Articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses Related

to Public Statements

Data Analysis Methods

Data on Articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses Related to

Public Statements

Incitement to Hatred (Article 20.3.1 CAO)

Insulting the State and Society on the Internet

(Article 20.1 Parts 3–5 CAO)

Discrediting the Use of the Armed Forces and Actions

of Officials Abroad (Article 20.3.3 CAO)

Calls for Violating Russia’s Territorial Integrity or

for Sanctions against Russia (Articles 20.3.2 and 20.3.4 CAO)

Display of Prohibited Symbols (Article 20.3 CAO)

Distribution of Extremist Materials (Article 20.29

CAO)

Conclusion

In recent years, SOVA Center has been monitoring the application of articles of the Russian Code of Administrative Offenses (CAO) that regulate public statements. Some of these articles are based on the provisions of the 2002 law “On Countering Extremist Activities,” while others were added in recent years due to the intensification of protest sentiments and political debate, including in connection with the military actions in Ukraine, and the state's desire to control public discussion. This report summarizes our observations on how these legal norms were applied in 2023 and 2024. The report’s sources include statistical data from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of Russia,[1] information about the work of Russian courts published by the State Automated System “Pravosudie,”[2] news reports posted on our website over the past two years, and the database of court decisions analyzed by SOVA. The database is publicly available on our website. We also express our gratitude to the human rights media project OVD-Info[3] for the opportunity to receive and process updates from Russian court websites.

Articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses Related to Public Statements

Under Russian law, administrative offenses are minor ones that differ from crimes in that they do not cause significant harm to society or pose a serious threat to public safety. This explains the absence of a criminal record and generally less severe sanctions for offenders.

At the same time, the system of counteracting extremism is based on the framework law that, in its definition of extremist activity, combines acts that vary in the degree of threat they pose to the public, from terrorism to demonstrating prohibited symbols. Unsurprisingly, the articles of the CAO based on the law on counteracting extremism gradually became closely linked with the relevant norms of the Criminal Code (CC), as did some other administrative articles on public statements. On the one hand, introducing a prior administrative punishment mechanism[4] blurred the line between administrative and criminal prosecution.[5] On the other hand, penalties under these administrative articles have increased in severity.

This report will discuss the application of the following articles of the CAO: 20.3 (propaganda or public display of prohibited symbols), 20.29 (mass distribution of extremist materials), 20.3.1 (incitement to hatred), 20.3.2 (calls for violation of Russia’s territorial integrity), 20.3.3 (discrediting the actions of the army and officials abroad), 20.3.4 (calls for sanctions against Russia), as well as parts 3–5 of Article 20.1 on disorderly conduct (dissemination on the Internet of information expressing obvious disrespect for society, the state, state symbols, the Constitution or the authorities in an indecent form).[6]

Articles 20.3.1 and 20.3.2 were added to the CAO as part of the "partial decriminalization" of the corresponding Criminal Code provisions (Articles 282 and 2801 CC), introducing a preliminary administrative mechanism aimed at making the legislation more humane. Articles 20.3.3 and 20.3.4 were created in 2022, simultaneously with the introduction of the corresponding criminal articles 2803 and 284 into the CC, thus providing the preliminary administrative punishment mechanism from the outset. In the case of Article 20.3, the legislation has become more severe – in 2022, Article 2824 was introduced into the Criminal Code to address repeated displays of prohibited symbols. Thus, among the administrative norms listed above, only Article 20.29 and Parts 3–5 of Article 20.1 do not trigger criminal prosecution for a repeat offense within one year.

The CAO provides for the following sanctions: administrative fines, administrative arrest, community service, warnings, confiscation of the instrument or object used in the offense, administrative suspension of an organization's activities, and administrative deportation of foreign nationals and stateless persons from Russia, among others. It should be noted that, in some cases, courts order the confiscation of equipment – such as computers, laptops, smartphones, modems, and data storage devices – from individuals punished for public statements made on the Internet, treating these items as instruments of the offense, even when their value significantly exceeds the amount of the administrative fine. Furthermore, individuals punished under Articles 20.3 and 20.29 CAO lose their passive electoral rights for a year. Since 2024, they also cannot serve as electoral commissioners with full voting rights.

Data Analysis Methods

The Judicial Department at the Supreme Court publishes its general statistical data on the application of the articles of the CAO relevant to our study twice a year. We will provide the Judicial Department’s data on the total number of offenders punished in 2023 and 2024 and the types of punishments imposed for each article: first for the articles that specifically address speech, then display of prohibited symbols, followed by distribution of extremist materials, and finally the totals.

We will also use the information about court sentencing decisions in 2023–2024 that we obtained from court websites and entered into our database. The percentage of court decisions that we were able to review in 2024 has increased significantly compared to 2023.

When analyzing the data, including year-to-year comparisons, we use several parameters to group the court decisions that we have examined and entered into our database. We then extrapolate the resulting percentages to the total number of sentencing decisions under each article in 2023 and 2024, as reported by the Judicial Department. Summing up the results across all articles provides a general picture of how administrative law is enforced in our area of interest, according to our selected parameters—for example, allowing us to compare the number of people punished for public statements made online versus offline.

Similarly, we analyze law enforcement during the last two years, sorting the court cases into the following tentative categories, depending on the nature of the public statements that served as the basis for the charges (some cases may belong to several categories at the same time):

- cases based on statements characterized by ethnic xenophobia;

- cases based on statements related to religion;

- cases based on criticism of the authorities and their supporters;

- cases based on statements related to events in Ukraine;

- cases based on propaganda of criminal subculture (AUE);

- other cases, including undetermined.

It is also worth noting that once we have reviewed information about a particular case and entered it into our database, we assign it a rating based on whether we consider the restriction of freedom of expression in that case to be justified. Our ratings include: “Yes” – if we view the act as related to xenophobia and the restriction as generally justified; “No” – if we believe the restriction violated the right to freedom of expression and was therefore inappropriate; “Other” – if the restriction was justified but unrelated to countering xenophobia; “Not sure” – if we cannot clearly assess the case for any reason; and “Don’t know” – in cases where there is a significant lack of data for evaluation. This report presents such assessments for the full set of 2023 and 2024 cases related to the articles of interest.

The overall results of the analysis will be summarized in the report’s conclusion.

Data on Articles of the Code of Administrative Offenses Related to Public Statements

Incitement to Hatred (Article 20.3.1 CAO)

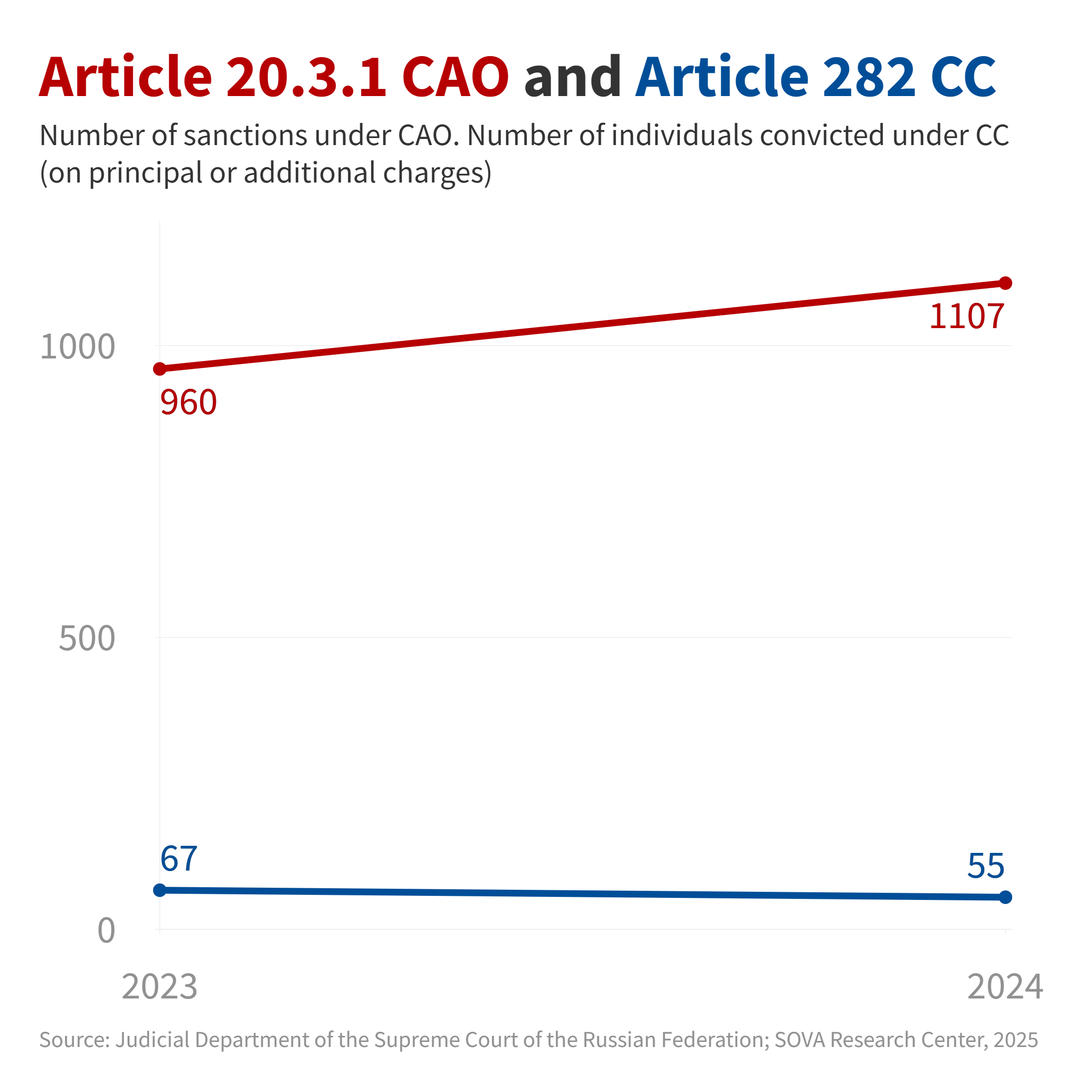

According to our calculations, based on the aggregated data from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court for Article 20.3 and Article 20.3.1 CAO as well as the data from court websites, the total number of individuals punished under Article 20.3.1 (incitement to hatred or enmity, as well as humiliation of human dignity) in 2024 was close to 1,107.[7] In the preceding year, about 960 such sentences were issued, so we see an increase of 15 %.

