Summary

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence : Attacks against Ethnic

“Others” : Attacks against

Ideological Opponents : Other Attacks : Racism among Soccer Fans

Crimes against Property

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

Crime and punishment statistics

This report by SOVA Center[1] is focused on the phenomenon known as hate crimes – that is, on ordinary criminal offenses committed on the grounds of ethnic, religious or other similar enmity or prejudice[2], and on the efforts by the state to counteract them.

This is our second year of issuing the report in this format. Previously, the chapters on hate crime were part of a single large annual report encompassing both criminal and political activities of nationalists, and all measures to counteract them.

Summary

According to the monitoring data of SOVA Center, the number of racist and neo-Nazi motivated attacks remained relatively small in 2018 and, possibly, has even continued to decline. We assume that this decline is due primarily to the drop in the attacks against “ethnic outsiders.” The trend does not hold for “ideological opponents,” if we take into account the attacks by pro-government nationalists against those viewed as the “fifth column” (including a rather exotic incident of Cossacks beating up the rally participants with their nagaika whips). We also recorded an unexpectedly large number of attacks against the homeless, although most of these were violent attacks are documented in a single video created by the neo-Nazis, who called themselves “the orderlies” (sanitary).

In recent years, we have observed repressive state policies actively applied to classic racist hate crimes and to neo-Nazi groups in general. This development was partially related to the events in Ukraine and, in 2018, related also to the preparations to and hosting of the FIFA World Cup. As a result, ideologically motivated violence has not been growing; it might even be in decline and is obviously shifting to different groups of victims – the ones, whom the state is less inclined to protect for one reason or another. There is a widespread suspicion that the authorities, in fact, approve of such violence against certain groups (the so-called “fifth column”).

The activity levels of vandals motivated by religious, ethnic, or ideological hatred have also declined. However, this drop is likely explained by the disappearance of a popular target – Jehovah's Witnesses buildings – that have all been confiscated.

As for the law enforcement practice, the number of people convicted for hate-motivated attacks was higher than a year earlier. In general, legal qualifications in sentencing have been improving in this law enforcement area. The only issue that raised serious doubts was the qualification in the sentence to Alexander Zenin, the organizer of the murder of anti-fascist Timur Kacharava. The number of offenders convicted for crimes against property has decreased, but the dynamics here are unstable, probably due to the dual nature of such crimes and the possibility of classifying them under Article 282 of the Criminal Code.

We see that hate crimes have been kept at a relatively low level in recent years, the law enforcement in this area has reached a certain, quite decent, level of efficiency. However, no further significant improvement has occurred. Of course, it can be argued that this observed stagnation is due to the impossibility of complete eradication of an entire category of crimes, but we assume that the latency of hate crimes still remains high, and there is still considerable space for progress in the spheres of investigation and legal qualification.

