA Center. 2015. 31 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2015/08/d32675/ p>

[19] “His last name is not Shoigu”: Details of the scandal with a conscript who revealed discrimination in the army // 76.ru. 2021. 13 January (https://76.ru/text/incidents/2021/01/13/69694056/).

[20] Only the verdicts in which the hate motive was officially recognized and which we consider appropriate are included in this count.

[21] For more on this see: Vera Alperovich, Alexander Verkhovsky, Natalia Yudina. Between Manezhnaya and Bolotnaya: Xenophobia and Radical Nationalism in Russia, and Efforts to Counteract Them in 2011 // SOVA Center. 2012. 5 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2012/04/d24088/).

[22] “He Fell on the Knife”: Person Involved in the Murder of a Gay Male Acquitted // SOVA Center 2020. 26 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/news-releases/2020/02/d42138/).

[23] In Adygea, a student who posted a neo-Nazi video on the Internet is charged under Article 282 of the Criminal Code // SOVA Center. 2007. 19 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/against-cyberhate/2007/10/d11796/).

[24] Relatives of the missing Dagestani native recognize him in a neo-Nazi video posted on the Internet // SOVA Center. 2008. 4 June (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2008/06/d13503/).

[25] Suspects announced in the double neo-Nazi murder committed in the 2000s // SOVA Center. 2020. 21 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2020/10/d43089/).

[26] Suspects arrested in a series of racist murders // SOVA Center. 2020. 25 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/news-releases/2020/12/d43443/).

[27] Sentence imposed for desecration of the monument to Holocaust victims in the Volgograd region // SOVA Center. 2020. 12 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2020/02/d42077/)