The graph below compares the number of sanctions imposed under Article 20.3.1 CAO to the number of convictions under Article 282 CC for incitement to hatred. The latter applies in cases where such offenses are committed repeatedly or under aggravating circumstances.

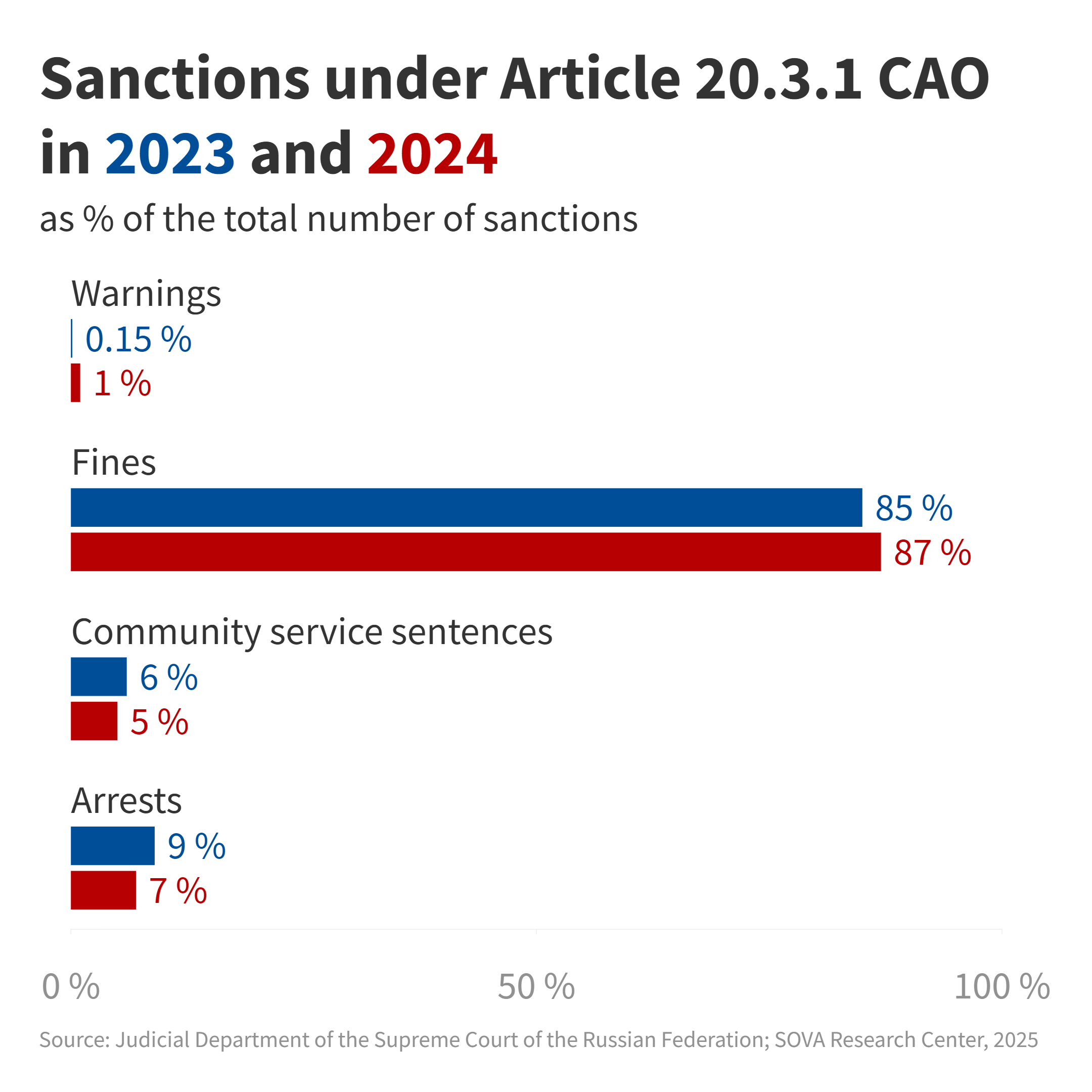

Based on our own data in combination with the data provided by the Judicial Department, we assume that in 2024 courts imposed fines on offenders under Article 20.3.1 CAO in 87 % of cases, administrative arrest in 7 % of the cases, community service in 5 %, and only issued warnings in 1 %. In 2023, according to our calculations, the distribution of punishments was 85 %, 9 %, and 6 % respectively, with only one warning.

SOVA Center has reviewed 650 court sentencing decisions under this article, that is, 59 % of such decisions made in 2024, and 390 decisions (i.e. 41 % of all sentences issued during the year) in 2023.

In 2024, 94 % of known sentences were issued for online statements (social network posts and comments, videos, images, etc.) and only 6 % for offline statements (mostly for xenophobic utterances and statements made during ordinary conflicts). In 2023, the ratio remained approximately the same: 93 % and 7 %.

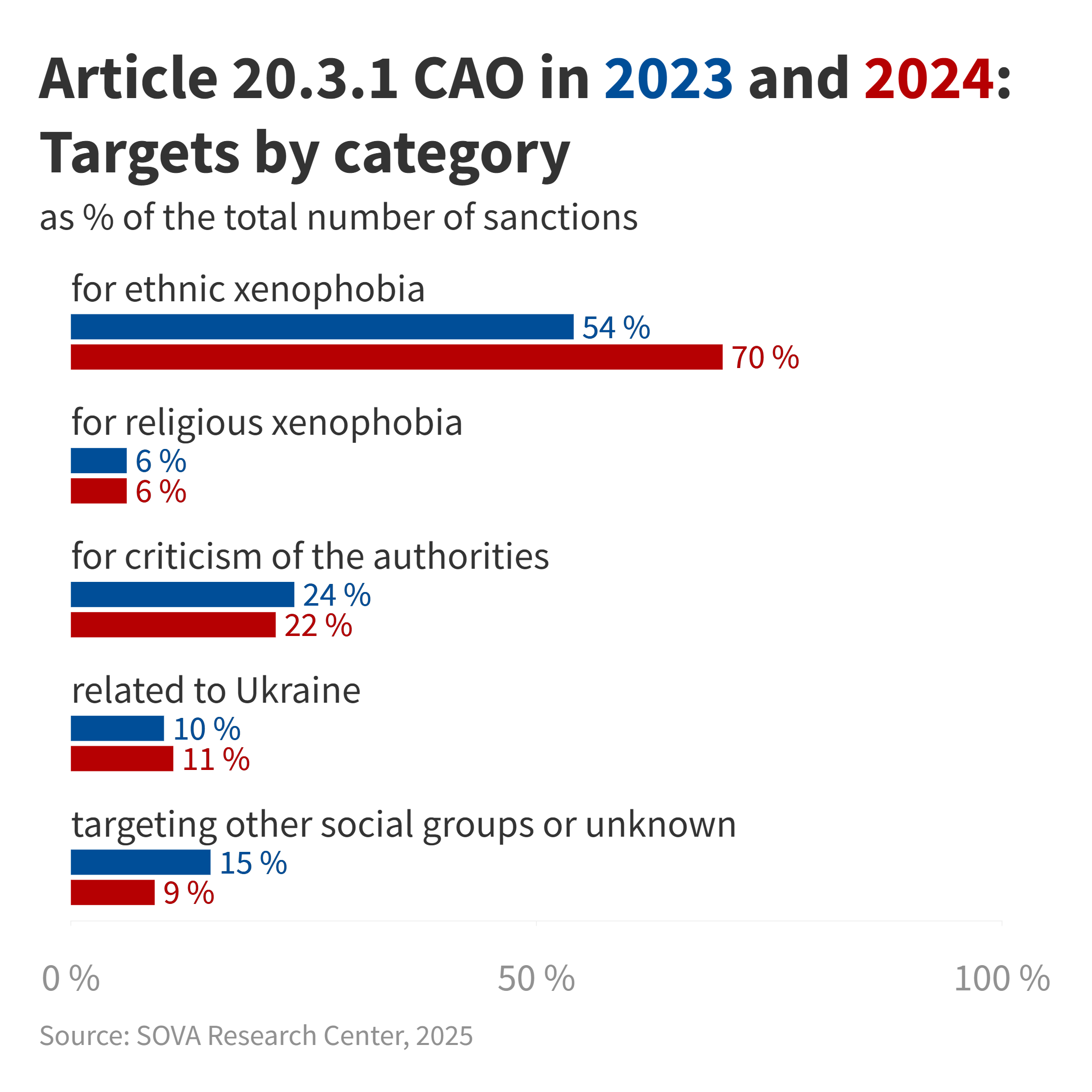

Now, let us examine the distribution of decisions under Article 20.3.1 CAO that were entered into our database across the categories outlined above, based on the target of hostile statements or criticism. In 2024, in approximately 450 out of 650 cases, i.e., in 70 % of cases, the statements that incurred punishment expressed ethnic xenophobia. A year earlier, we counted 210 such cases out of 390, i.e., 54 %. With respect to targets of hostility, the cases within this category were distributed as follows (please note that a single case could involve statements against representatives of different communities).

| Target of Hatred / Year |

2023 |

2024 |

|

non-Slavs and migrants in general |

6 |

41 |

| natives of Central Asia |

54 |

131 |

| natives of the Caucasus |

52 |

117 |

|

Jews |

39 |

69 |

|

Russians and citizens of Russia[8] |

43 |

58 |

|

other[9] and unnamed communities |

91 |

95 |

In 2024, followers of specific religions were the targets of hostility in 42 cases (6 %). In 2023, 24 such cases were entered into the database – that is, the same 6 %. In most cases, these cases also included statements expressing ethnic xenophobia, so this category mostly overlaps with the previous one.

|

Target of Hatred / Year |

2023 |

2024 |

|

Muslims |

3 |

12 |

|

Christians |

5 |

12 |

| Jews |

2 |

5 |

|

“infidels,” i.e., non-Muslims |

17 |

5 |

| other believers |

5 |

8 |

In four cases, in both 2023 and 2024, we found the charges to be inappropriate, as they were based not on incitement to hatred against believers, but on criticism of Christianity from an atheistic perspective, criticism of the Russian Orthodox Church as an organization, and its policies regarding the “special military operation,” etc.