Systematic Racist and Neo-Nazi Violence

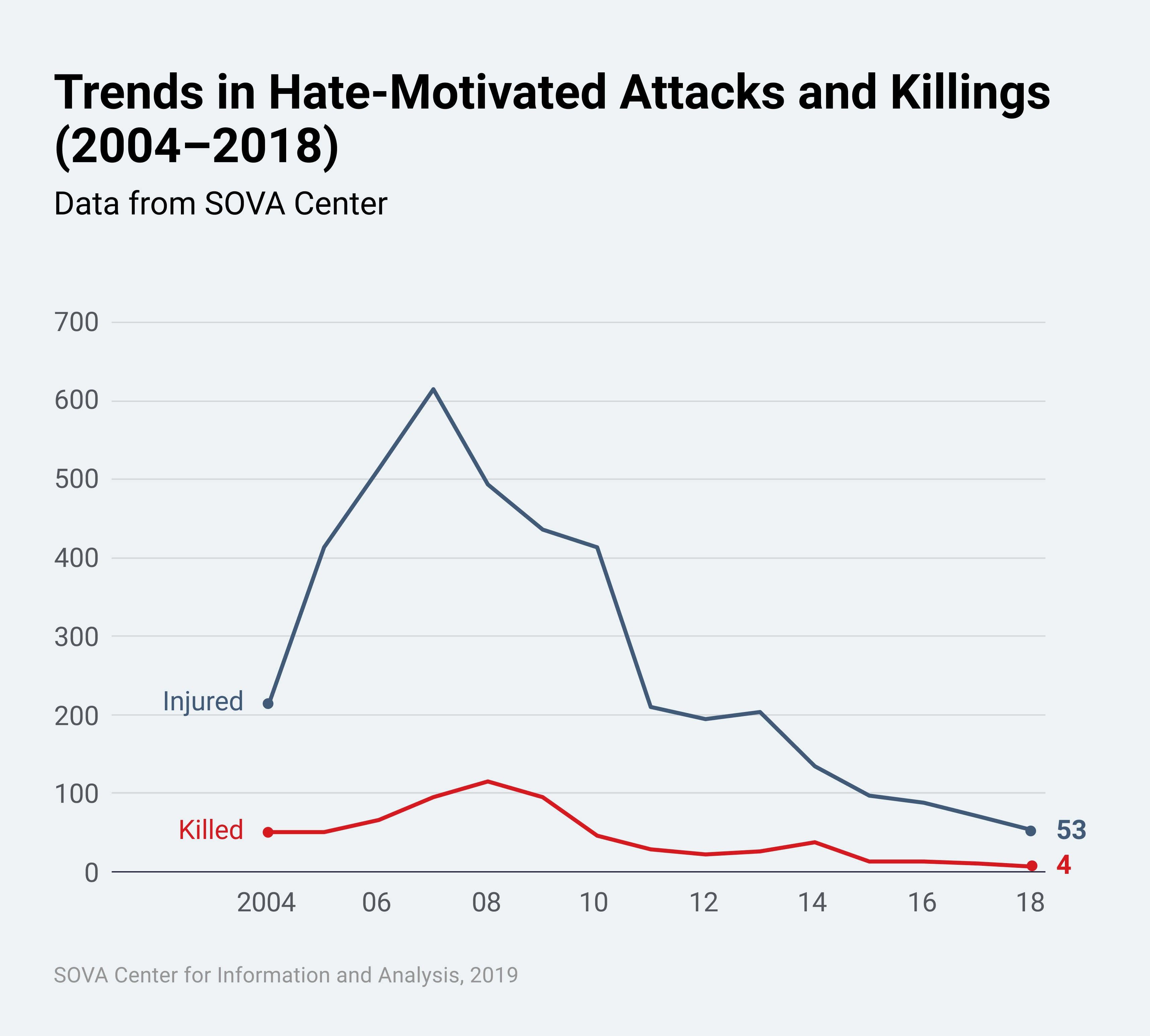

At least 57 people suffered from racist and other ideologically motivated violence in 2018; at least 4 of these died, the rest were injured. These numbers do not include the victims in the republics of the North Caucasus and in the Crimea, where our methods, unfortunately, are not applicable. Our statistics continues to indicate a decrease in the number of serious ideologically motivated attacks – 9 people died, 69 were injured in 2017.[3] Of course, our 2018 data is still far from final, and, unfortunately, these numbers will inevitably grow,[4] since, in many cases, the information only reaches us after a long delay.

It should be borne in mind that data collection is becoming increasingly difficult year after year. Russia collects no official statistics on hate crimes. In the last few years, the media either fails to report such crimes at all, or describes them in such a way that a hate crime is almost impossible to identify. For example, for the past several years, the St. Petersburg media outlets have been reporting dead bodies of migrants with knife wounds found on the streets. The reports consist of one short line without any details, so we are unable to make any inferences about the circumstances of these people’s deaths. Victims are also not at all eager to publicize their incidents; they rarely report attacks to non-governmental organizations or the media, let alone the police and law enforcement agencies, since they expect such complaints to result in very little help and almost inevitably cause problems. Meanwhile, attackers, who used to brag about their “achievements” online, have grown more cautious in the wake of more active law enforcement pushback and widely publicized trials of the ultra-right militants in recent years. Quite often, we only learn about the incidents several years after the fact.

Thus, our quantitative conclusions are purely preliminary, and it might be possible that, in the end, we will be seeing a small increase in the number of victims, rather than the current small decrease. Evidently, it would be more accurate to say that the number of victims has remained fairly stable over the past four years (see the table in the Appendix). This number is, of course, an order of magnitude lower than it was a decade ago, but still, the current level of ideological violence cannot be deemed insignificant.

The attacks of 2018 occurred in 10 regions of the country (vs. 20 regions in 2017. The levels of violence in Moscow (2 killed, 28 injured) and St. Petersburg (1 killed,[5] 10 injured) traditionally top the list.

In 2018, a number of regions disappeared from our statistics (the Belgorod, Kirov, Orenburg, Oryol, Rostov, Tula, Chelyabinsk, Yaroslavl, Trans-Baikal, Krasnodar, Perm and Khabarovsk regions, the republics of Mari El, Mordovia and Tatarstan), but on the other hand, crimes were reported in several new places, which were not on our radar in 2017 (the Kaluga Region, the Kursk Region, the Tyumen Region and the Samara Region).

According to our data, besides Moscow, St. Petersburg and the Moscow Region, the centers of racist violence for the last ten years can also be found in the Volgograd, Voronezh, Kaluga, Novosibirsk, Samara, Sverdlovsk and Trans-Baikal regions, and the Republic of Tatarstan. Relevant crime reports appear in these regions almost every year. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the law enforcement agencies of these regions are simply better at communicating with the public and the media and provide more complete information about the situation.

Attacks against Ethnic “Others”

People, perceived by their attackers as “ethnic outsiders,” still constituted the largest group of victims, although their numbers have been decreasing year after year. We recorded 20 ethnic attacks motivated by ethnic considerations in 2018. In 2017, we reported 28 such victims.

Victims in this category include migrants from Central Asia (2 killed, 3 injured vs. 11 injured in 2017), dark-skinned people (1 person injured, same as in 2017),[6] and individuals of unidentified “non-Slavic appearance” (12 injured vs. 7 injured in 2017), who, most likely, were also from Central Asia, since their appearance was described as “Asian” by eyewitnesses. Attacks against other “ethnic outsiders” accompanied by xenophobic slogans were reported as well. For example, a beating of a person, accompanied by anti-Chinese slurs, took place in Moscow.

In addition to the street attacks, we encountered several cases of group attacks in the subway and commuter train cars. For example, in June 2018, three videos from the so-called “white car” campaign appeared on the Internet; they show groups of aggressive young people beating up commuter train passengers of “non-Slavic appearance.”[7]

The level of ordinary xenophobic violence remains unknown even approximately. These cases are usually qualified by the media and law enforcement agencies as incidents of ordinary hooliganism. Nevertheless, three to five such incidents are reported per year. Incidents such as the swastika and offensive statements found on the car of a migrant from Tajikistan or xenophobic graffiti on the pavilion owned by a migrant from Uzbekistan eloquently testify to the presence of xenophobic attitudes in Russian society.

The events that took place in August 2018 in the village of Urazovo in the Belgorod Region illustrate such prejudices even more vividly. About 150-200 Roma residents left the village in fear of pogroms. Their concerns proved to be justified. On the following day, several houses in the village, in which Roma families used to live, were set on fire. The flight and the arson were triggered by detention of a Roma man on suspicion of rape and murder of a nine-year-old local girl.[8]

Attacks against Ideological Opponents

The number of attacks by the ultra-right against their political, ideological or “stylistic” opponents increased slightly in 2018 bringing the number of injured victims to 14 (vs. 3 dead and 9 injured in 2017).[9]

This group of victims included representatives of youth subcultures – politicized (anti-fascists and individuals perceived as anti-fascists) as well as the ones with no specific political views (rappers, punks).

The victims of beatings in this group also included the individuals perceived by their attackers as the “fifth column” and “traitors to the Motherland,” such as protest participants and people standing guard at the Boris Nemtsov memorial. There were 4 such attacks in 2018, compared to 6 attacks in 2017. Nationalist pro-Kremlin groups, whose representatives that take part in such attacks, include, most prominently, the NOD (Natsionalno osvoboditelnoe dvizhenie, National Liberation Movement) and the SERB (South East Radical Block) led by Gosha Tarasevich (Igor Beketov).[10] In addition to assaults and provocations against the picketers, the attackers also targeted the offices of alleged “traitors.” Thus, in a single month of October, the SERB activists attacked the office of Lev Ponomarev’s “For Human Rights” movement twice.

The two groups named above are not the only ones, whose representatives are known to have used violence against the opposition. A particular incident, which took place on May 5, received significant media attention. During Alexei Navalny’s “He is Not Our Tsar” protest, people in Cossack uniform showed up and started beating up the event participants, also using their nagaika whips. The Cossacks of the Central Cossack Troops (Tesntral’noe Kazach’e Voisko) later confirmed that they had been present on Tverskaya Street during the action. However, the attackers also included the NOD activists dressed in camouflage uniforms and carrying a flag;[11] they snatched protesters from the crowd and dragged down the opposition activists, who were trying to climb onto the pedestal of a monument.[12]

The anti-Ukrainian rhetoric of recent years has also been bearing fruit. Attacks against Ukrainians are quite rare, apparently due to the fact that ethnic Ukrainians are hard to identify in a crowd. However, politicized anti-Ukrainian incidents do occur. Last year, we recorded two attacks related to the display of the Ukrainian flag. Both incidents took place in St. Petersburg. In one case, a passer-by attacked the activists of the St. Petersburg Solidarity and Democratic Petersburg movements, who were returning from the rally, carrying posters and unfurled Ukrainian flags.[13] The other incident was an attack against an activist of the Solidarity movement, who was standing in a solitary picket on the Anichkov Bridge with a Ukrainian flag and the poster “Freedom to the Political Prisoner.”[14]

The Internet page of the Russian Imperial Movement (Russkoie Imperskoie Dvizhenie, RID) and in the online group “Veterans of Novorossiya” published threats against artist Sergey Zakharov, “a Kiev character distinguished by his anti-Russian and anti-DNR position.” The nationalists called on their audience to come to the Sakharov Center (which conducted the festival “Muse of the Recalcitrant” and presented Zakharov’s works)[15] on May 1 for a “preventive conversation”. As a result, on May 1, several dozen people – including some men in Cossack uniform, some activists from the Lugansk People’s Republic, several members of the Donbass Volunteers Union and SERB activists – tried to break into the Sakharov Center and started a fight.[16]

The issue of threats by the far right has never left the agenda throughout the year. In addition to the episodes mentioned above, ultra-right websites have published photographs, personal data and threats targeting independent journalists, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and judges presiding over the nationalists’ trials. In some cases (the Dina Garina case),[17] the emphasis was placed on the “non-Russian names and surnames” of their relatives.

Threats against the “traitors” – defendants in group trials related to racist attacks, who testified against their “comrades-in-arms” –took place as well. Their personal information was published on the Internet. The actions were not limited to threats. The far-right Internet sites also posted video clips with scenes of brutal beatings. The Firstline Nevograd movement (a St. Petersburg neo-Nazi movement, allegedly under the leadership of Andrei Link) published a video of a young man lying on the ground bleeding, being kicked by his attackers. The video included an explanation that the movement had “found a rat” – the victim “leaked information using his position in the group... and committed impermissible acts.”

Other Attacks

The number of attacks against the LGBT was smaller than in the preceding year – 1 killed,[18] 5 injured (vs. 11 injured in 2017). However, we have to emphasize that our data is minimal (as was the case with our general statistics), and the real level of homophobic violence is not known and is, most likely, much higher.[19] The victims in 2018 included the LGBT conference volunteers in Moscow, a young woman beaten up near a gay club in Yekaterinburg, and the participants of the LGBT pickets in Volgograd, beaten up by Cossacks, who were also yelling “There should be no gays in Volgograd.”

14 attacks against the homeless were recorded in 2018 (1 killed, 13 injured vs. 4 killed and 1 injured in 2017). We learned about these victims on October 30, 2018, when the links to two videos appeared online. The videos were made by neo-Nazis[20] and contained the scenes of murders and attacks against at least 15 people; the victims were mostly drunk or drug-impaired. The publishers of the videos call themselves “the orderlies” (sanitary) and mention a certain “Project Sanitater-88.” The videos show the attackers beating the victims, cutting them with knives, and spraying them in the face. The time and place of filming are impossible to determine for most of the episodes, but we assume that these attacks took place in 2018. So, our data for this category of victims is quite preliminary.

Official media outlets point out that teenage attacks on the homeless have become widespread,[21] but no statistics is publicly available on this topic. Moreover, when deceased homeless people are discovered, the cause of their death and the motive for the attacks are hard to determine. For example, a homeless person died from multiple stab wounds in Chelyabinsk in August 2016, and, only in September 2018, it was reported that the investigation had qualified this attack as a hate murder, and that two right-wing activists Maxim Sirotkin and Nikita Yermakov from the ultra-right movement Misanthropic Division (recognized as extremist back in 2015) were the defendants in this case.[22]

In 2018, there was almost no mention of any attacks motivated by religious hatred. This state of affairs could possibly be explained by the fact that the leadership of Jehovah's Witnesses, preoccupied by the flood of criminal cases, no longer publishes information on the attacks against their co-religionists – these attacks used to constitute the overwhelming majority of cases in this category. In any case, the number of such attacks has now dropped – the Witnesses have no buildings left, and they cannot engage in open missionary work, so typical situations, in which violent attacks used to occur, no longer happen. We know of only one incident, in which a dispute about the proper way of wearing a cross took place in the subway and ended with serious stab wounds.[23]