In 2024, we categorized 140 cases out of 650, i.e., 22 % of all cases, as sanctions for criticizing the authorities and their supporters (vs. 93 out of 390, i.e., approximately 24 % in 2023). The cases were distributed as follows.

|

Target of Hatred /Year |

2023 |

2024 |

| law enforcement staff (in general, as well as police, Russian National Guard, FSB, etc.) |

46 |

74 |

|

the authorities (in general, officials, representatives of the United Russia party, etc.) |

23 |

39 |

| the president (personally) |

15 |

4 |

|

Russian military |

10 |

21 |

|

government supporters, “Russians” and “citizens of Russia” as political opponents |

17 |

26 |

Further clarification is warranted here.

First, the table above includes some cases related to negative assessments of Russians or Russian citizens coming from their compatriots – people who consider themselves to be members of the same community. In our opinion, such assessments should often be interpreted not as incitement to hatred or the humiliation of dignity based on ethnicity, but rather as, albeit harsh, criticism of the shortcomings of Russian society or the presumed political stance of the majority of fellow citizens in support of the government's course. These statements express antipathy towards one’s opponents within the framework of a political discussion.

Next, we believe that the presence of the vague category of “belonging to a social group” in the laws concerning incitement to hatred allows for selective enforcement, protecting groups favored by the authorities rather than genuinely vulnerable populations, such as the homeless or people with disabilities. In fact, this is exactly what happens: charges can involve incitement of hatred towards social groups such as law enforcement staff, government officials, the military, supporters of the authorities and the special military operation, patriots, and citizens of Russia.

We consider charges related to statements about members of these groups to be legitimate only when they involve clear calls for violence. We have recorded only 26 such cases in this category in 2024 (19 %) and the same number (26 or 28 %) in 2023. If a statement only criticizes representatives of such groups, albeit harshly, we classify the corresponding case as inappropriate, since the targets are people in power or people clearly not at risk of discrimination. We counted 91 such cases in 2024 (65 % of this year’s cases based on statements critical of the authorities) and 40 (43 %) in 2023.

It should be noted that some cases under Article 20.3.1 CAO are related to statements about the events in Ukraine. These cases involve charges of incitement to hatred against the military or supporters of the authorities, and occasionally against Russians and citizens of Russia. In 2024, we counted about 70 such cases, i.e., 11 % of the total number of known court decisions under this article. In 2023, there were 38 such cases, i.e., 10 %. This category clearly occupies the intersection of the two categories mentioned earlier: “ethnic xenophobia” and “criticism of the authorities.”

In 2024, we counted 24 cases of statements directed against representatives of other social groups, vs. 51 in 2023. They involved such targets of hostility as women, children, LGBT+ people, youth groups, homeless people, and representatives of a wide variety of other groups (native speakers of the Karelian language, doctors, motorcyclists, etc.).

The information we have on 54 other cases in 2024 and 48 in 2023, including the texts of the court decisions, does not allow us to form even a vague idea of the incriminating statements or identify the targets of hatred. Unfortunately, when publishing their decisions, courts often remove any substantive information about the underlying incidents, leaving only references to legal provisions.

In total, 60 cases in our database for both years involved statements against representatives of “other social groups” or simply groups not named in the texts of decisions, which could not be classified as “ethnic xenophobia,” “political criticism,” or “religion.” This group represents 9 % of the total number of sentences under this article in 2024 and 15 % in 2023.

So, presumably, decisions on imposing punishments under Article 20.3.1 CAO are distributed between categories as follows (a case may fall into more than one category).

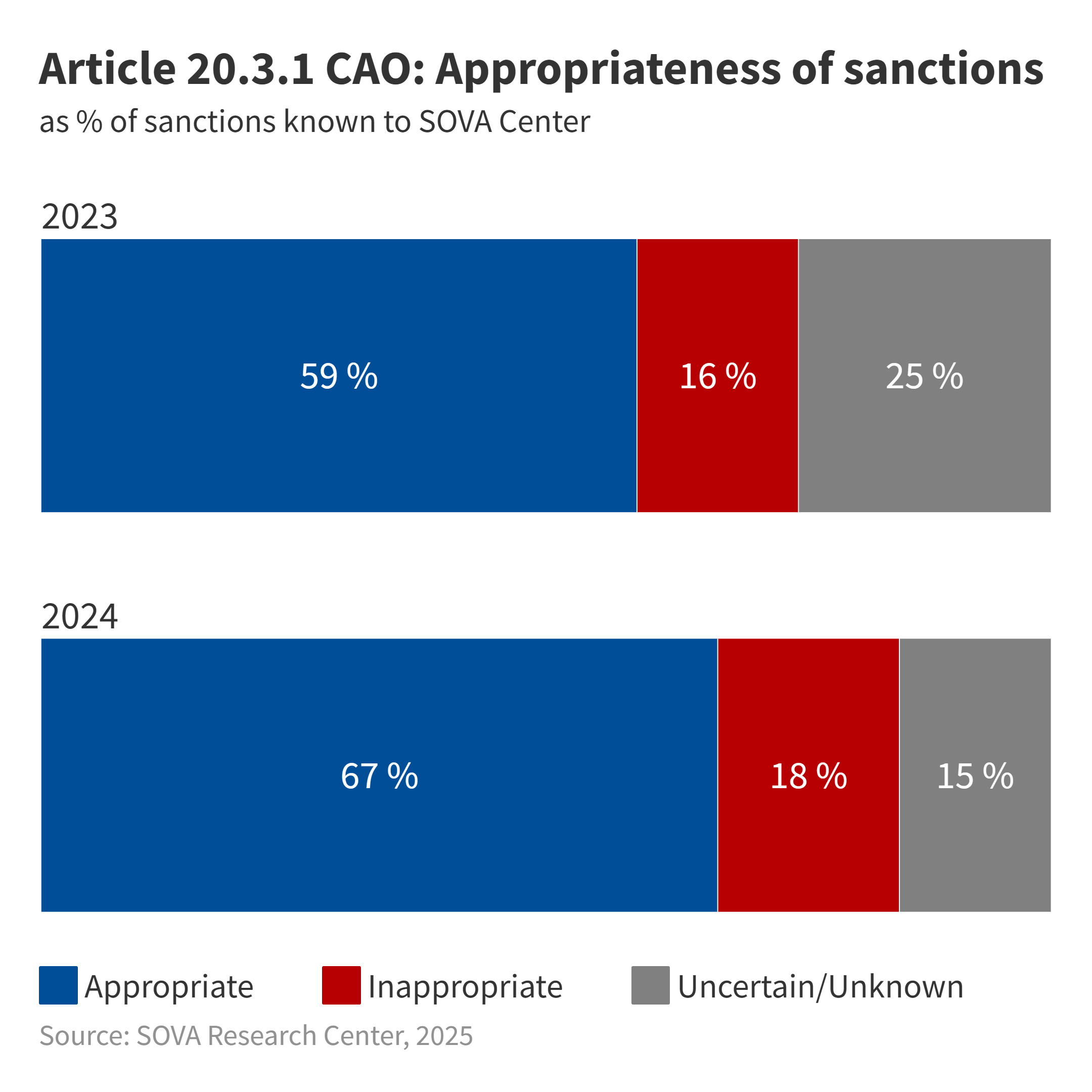

Next, we examine the appropriateness of sanctions under Article 20.3.1 CAO.

Although our access to information increased in 2024 (we examined 650 decisions, compared to 390 the year before), the picture has not changed significantly. In both 2023 and 2024, we classified approximately two-thirds of sentencing decisions under the administrative article on incitement to hatred as appropriate, and no more than one-fifth of such sentences as inappropriate.

Insulting the State and Society on the Internet (Article 20.1 Parts 3–5 CAO)

Unfortunately, the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court does not publish separate data on parts of Article 20.1 CAO that cover dissemination of information expressing disrespect for the state and society in an indecent form on the Internet – only the gigantic totals for the entire Article 20.1 CAO on disorderly conduct.

Based on our analysis of court data, at least 182 individuals faced sanctions in 2024, primarily under Part 3. Only two individuals were found guilty under Part 4 for repeatedly committing the same offense within a year after sentencing. In 2023, similar to 2022, approximately 150 people were charged under Parts 3–5 of Article 20.1 CAO, while the corresponding number in 2020 and 2021 was about 90. Thus, we can say that the frequency of application of the norm on insulting the authorities on the Internet is increasing, although the article remains relatively “unpopular.”

Our database for 2024 includes 40 people punished under this article: 39 faced fines (ranging from 15 to 100 thousand rubles), and one person was placed under arrest. In 2023, we recorded around 27 individuals facing penalties, all of whom received fines.

Almost all of the cases known to us involved disrespect for the president, and several others involved disrespect for the authorities, the military, state symbols, and society as a whole (several individuals were punished merely for their use of obscene language online).

We believe that crude criticism of the authorities or the use of obscene language on the Internet poses no public danger and should not be restricted by the state. Such restrictions constitute unjustified interference with freedom of expression. Therefore, we generally consider the use of Article 20.1 Parts 3–5 CAO inappropriate.

Discrediting the Use of the Armed Forces and Actions of Officials Abroad (Article 20.3.3 CAO)

According to data published by the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, the number of people punished under Article 20.3.3 CAO for discrediting the use of Russian armed forces or actions of state agencies abroad decreased steadily in 2023 and 2024. While in 2022, when this article was introduced into the CAO, sanctions were imposed 4,440 times, there were only 2,361 such instances in 2023 (a 47 % drop), and 1,805 in 2024 (a 24 % decrease from 2023). According to court websites, all the sentences were based on Part 1 of the article.[10]

The graph below compares the number of sanctions issued under Article 20.3.3 CAO with the number of sentences under criminal Article 2803 CC for discrediting the actions of the army and government agencies, committed repeatedly or with aggravating circumstances.