Individuals, who tried to intervene and defend others from being beaten up or expressed their disapproval of the aggressive young people’s behavior, also became part of our unfortunate statistics. For example, on the night of August 31 / September 1, 2018, at the Mendeleevskaya Metro Station in the Moscow, a young woman rebuked a group of young men, who were loudly singing “Moscow Skinheads,” a song by the ultra-right band Kolovrat. One of the “soloists” started hitting her in the head and yelling neo-Nazi slogans. When another passenger stood up for her, the attacker began to threaten him with a knife. After sharing her experience on Facebook, the victim started receiving threatening personal messages “You didn’t get enough; we’ll add some more!”[24]

Racism among Soccer Fans

In connection with the FIFA World Cup in the summer of 2018, law enforcement agencies were paying special attention to the racist antics of soccer fans. In July 2017, the Russian Football Union (RFU) presented a monitoring system for matches, and this system, indeed, has been accurately identifying the incidents of racism at stadiums.[25] According to the data of the SOVA Center and the Fare network, the total number of discriminatory incidents has dropped during the 2017–2018 season. The number of recorded cases of displaying ultra-right banners at stadiums has shown a particularly dramatic fall. However, after a period of relative quiet, the frequency of discriminatory chants has increased. The chants in question include the racist “hooting,” neo-Nazi slogans, and the outbursts against the natives of the Caucasus region.[26]

The racist shouting incident also occurred during the World Cup. On June 16, 2018 in Moscow, a soccer fan yelled “Denmark, White Power!” at the Danish fans, who, at that time, were giving interviews to Eurosport journalists.[27] Xenophobic statements from the fan stands were also heard once the World Cup was over. For example, Spartak fans started chanting racist slogans directed at the Brazilian-born Lokomotiv goalkeeper Marinato Guilherme during a match at the Otkritie Arena stadium in Moscow on December 2, 2018.[28]

The problem of hate-motivated attacks committed by Russian ultra-right soccer fans has also persisted. In 2018, we know of three attacks involving soccer fans, which appear ideologically motivated. The actual number of such physical attacks by soccer fans might be higher, given the aggressiveness of the milieu.

Crimes against Property

Crimes against property include damage to cemeteries, monuments, various cultural sites and various property in general. The Criminal Code qualifies these cases under different articles, but law enforcement is not always consistent in this respect. These actions are usually referred to as vandalism, and we used to group them under this term as well, but then, about a year ago, decided to abandon this naming convention, since the concept of “vandalism” (not only in the Criminal Code, but in the language in general) clearly fails to encompass all possible actions against property.

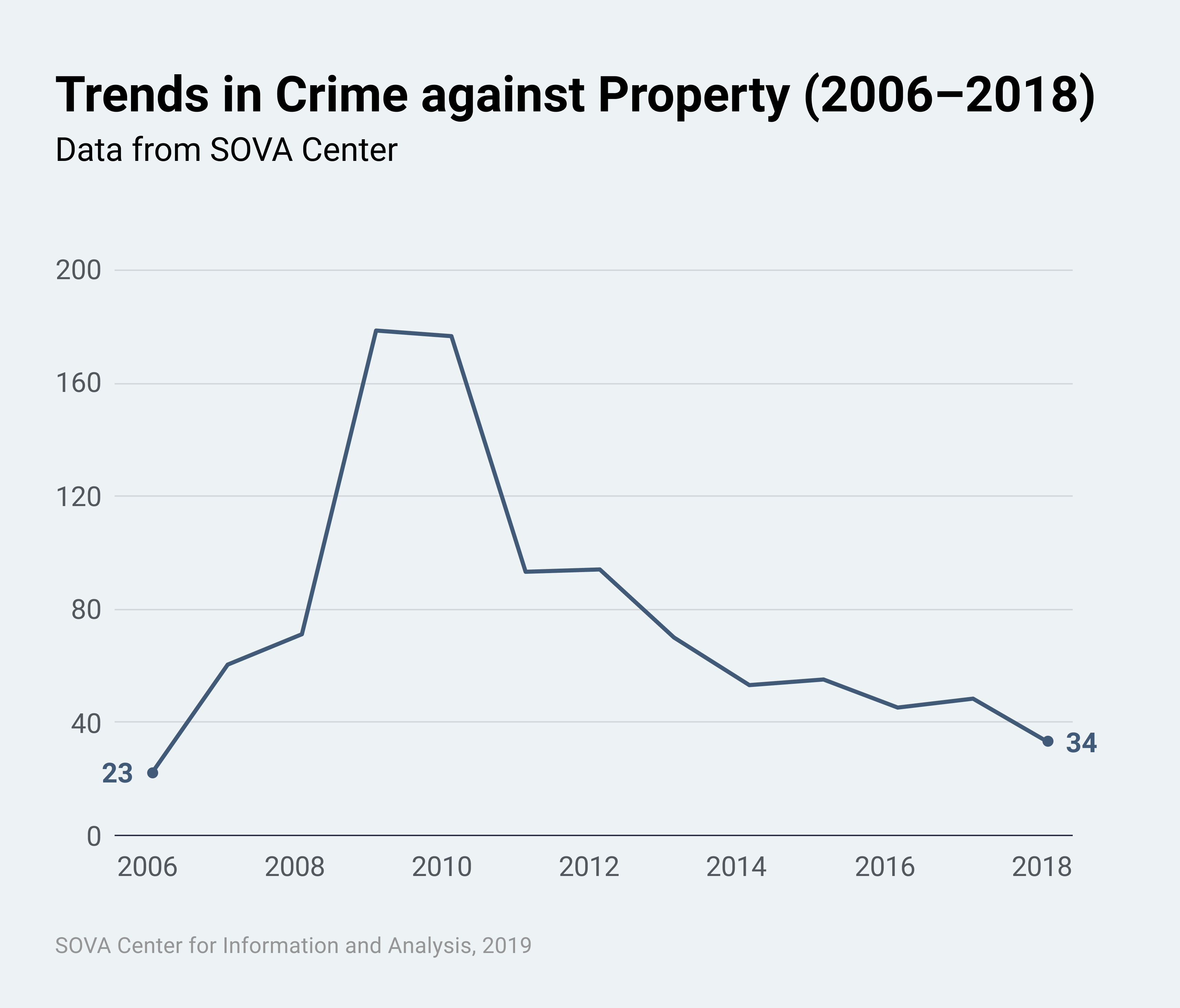

In 2018, the number of such crimes motivated by religious, ethnic or ideological hatred was significantly lower than a year earlier – there were at least 34 incidents in 23 regions of the country in 2018 vs. at least 49 in 26 regions in 2017. The majority of these actions continue to be directed against religious objects. Our statistics traditionally does not include isolated cases of neo-Nazi graffiti and drawings found on houses and fences.

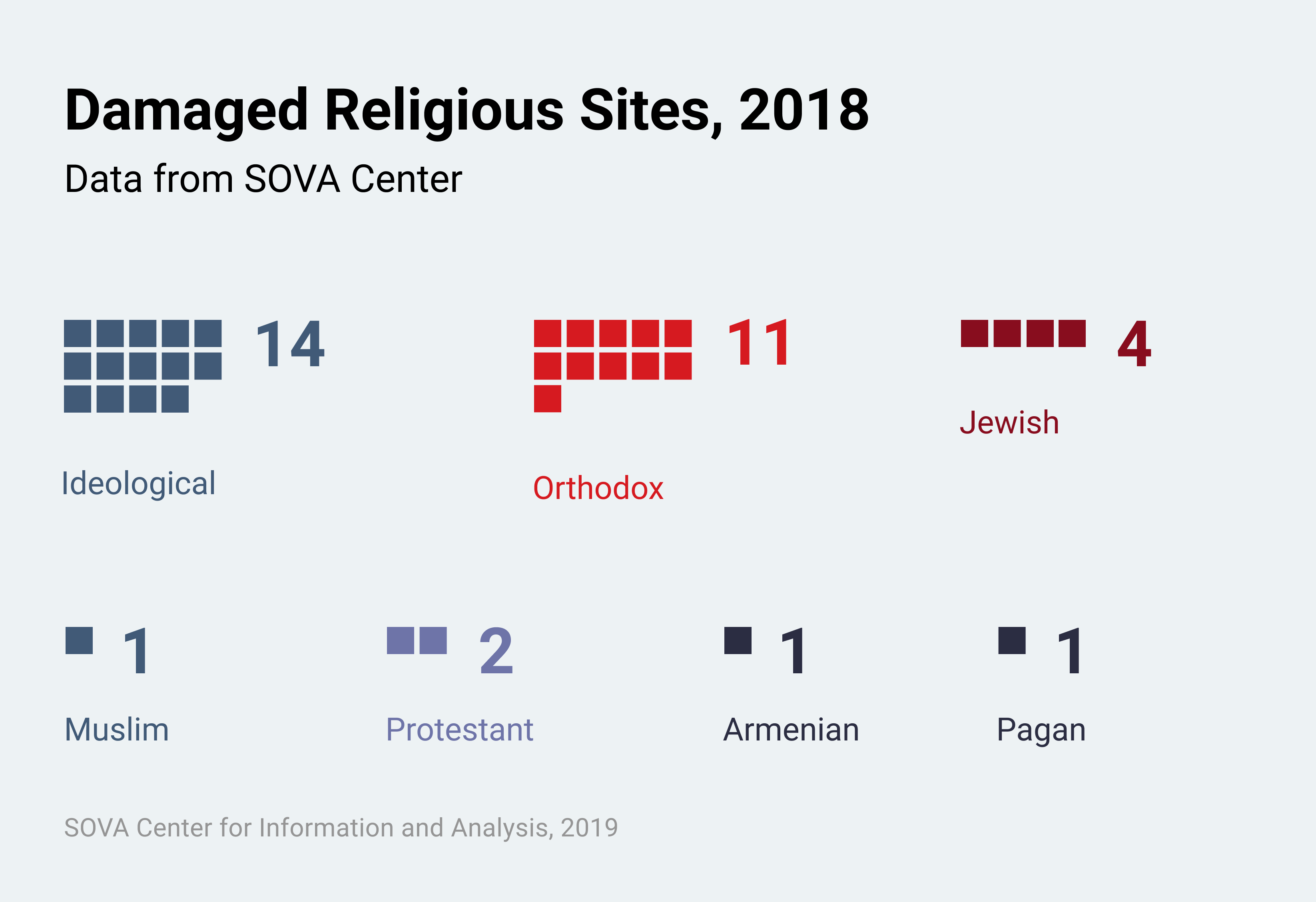

Fewer ideological objects suffered in 2018 – the number is 14 compared to 18 episodes in 2017. Unknown perpetrators defaced with graffiti the WWII Victory monument, the obelisk in memory of the young victims of the concentration camps, the monument to the Cheka officer Xenia Ge, the Immanuel Kant’s grave and monument, and so on. Another set of broken and destroyed objects was associated with ideological opponents of the ultra-right and included Ksenia Sobchak's office in St. Petersburg, and memorials to deceased American rapper XXXTentacion.

The number of affected Orthodox Christian churches and crosses turned out to be almost on par with ideological objects – 11 incidents, 4 of which were arson (in 2017, there were 11 incidents as well). Jewish objects took the third place with 4 incidents, 2 of them arson (vs. 1 incident a year earlier). 2 incidents were related to Protestant sites (there were 2 in 2017 as well). Muslim, Armenian and pagan objects suffered 1 incident each (in 2017, there were 2 episodes related to pagan sites, and no information about any damage to Muslim or Armenian sites).