Under the CAO article, the penalty takes the form of a fine. Most often, courts impose fines of 30 thousand rubles. 1,803 individuals punished in 2024 faced fines, one was placed under arrest[11], and one received a warning.

The analysis of about 44 % of court decisions under this article conducted by OVD-Info indicates that in 2024, various anti-war statements and distribution of corresponding materials online formed the most common grounds for sanctions (88 %), much less frequent were the anti-war pickets, displaying posters, distributing leaflets, written messages, including on ballots during elections, and so on (12 %). No such data is available for the preceding year; however, there are reasons to believe that it had the same or a similar ratio of sanctions for online vs. offline statements.

SOVA Center views sanctions under Article 20.3.3 CAO as an unjustified restriction of freedom of expression and classifies all cases under this article as inappropriate.

Calls for Violating Russia’s Territorial Integrity or for Sanctions against Russia (Articles 20.3.2 and 20.3.4 CAO)

According to the Supreme Court's Judicial Department, 38 decisions were made in 2023 and 40 in 2024 to impose sanctions under Article 20.3.2 CAO, which covers calls for violating the territorial integrity of Russia, or under Article 20.3.4, which punishes calls for sanctions against Russia, its organizations, and citizens.

In 2023, 37 individuals were fined, and one was given a warning. In 2024, fines were imposed in 39 cases, and one warning was issued.

In 2023, we were aware of only five court decisions under Article 20.3.2. In 2024, we were able to gather information on 17 decisions. If the statements did not call for violent separatist actions, we deemed the sanctions inappropriate. We recorded three such decisions in 2023 and 13 in 2024. The charges were based on statements regarding the status of Ingushetia, Crimea, Rostov Oblast, Smolensk, Tatarstan, Tuva, and the Urals, as well as the notion of granting independence to all Russian republics and, conversely, the revival of the USSR.

Under Article 20.3.4 CAO, which covers calls for sanctions against Russia, its organizations, and citizens, we know of only one decision made in 2024 (none in 2023): a court in Kazan fined the former leader of the banned All-Tatar Public Center (Vsetatarsky Obschestvennyi Tsentr, VTOTs) for his address, posted on YouTube, that called for demanding that the G7 countries exclude Russia from the UN, impose tough sanctions against Iran and China and other countries which carry out “parallel imports,” and completely stop the export of Russian oil and gas. We believe that the state should not restrict such expressions of opinion.

Display of Prohibited Symbols (Article 20.3 CAO)

According to our calculations, sanctions under Article 20.3 CAO for the use of prohibited symbols were imposed 4,203 times in 2023 and 4,717 times in 2024, thus increasing by 12 %.

The graph below compares the number of sentences under Article 20.3 CAO with the corresponding number under Article 2824 CC (repeated display of prohibited symbols).

According to the data from court websites, only 0.7 % of sanctions in 2023 and 0.8 % in 2024 were imposed under Article 20.3 Part 2 CAO for producing and/or selling prohibited symbols, while the overwhelming majority were imposed under Article 20.3 Part 1 CAO for their public display.

The analysis of our data and that from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court indicates that in 2023, fines were imposed in approximately 91 % of cases, while administrative arrests occurred in 9 %. In 2024, fines were imposed in 87 % of cases, and arrests increased to 13 %. Courts issued warnings only once each year.

SOVA’s data, combined with the data from court websites, suggests that in 2024, approximately 75 % of cases were related to the display of prohibited symbols online, primarily on social networks. The incidents included individual symbols as well as images, photos, or videos containing such symbols. In 25 % of cases, people displayed prohibited symbols offline, as tattoos, clothing items, stickers, or graffiti, shouted corresponding slogans, or even sang or listened to songs on high volume. In 2023, 64 % of cases involved the display of symbols online, while offline symbols accounted for 36 %.

Let us review the types of symbols that most often serve as the basis for sanctions, keeping in mind that a single case may involve multiple types of symbols. Next, we will categorize different cases following the principles discussed earlier in the report.

The court website data provided by the OVD-Info parser indicates that, as in the preceding year, 30 % of sentencing decisions under Article 20.3 CAO issued in 2024 involved an eight-pointed star (“a compass rose”) as the symbol of involvement in the criminal underworld. Law enforcement agencies and courts consider it a symbol of the Prisoners’ Criminal Unity (Arestantskoe Ugolovnoe Yedinstvo, AUE), that is, a criminal subculture banned by the Supreme Court in 2020 as an extremist “international public movement.” The cases are usually based on demonstrating tattoos or publishing images of the eight-pointed star on the Internet. Incarcerated individuals often face sanctions, since jails and prisons provide no means of removing an illegal tattoo, and the lack of privacy makes hiding it from prying eyes almost impossible. Prison artists are punished for drawings that feature an eight-pointed star.

We believe that the ideology of AUE is oriented towards illegal activity and thus is, by its nature, incompatible with honoring the constitutional rights of citizens. Therefore, it can be banned and criminalized. However, in our opinion, this ideology is not political, so anti-extremist legal norms should not be applied against it. We neither monitor cases under Article 20.3 CAO for displaying AUE symbols nor enter them into our database; we doubt the appropriateness of such charges.

If we subtract 30 % of decisions (1383) related to AUE symbols from the approximate total number (4717) of court decisions under Article 20.3 CAO, we get 3334 decisions. Of these, we analyzed about 1100 cases, which represent 33% of the total, and have entered them into our database.

For 2023, we similarly recorded 2920 sentencing decisions (after subtracting those related to AUE symbols) and entered about 820, or 28 %, into our database.

In 2024, approximately 673 out of 1,100 cases in our database (or 61 %) involved charges based on the display of Nazi symbols. In 2023, we recorded 621 such cases out of 820, or 76 %.

Of the cases known to us:

- In 645 instances in 2024 (vs 574 in 2023), the display of Nazi symbols, mainly swastikas, was aimed at promoting Nazism, or we were unable to establish the context. Accordingly, we classify the sanctions for such displays as appropriate or uncertain (if the context is unclear).

- In 17 instances in 2024 (vs. 39 in 2023), Nazi symbols were used as a means of visual criticism of political opponents – to brand them as supporters of “fascism,” an inhuman ideology. Most often, the opponents were the Russian authorities and their supporters (for example, a swastika can be superimposed on images of the president or Russian state symbols, or symbols of the special military operation in Ukraine. We regard sanctions against such displays as inappropriate.

- In three instances in 2024 and nine in 2023, we were confident that the punishment was inappropriately imposed for posting historical photos that included Nazi symbols.

- Approximately ten cases in 2024 and five in 2023 involved the display of Nazi symbols in a humorous context, the use of the Eastern version of the swastika, and online advertisements for the sale of Third Reich-era antiques. We classified such cases as inappropriate or questionable.

Looking at percentages of the total number of sentences under Article 20.3 CAO (i.e., including the decisions on AUE), we can conclude that, as before, Nazi symbols were the most frequent basis for sanctions under this article. They account for 43 % of cases in 2024, although the percentage is smaller than the year before (52 %).

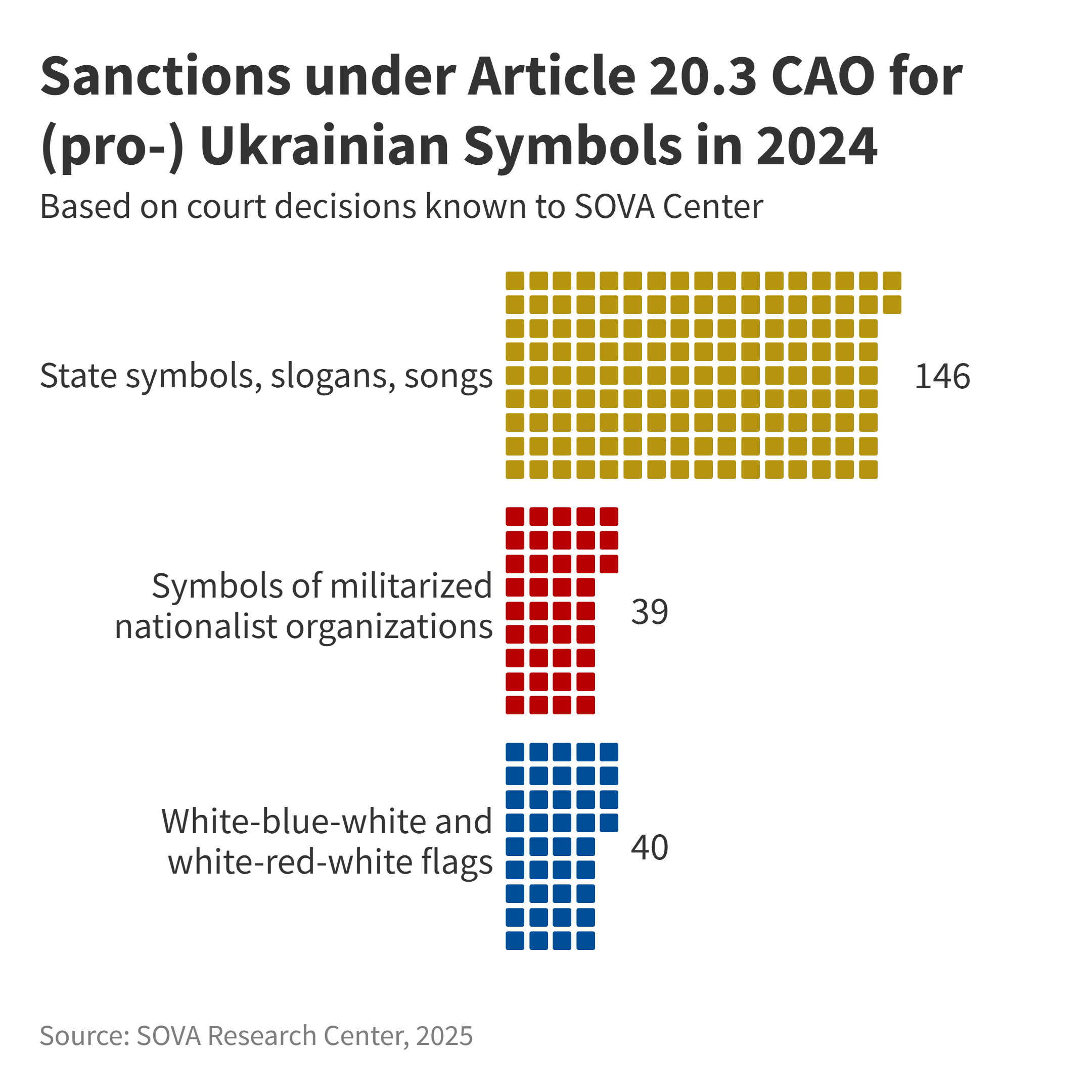

The cases related to the display of Ukrainian paraphernalia, including state symbols, as well as symbols of Ukrainian nationalist organizations and paramilitary Ukrainian and pro-Ukrainian associations, constitute the third most numerous group, after the Nazi symbols and the AUE symbols. We recorded 225 such cases in our database, or about 20 % (vs. 91 or 11 % in 2023). This allows us to assume that 14 % of the total number of sanctions under Article 20.3 CAO were related to Ukrainian symbols (7 % in 2023).