However, sometimes the perpetrators’ ignorance takes comic forms and creates problems with classifying the damaged object for our purposes. Thus, in February 2018, unknown persons painted a swastika on a monument to the Russian-Armenian friendship in Novokuznetsk (the Kemerovo Region); the swastika was accompanied it an explanation – “To Jews.” Apparently, the attackers mistook the Armenian alphabet for Hebrew[29].

Overall, the number of attacks against religious sites has decreased. There were 20 such incidents in 2018 (we reported 30 both in 2016 and in 2017), apparently due largely to the disappearance of an entire class of objects – Jehovah's Witnesses buildings. The percentage of the most dangerous acts – arson and explosions – also decreased in comparison with the preceding year. In 2018 it comprised 20%, that is, 7 out of 35 (a year earlier the most dangerous acts comprised 29% or 14 out of 49), possibly for the same reason.

The geographic distribution has changed as well. In 2018, such crimes were reported in 10 new regions (the Novosibirsk, Ryazan, Samara, Ulyanovsk, Yaroslavl and Stavropol Regions, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous District, the Republics of Karelia and Khakassia, and Crimea). On the other hand, 13 regions, previously on this list, have now disappeared from our statistics (the Arkhangelsk, Volgograd, Vologda, Jewish Autonomous, Irkutsk, Lipetsk, Moscow, Penza, Rostov, Ulyanovsk, Trans-Baikal and Krasnoyarsk Regions, and the Komi Republic).

In Moscow and St. Petersburg, as well as in the Arkhangelsk, Voronezh, Kemerovo, Leningrad, Murmansk, Sverdlovsk, Tula and Chelyabinsk regions and in the Republic of Tatarstan (that is, in 11 regions total) such crimes were reported in both 2017 and 2018.

The geographic spread for xenophobic vandalism turned out to be wider (23 regions) than that for acts of violence (10 regions). 5 regions reported both problems (vs 7 regions a year earlier): Moscow, St. Petersburg, the Novosibirsk Region, the Samara Region and the Sverdlovsk Region.

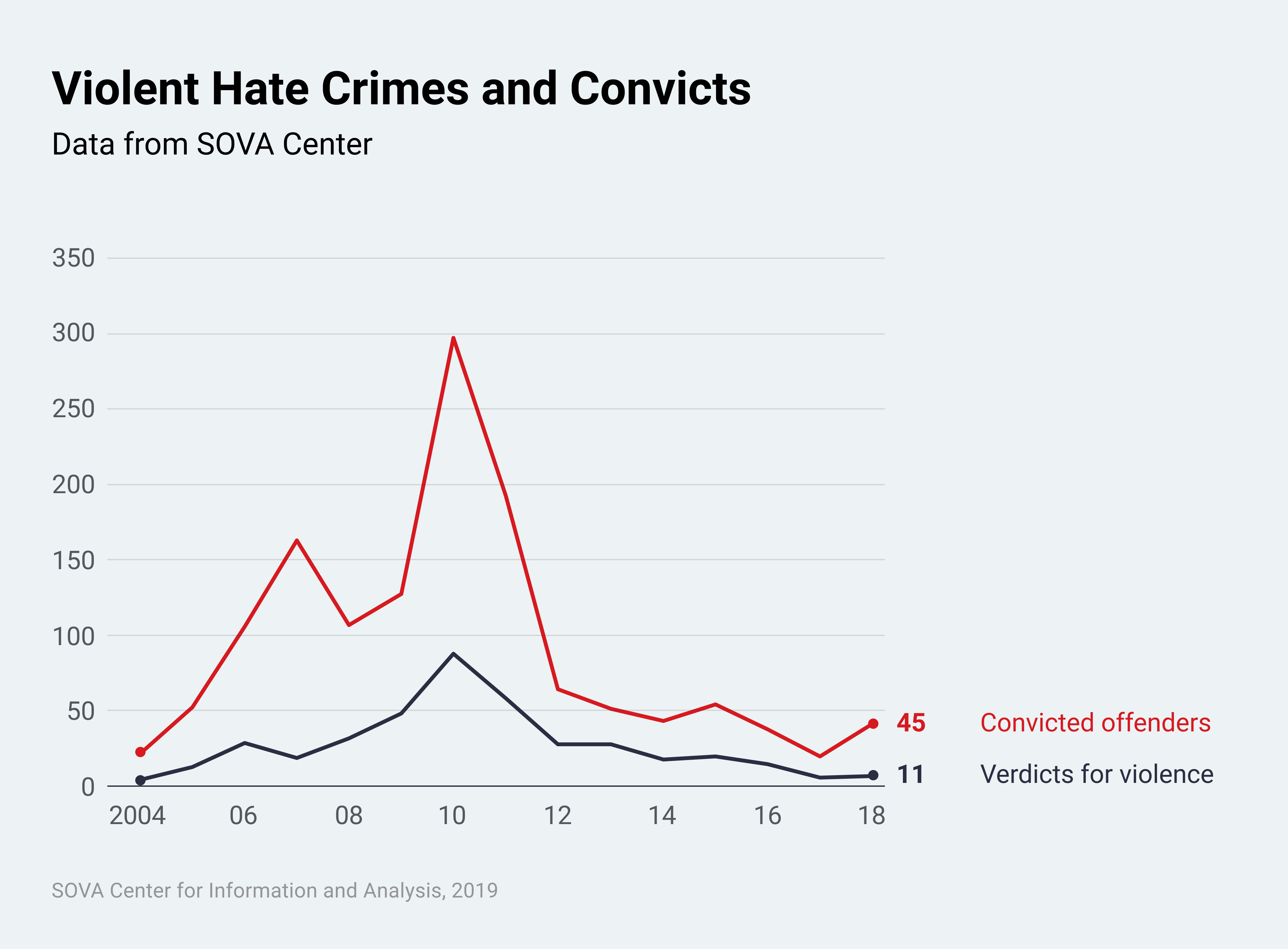

Criminal Prosecution for Violence

In 2018, the number of people convicted of violent hate crimes was higher than in the preceding year. In 2018, at least 11 convictions, in which the courts recognized a hate motive were issued in 11 regions of Russia (vs. 10 sentences in 9 regions in 2017).[30] In these proceedings 45 people were found guilty (vs. 24 people in 2017).

Racist violence was qualified under the following articles that contain the hate motive as an aggravating circumstance: murder, threat of murder, intentional infliction of severe, moderate and light bodily harm, hooliganism, and battery. This set of articles has remained almost constant over the past six years. Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“incitement to hatred”) in relation to violent crimes appeared in 5 convictions (vs. 7 in 2017), and in four cases it was used for specific instances of ultra-right propaganda (videotaping violence and publishing on the Internet), and not for violence per se.

In the last case, Alexander Zenin, who had been on the federal wanted list for 12 years on suspicion of complicity in the murder of Timur Kacharava on November 13, 2005,[31] was convicted under Article 282 Part 2 Paragraph “A” of the Criminal Code (“incitement to hatred with the use of violence”). The Smolninsky District Court of St. Petersburg sentenced Zenin to 1.5 years of imprisonment,[32] since Article 105 of the Criminal Code (“murder”) was dropped from the charges. The appropriateness of this sentence is questionable,[33] given that the victims and the investigation considered Zenin to be the organizer of the group attack (even if he did not specifically plan a murder), and given the fact that, taking into account his pre-trial detention (one day in pre-trial detention counts for 1.5 days in prison) and the subsequent month for filing an appeal, the offender most likely will never go to penal colony.

The verdict of the Babushkinsky court of Moscow against Maksim “Tesak” [Hatchet] Martsinkevich – the leader of the ultra-right social movement Restrukt! – is also worth mentioning, although the hate motive was not taken into account. Martsinkevich was sentenced to 10 years in a penal colony under Article 162 Part 2 of the Criminal Code (“robbery committed by a group of persons”) and Article 213 Part 2 of the Criminal Code (“hooliganism committed by a group of persons”) in the court case related to the attacks conducted under the pretext of combating drug trafficking as part of the Occupy Narcophiliai project. The other defendants in the case were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 2 years and 11 months to 9 years in a penal colony. The court released one person from custody due to the completion of punishment.[34]

We know that, in at least one case, the motive of hatred toward a “social group” was imputed. In addition to the exotic social groups of the past years, such as “Chinese Communists,”[35] “rock music fans,”[36] “Russian military,”[37] “volunteer police assistants,”[38] “psychiatrists,”[39] “men,”[40] “thugs” (gopniki),[41] etc., a new social group – “anime” – was discovered in 2018. This puzzling social group appeared in June 2018 in the verdict of the Central District Court of Novosibirsk in the case of the attack against an 18-year-old student by ultra-right teenagers. The law enforcement agencies qualified this case as group hooliganism with the motive of hatred toward the social group “anime” (Article 213 Part 2 of the Criminal Code). The court found both young people guilty. One of them received a suspended sentence of 2.5 years with subsequent 2.5 year probation period; the other one – a suspended sentence of 1.5 years with subsequent 2-year probation period.[42]

SOVA Center believes that the vague concept of “social group” should be excluded from the anti-extremist legislation altogether.[43] Moreover, in this particular case, the formula social group “anime” also provides no information as to the specific target of the teenagers’ hatred.