Of the cases known to us:

- In 2024, sanctions in 146 cases (vs. 42 cases in 2023) were imposed for displaying various Ukrainian attributes: the state emblem with the trident or only the trident, the flag, the slogan “Glory to Ukraine,” as well as the folk song “Chervona Kalyna.” Law enforcement agencies and courts interpret them as symbols of Ukrainian nationalist organizations that are banned in Russia as extremist, although, in fact, these attributes are widely used in Ukraine. We consider such cases inappropriate (in the absence of a clearly xenophobic context).

- In 2024, 39 cases (vs. 25 in 2023) were related to the display of symbols of Ukrainian paramilitary nationalist organizations, most often, the Azov Regiment and the Right Sector, as well as units in which people from Russia participate in combat on the side of Ukraine — the Russian Volunteer Corps and the Freedom of Russia Legion. All of these entities are recognized as terrorist organizations in Russia. We often do not know the context in which such symbols were displayed; however, in cases where the intent to promote violence was clear, we considered the charges appropriate.

- In 2024, we classified as inappropriate 40 cases (vs. 26 in 2023) of sanctions for public display of the white-blue-white flag, which law enforcement officers and then courts interpreted as the symbol of the Freedom of Russia Legion. Some of these cases were based on public displays of the white-blue-white flag as an opposition and anti-war symbol. Another similar case in 2024 concerned the display of the white-red-white flag of the Belarusian opposition, which was interpreted as a symbol of the Kastus Kalinouski Regiment fighting for Ukraine. Moreover, as in the previous year, not all citizens punished for displaying the white-blue-white flag had done so intentionally – for example, several motorists faced sanctions due to a faded red stripe on the Russian flag sticker on their license plates.

In 2024, most cases involving symbols of Russian political associations recognized as extremist fell into one of the following two groups.

- 52 people punished in different regions of Russia were found guilty of demonstrating symbols of Alexei Navalny's structures, which were banned – in our opinion, inappropriately. Portraits of the politician or his first and last name, which citizens actively displayed in response to Navalny's sudden death in prison, were often interpreted as symbols of these structures. In 2023, we only recorded 16 decisions of this kind in our database.

- Our database contains six cases related to “I/WE Sergey Furgal” stickers on cars and similar captions on photographs posted on social networks. This slogan is viewed as an attribute of the movement supporting the convicted former governor of Khabarovsk. The movement was recognized as extremist, despite not promoting any radical ideology. The websites of Russian courts show 16 such decisions. All of them were issued in Khabarovsk Krai, except one, which was issued in Zabaikalsky Krai. There were no similar cases in 2023, since the movement of Furgal's supporters was banned in 2024.

Since late January 2024, even before the inclusion of the “international LGBT public movement” on the list of extremist organizations on March 1, citizens have faced charges for displaying LGBT symbols, including the rainbow flag. We consider such charges inappropriate, since we view the ban on the “LGBT movement” as an unfounded and discriminatory measure. In 2024, we recorded 55 cases based on the display of the rainbow flag and entered them into our database; a search of court websites yields 58 similar decisions.

Only a small number of sentences in our database involved displaying symbols of banned Islamic organizations. We counted 43 such cases (4 %) in 2024 and 41 (5 %) in 2023. Mostly, they involved ISIS symbols, and in a few isolated instances, symbols of the Islamic religious party Hizb ut-Tahrir. Of the total number of decisions under Article 20.3 CAO, such cases accounted for under 3 % in both years.

Sanctions for displaying neopagan symbols pose a distinct issue. Our database contains 23 cases for 2024 and 24 cases for 2023 based on charges for displaying neopagan solar symbols: the Kolovrat and the Svarog Square. A search of court websites suggests that about fifty people faced punishment for these symbols in both 2023 and 2024. Law enforcement agencies and courts interpret the Kolovrat as a variant of the Nazi swastika, similar to it to the point of confusion, and the Svarog Square as a symbol of the “Northern Brotherhood,” a now little-known neo-Nazi organization recognized as extremist in 2012. Indeed, both symbols can be used as a visual means of nationalist propaganda. However, ordinary citizens are often unaware of the Northern Brotherhood and, unable to distinguish between Slavic and pseudo-Slavic symbols, commonly perceive the Kolovrat and the Svarog Square simply as traditional Slavic symbols. As a result, they may unwittingly display these symbols on social media or, for example, as pendants and keychains in their cars (widely available items). In practice, law enforcement makes no distinction between nationalist propagandists and uninformed admirers of Slavic aesthetics; both groups are subject to punishment.

A similar situation, albeit on a regional scale, has emerged in Dagestan, where, according to district court websites, at least 31 people faced sanctions in 2024 for pit bull stickers (the logo of Pitbull Syndicate LTD, a racing game company) on their cars. Our database contains about two dozen such decisions. Local law enforcement officials view the stickers as symbols of the neo-Nazi group Pit Bull,[12] banned in 2010. Our database includes 19 such decisions for 2024 and seven for 2023.

We assess sanctions for displaying neo-pagan symbols based on context. As to the charges related to pit bull stickers, they are, in our view, entirely unjustified.

Finally, we know of nine sentences in 2024 for displaying Facebook and Instagram logos on websites or in advertisements. Offenders never intended to participate in activities (recognized as extremist) of the Meta corporation aimed at distributing the two products; they merely disseminated information about their own activities. Eight cases took place in Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug-Yugra, where the heads of five daycare centers, an employee of the local administration, a hotel manager, and an art studio director were punished. The owner of a beauty salon faced charges in the ninth case, in the Oryol Region. In 2023, we recorded three similar cases with sanctions against two entrepreneurs and one human rights activist.

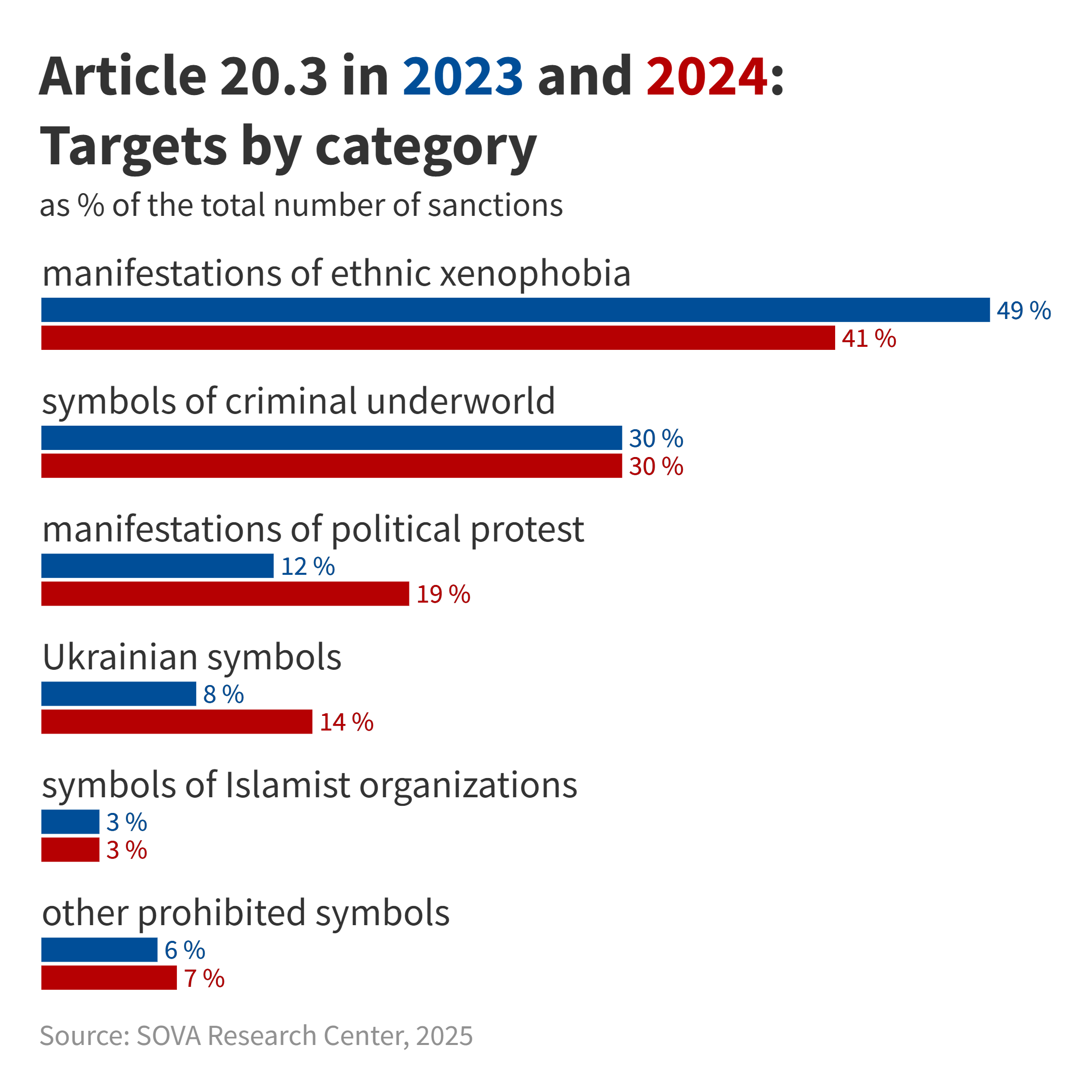

We can now categorize the instances of prohibited symbol displays that led to administrative charges and calculate the percentage each category represents within the total set of court decisions on punishments under Article 20.3. Once again, please note that the categories may overlap. For example, both Nazi symbols and AUE symbols often appear together in the same case. We also included all cases of displaying Ukrainian symbols in the “oppositional protest” category. Thus, 4,717 court decisions issued in 2024 and 4,203 decisions handed down in 2023 in cases related to the display of prohibited symbols, distributed as follows:

- manifestations of ethnic xenophobia (display of Nazi or neo-pagan symbols, except where not clearly intended as far-right propaganda) – 41 % (vs. 49 % in 2023);

- display of symbols of the criminal underworld – 30 % (both years);

- manifestations of political protest (displaying symbols of banned political associations, using Nazi symbols to criticize opponents), including the demonstration of Ukrainian symbols – 19 % (vs. 12 % in 2023);

- display of Ukrainian symbols (national symbols and symbols of paramilitary organizations fighting on the side of Ukraine) – 14 % (8 % in 2023);

- display of symbols of banned Islamic organizations – 3 % (both years);

- display of other prohibited symbols (specifically: LGBT symbols, pagan symbols in a neutral context, pit bull stickers, logos of prohibited social networks, etc., as well as symbols not specified in court decisions) – 7 % (vs. 6 % in 2023).

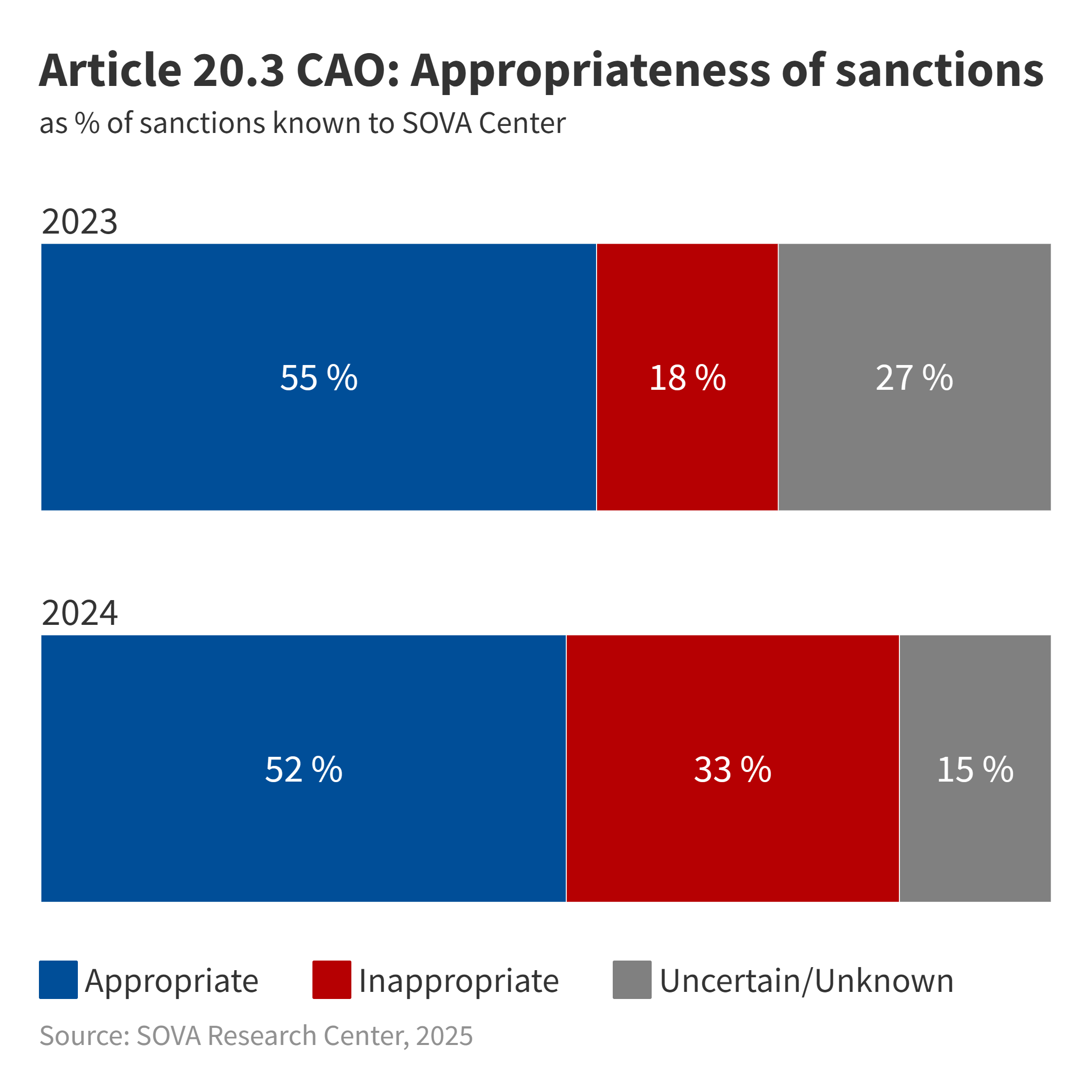

Our overall assessment of the appropriateness of court decisions in our database, expressed as percentages, is as follows:

Clearly, compared to 2023, the percentage of sentencing decisions lacking specific information about the incriminating symbols and their context has decreased, whereas the percentage of inappropriate decisions has nearly doubled.

If we extrapolate these percentages to the total number of decisions under Article 20.3—including cases involving AUE symbols, which we do not assess—the situation is as follows.

|

Year and number of court decisions |

Appropriateness, percentage of court decisions |

||

|

Yes |

No |

Other |

|

|

2023 (4203) |

38 |

13 |

49 |

|

2024 (4717) |

36 |

23 |

41 |

Distribution of Extremist Materials (Article 20.29 CAO)

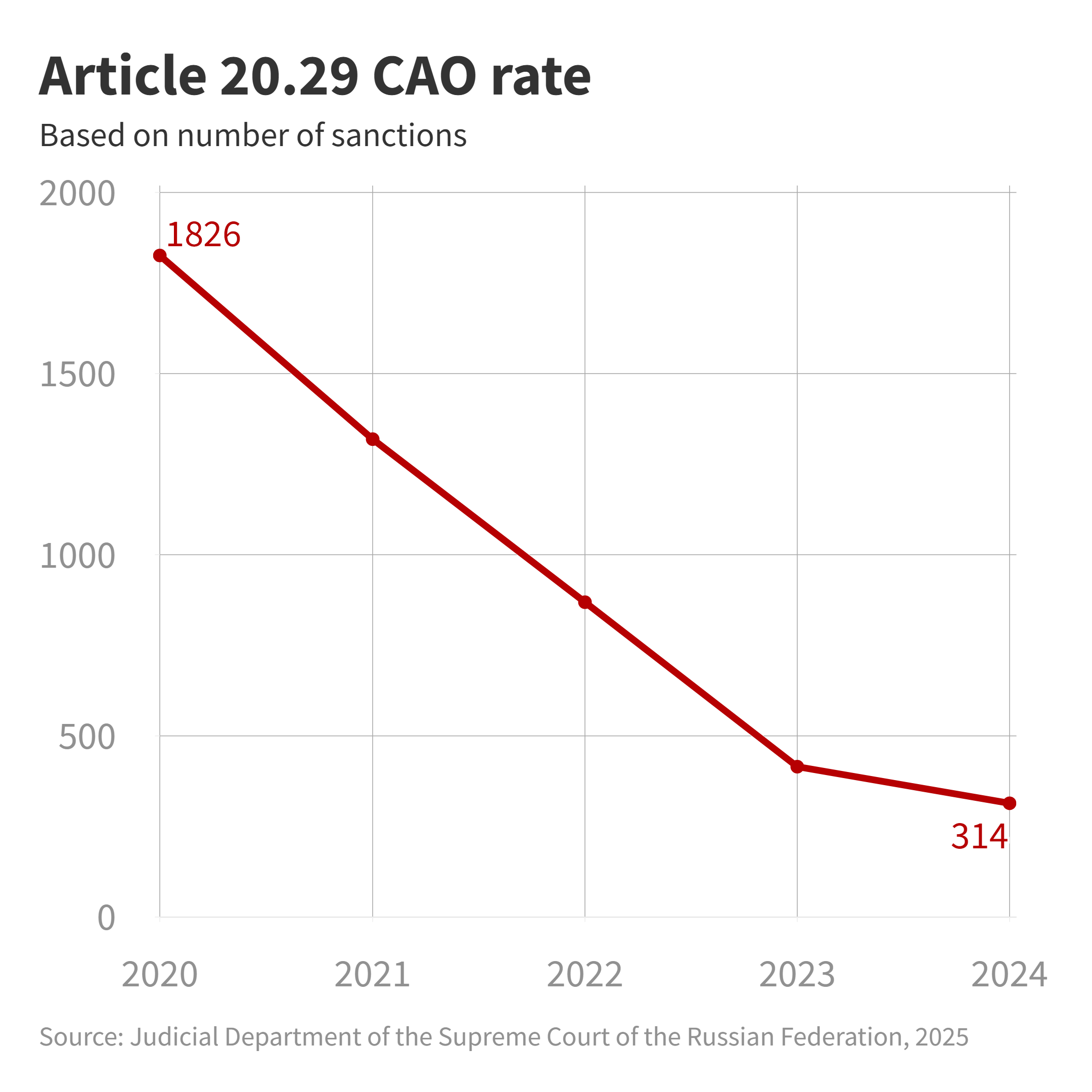

In 2023 and 2024, the number of sanctions under Article 20.29 CAO for mass distribution of extremist materials continued to decline, although the decline has become more gradual.

In 2023, courts imposed fines in 394 cases and administrative arrests in 20 cases. Additionally, one case resulted in a decision to suspend activities. In 2024, 297 people were fined, 16 were placed under arrest, and one received only a warning.

In 2024, we entered 185 out of 314 court decisions into our database, which represents 59 % of all sentencing decisions under Article 20.29 CAO. In 2023, the corresponding figures were 180 out of 415, equating to 43 %.

Of the 2024 decisions in our database, 85 % pertained to the distribution of materials online (usually on social networks), and 15 % to the distribution that took place offline, such as one or more copies of banned books in a public place, for example, on the premises of a religious organization or an educational institution. Bookstores faced administrative responsibility in rare cases, and occasionally individuals who, according to law enforcement agencies, kept banned literature at home “for the purpose of mass distribution.” In the preceding year, 93 % of known penalties were imposed for online offenses and only 7 % for offline ones.

Depending on the type of materials that served as the basis for sanctions, 185 known court decisions of 2024 and 180 of 2023 were distributed among the categories outlined above, as follows.

Dissemination of materials characterized by ethnicity-based xenophobia accounted for 87 (47 %) of the cases in 2024 and 79 (44 %) in 2023.

|

Materials / Year |

2023 |

2024 |

|

videos with scenes of racist violence and other neo-Nazi materials, except music and books |

8 |

48 |

|

songs of ultra-right music groups |

40 |

24 |

|

materials of the German Nazism ideologists and neo-Nazis |

4 |

3 |

|

materials of Russian nationalists |

27 |

12 |

Dissemination of materials related to religion formed the basis of 44 cases (24 %) in 2024, and 24 cases (13 %) in 2023.

|

Materials / Year |

2023 |

2024 |

|

materials of militant Islamists (propaganda videos, ISIS songs, songs of Chechen bard Timur Mutsuraev) |

15 |

22 |

| peaceful Islamic materials |

7 |

20 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses Materials |

2 |

2 |

Cases related to the distribution of various materials that can be classified as political polemics accounted for only 6 % in 2024. In 2023, the percentage of such cases was significantly higher (17 %), due to a greater number of charges for the distribution of a video by Alexei Navalny’s supporters about the election promises of United Russia, which was banned in 2013. Apparently, the number of users whose social media pages hold this old video has been gradually shrinking.

|

Materials / Year |

2023 |

2024 |

|

“Let’s Remind Crooks and Thieves about their Manifesto-2002” video by Navalny’s supporters |

21 |

3 |

| various materials related to events in Ukraine and the banned symbol of the Azov Battalion |

8 |

4 |

|

other political materials |

3 |

5 |

We know of about seven sentencing decisions for prohibited songs related to AUE in 2024 and four such decisions in 2023. They account for 4 % and 2 % of the total number of decisions, respectively.

In 2024, we entered into our database 35 cases (19 %) related to the dissemination of materials that do not fall into the categories provided above or where court decisions failed to specify the materials. There were 44 cases (24 %) in 2023.

Thus, in percentage terms, the materials that formed the basis for charges under Article 20.29 CAO are distributed across the categories as follows.

|

Category of materials |

Materials, % |

|

| 2023 |

2024 |

|

|

ethnic xenophobia |

44 |

47 |

|

religious |

13 |

24 |

|

political |

17 |

6 |

|

related to Ukraine |

4 |

2 |

|

AUE materials |

2 |

4 |

|

other |

24 |

19 |

It is worth noting that enforcement practices regarding this article evolved in 2024. The percentage of charges related to the dissemination of political materials decreased, while the number of sanctions for ethnic xenophobia and religious-related content increased.

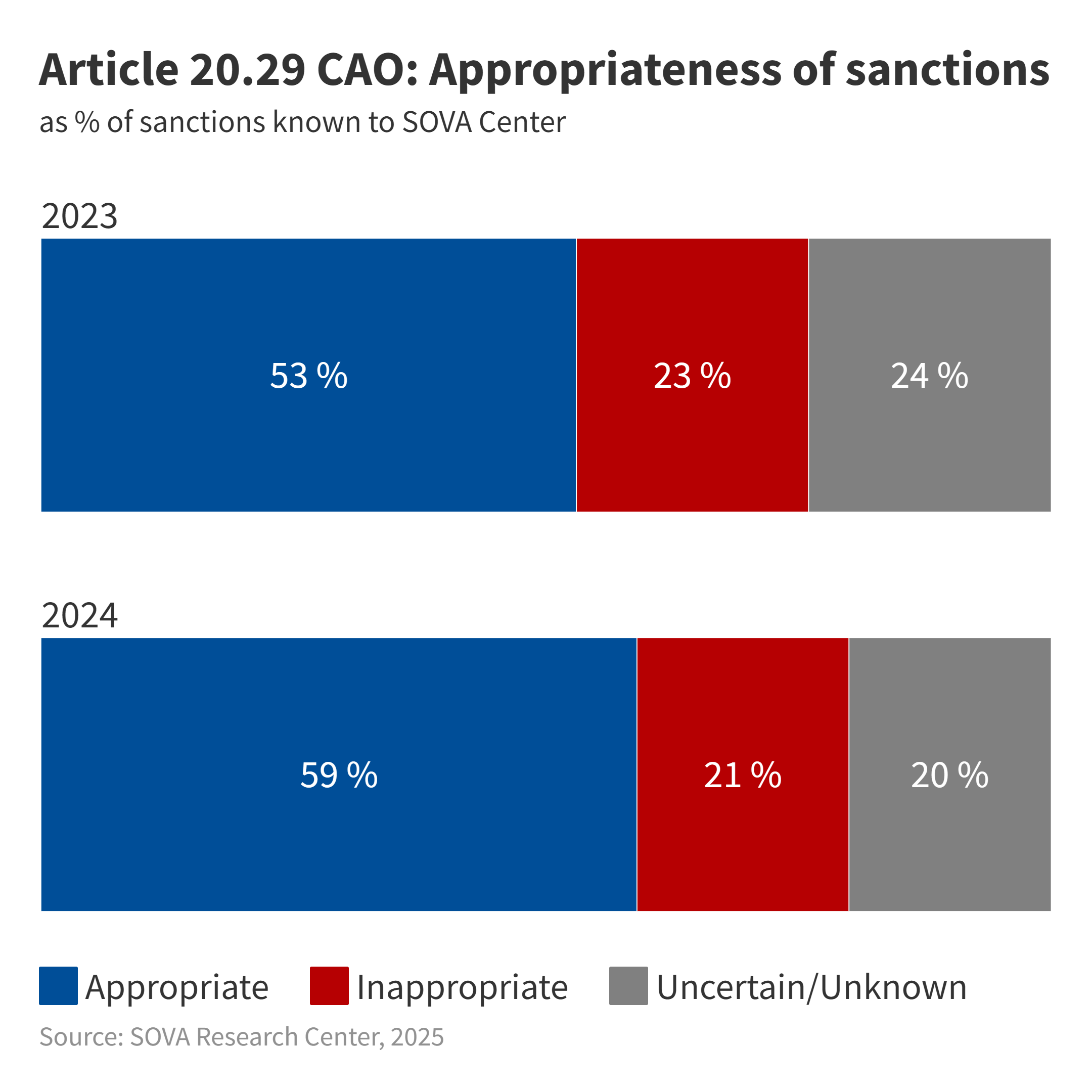

We categorized sanctions for the distribution of ethnic xenophobic materials and materials of militant Islamic groups as appropriate, sanctions for the distribution of peaceful religious and political materials as inappropriate, and in other cases, our assessment depended on the context and nature of the materials, if known. As a result, our assessments of the court decisions recorded in our database are distributed as follows.

Conclusion

Let us now address some general results of our calculations. In 2023, a total of about 8,130 sentencing decisions were issued under the CAO articles of interest to us. In 2024, there were about 8,165 such decisions, so, in general, the situation remained virtually unchanged (2022 was the “record” year, when the total number of sanctions under these articles reached about 10,630, while in 2021 the corresponding number was under five and a half thousand).

Meanwhile, if we compare 2024 to 2023 focusing on specific articles, we see a significant increase of sanctions under Article 20.3 CAO for displaying prohibited symbols (by 12 %) and under Article 20.3.1 for inciting hatred (by 15 %), with a continuing decrease in sanctions under Article 20.3.3 for discrediting the military and officials and Article 20.29 for distributing extremist materials (24 % drop in both categories).

In 2023, 93 % of those punished under the articles of interest to us were sentenced to a fine, 6 % were placed under administrative arrest, and the remaining 1 % mostly faced community service. The warnings accounted for about 0.1 %. In 2024, the percentages changed slightly: 91 % of sanctions were fines, 8 % arrests, community service accounted for 1 %, and warnings comprised 0.2 %.

In both 2023 and 2024, about two dozen officials, about a dozen individual entrepreneurs, and the same number of legal entities faced sanctions. All other punished offenders, that is, the overwhelming majority, were individuals.

We believe that sanctions related to the articles of interest to us were imposed for online activities in approximately 77 % of cases (6,260) in 2023 and around 82 % of cases (6,695) in 2024, indicating an increase in their usage. Our observations over the past few years show that most cases were based on posts made on VKontakte, with fewer instances on Odnoklassniki, public channels and groups on Telegram or WhatsApp, and occasionally on YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook. Accordingly, sanctions for offline activity were imposed in 23 % of cases (1,870) in 2023 and 18 % of cases (1,470) in 2024. Our calculations are imprecise, but we can assume that no significant changes in law enforcement have occurred in this respect.

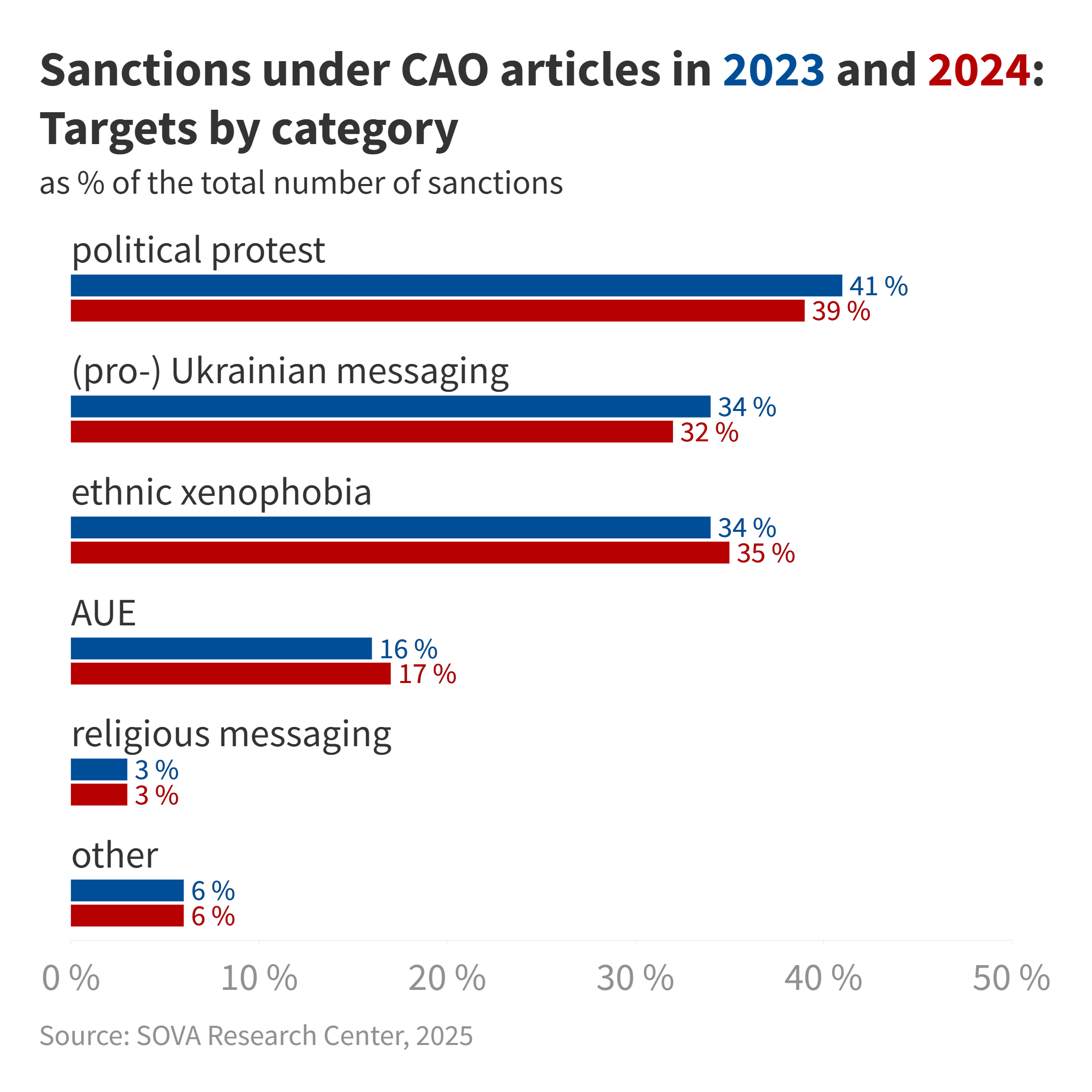

If we group the cases by categories of incriminating statements, the overall situation is as follows (remember that the categories overlap):

- cases based on protest political statements, distribution of prohibited opposition materials, and display of symbols in the context of a political protest: 41 % in 2023, 39 % in 2024;

- cases involving statements related to events in Ukraine or the display of Ukrainian symbols: 34 % in 2023, and 32 % in 2024;

- cases related to statements expressing ethnic xenophobia, display of Nazi symbols, and distribution of ultra-right materials: 34 % in 2023, 35 % in 2024;

- cases involving AUE symbols and materials: 16 % in 2023, 17 % in 2024;

- cases related to inciting religious hatred, displaying symbols of religious organizations, or distributing religious materials: 3 % in both years;

- other cases, including unspecified charges: about 6 % in both years.

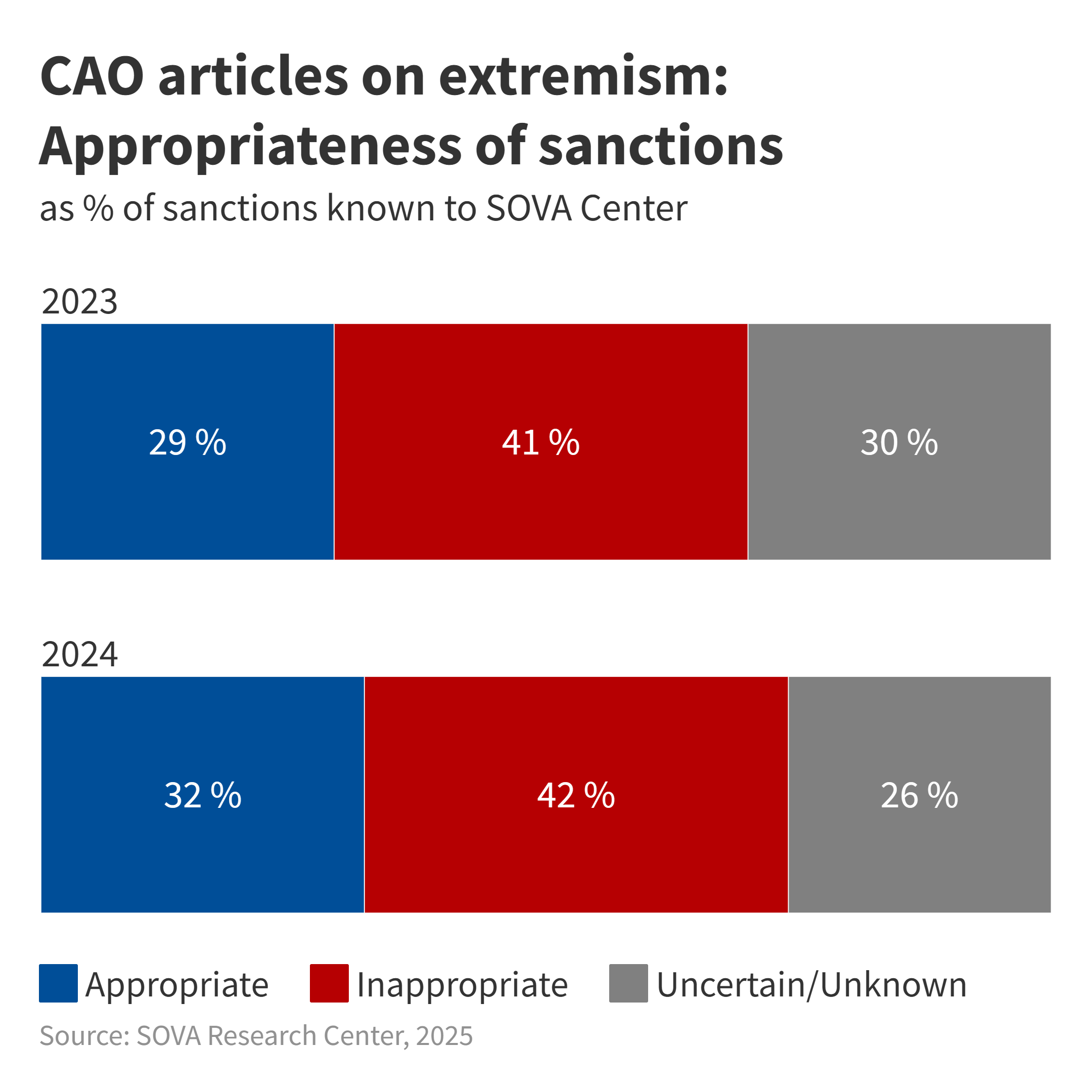

The graph below illustrates the relationship between the number of court-imposed sanctions that SOVA Center deemed generally appropriate, those we consider inappropriate restrictions on the right to freedom of expression that have no place in a democratic society, and those we were unable to evaluate unambiguously.

As the data indicates, there have been no significant changes in the appropriateness of sanctions, in our opinion, during 2023–2024.

[1] Judicial Statistics Data, Judicial Department of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation. 2025. March (https://cdep.ru/?id=79).

[2] Information on the activities of federal courts of general jurisdiction, published by the State Automated System “Pravosudie” (https://sudrf.ru/index.php?id=300).

[3] Data by OVD-Info, OVD-Info. Independent human rights media project. 2025. March (https://data.ovd.info/).

[4] The prior administrative punishment mechanism stipulates criminal responsibility for a repeated offence within a year from the imposition of the corresponding administrative punishment.

[5] See, for example, an overview of the discussion on the preliminary administrative punishment mechanism and its features here: Novikova E.V. “Administrativnaya preyuditsiya: diskussiya prodolzhayetsya,” Vestnik universiteta im. O.Ye Kutafina (MGYUA), No. 12 (2018) (https://vestnik.msal.ru/jour/article/view/656).

[6] We try to track the application of several more articles of the CAO, but the scale of their application is negligible. For example, Article 13.48 CAO (publicly equating the goals, decisions, and actions of the USSR and Nazi Germany during World War II), according to statistics from the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court’s was applied twice in 2023 and three times in 2024.

[7] For some reason, since 2022, the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court has been publishing the aggregated number of offenders punished under Articles 20.3 and 20.3.1 CAO. However, we provide separate statistics for each norm. To estimate them, we took the number of sentencing decisions issued by Russian courts under the two articles, as provided by OVD-Info. We then added these numbers together and calculated the percentage contribution of each article to the total. For both 2023 and 2024, Article 20.3 accounted for 81% of the total, while Article 20.3.1 comprised 19%.

[8] Except in cases of political criticism, see below.

[9] Including dark-skinned people, Roma, and Ukrainians. It should be noted that in 2023 we recorded five sentencing decisions for inciting hatred towards Ukrainians; there were only two in 2024.

[10] Article 20.3.3 Part 2 CAO penalizes discrediting the actions of the army and government agencies abroad, accompanied by calls for public actions without a permit or by a threat of various harm.

[11] Article 20.25 CAO provides for administrative arrest or community service in the event of non-payment of a fine issued for an offence.

[12] “Pit Bull” Nazi skinhead organization recognized as extremist, SOVA Center. 2010. September 14 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2010/09/d19739/). For more information on charges for pit bull stickers, see: More fines for pit bull stickers in Dagestan, SOVA Center. 2024. April 9 (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2024/05/d49621/).