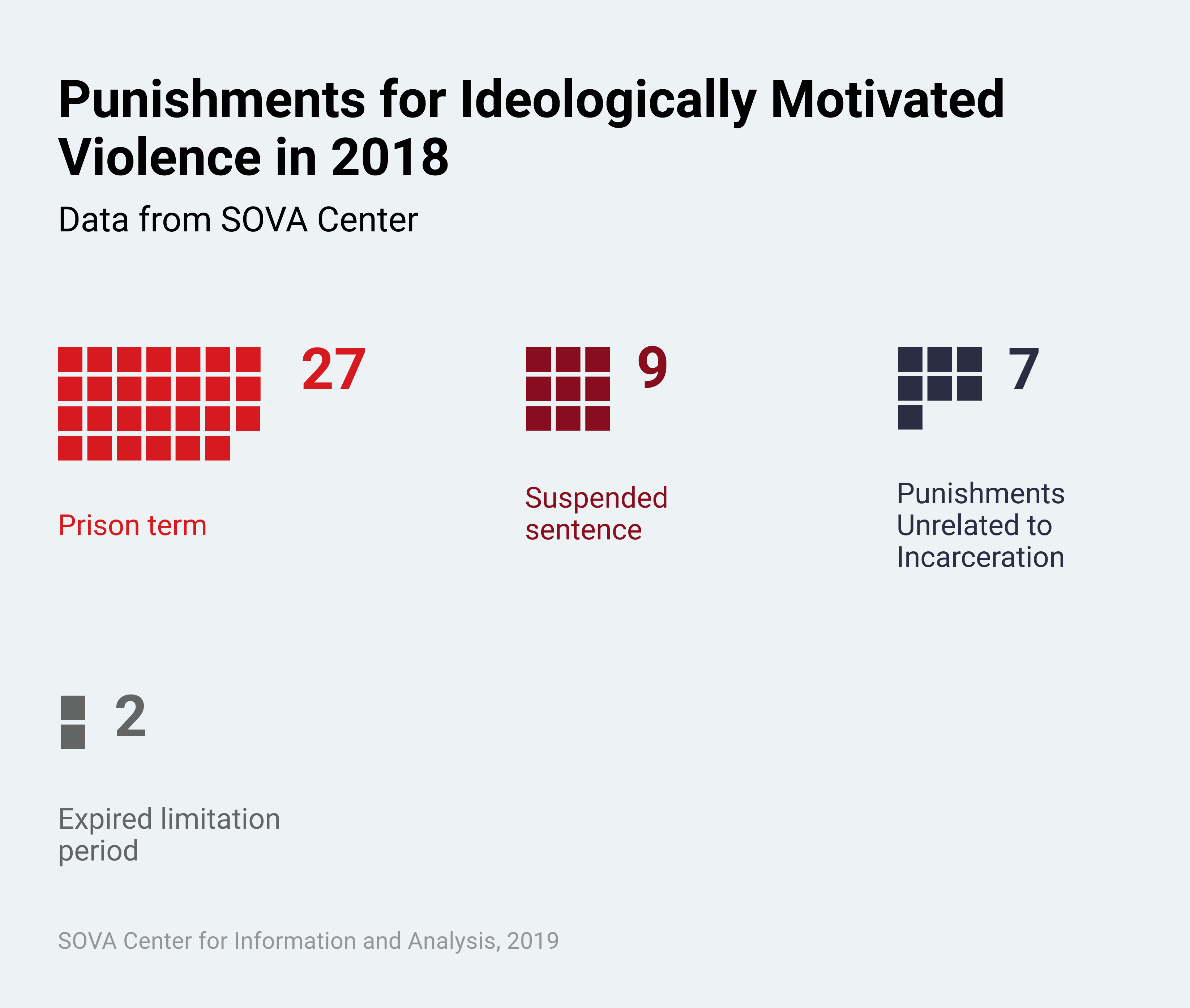

Penalties for violent acts were distributed as follows:

- 1 person was sentenced to life imprisonment;

- 3 people were sentenced to 15 – 20 years in prison;

- 1 person – to 10 – 15 years;

- 6 people – от 5 до 10 years;

- 12 people – to 3 – 5 years;

- 4 people – up to 3 years;

- 9 people received a suspended sentence;

- 2 people were sentenced to fines;

- 2 people – to correctional labor;

- 1 person – to community service;

- 2 people – to restrictions on freedom;

- 2 people were found guilty but released from punishment due to the expiration of the limitation period;

- 1 person was acquitted.

We only know of one convicted offender, who received an additional punishment in the form of having to pay compensation to his victims for material and moral harm. It is possible that other decisions on additional compensation were issued, but the official sources seldom report on them. We believe that this practice should be used more widely.

We also know of other additional penalties: 1 ban on the use of the Internet, and 3 additional fines.

As demonstrated by the above data, 20% of convicted offenders (9 out of 45) received suspended sentences in 2018, significantly exceeding the corresponding figures of 2016 and 2017.

Six individuals, who received suspended sentences, were defendants in large group trials (including members of the Misanthropic Division from Chelyabinsk). Perhaps, their direct participation in the violent actions could not be proved, or they made a plea bargain.

The suspended sentences for the above-mentioned teenagers from Novosibirsk, who had attacked an anime fan, were apparently related to their age (they are minors) and the fact that the student did not suffer serious injuries.

The suspended sentence imposed on the ultra-right activists in Rostov-on-Don for attacking the journalist Vladimir Ryazantsev from Kavkazsky Uzel (Caucasian Knot) is probably explained by the fact that the attack was qualified under the “light” Article 116 of the Criminal Code (“battery”), which does not entail severe punishment.

However, a suspended sentence to a resident of Kalmykia for attacking a 46-year-old Chechen woman, whom he had “grabbed by the hair, hit in the face with his knee, broke her nose, knocked out her teeth and kept beating with his fists and feet,” [44] seems to be incongruent with his crime.

We would like to reiterate that we are skeptical about suspended sentences for crimes related to ideologically motivated violence. Our observations over many years has shown that, in the overwhelming majority of cases, suspended sentences do not deter ideologically motivated offenders from committing such acts in the future.

More than half (26 of 45) of those convicted for violence were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment. One person in Chita was sentenced to life imprisonment for a series of crimes, including the murder of 8 people motivated by hatred on the basis of nationality.

Criminal Prosecution for Crimes against Property

Somewhat fewer sentences were issued for crimes against property in 2018 than in the preceding year. We know of 2 sentences issued in 2 regions against 6 people (vs. 3 sentences against 5 people in 3 regions in 2017).

In one of the sentences, destruction of a few dozen gravesite memorials at a cemetery in Smolensk was qualified under Article 244 Part 2 Paragraphs “a” and “b” of the Criminal Code (“outrages upon Burial Places motivated by hooliganism and by ideological hatred”). For all four convicted offenders, the article related to property damage was not the only one and not the main one among their charges. The defendants were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment in conjunction with other Criminal Code articles – Article 35 Part 1, Article 116 (“battery by an organized group motivated by national hatred”), and Article 161 Part 2 Paragraph “d” (“robbery committed with the use of coercion”). This sentence was also reported in our “Prosecution for Violence” section.

Article 214 Part 2 of the Criminal Code (“vandalism, committed by reason of ideological hatred”) was the principal and the only article in the sentence issued in Yekaterinburg to Igor Shchuka, an activist of the Other Russia and a citizen of Belarus. The court sentenced him to a year of correctional labor for trying to set fire to the Boris Yeltsin monument.

In addition, we know of at least two more sentences delivered for apparent ideologically-motivated vandalism, in which the court sentence did not take the hate motive into account (both cases utilized Article 214 Part 1 of the Criminal Code).

Interestingly, a number of similar crimes (defilement of buildings and houses) have been qualified under Article 282 of the Criminal Code (“incitement of hatred”) for many years due to the dual nature of such offenses. The choice of an article to be applied is left to the discretion of law enforcement officers. Article 282 is probably better known by the media and, therefore, more popular among the law enforcement agencies.

[1] Our work in this area has been supported by the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, the International Partnership for Human Rights and the European Commission.

On December 30, 2016, SOVA Center was involuntarily included into the register of “non-profit organizations performing the functions of a foreign agent” by the Ministry of Justice. We disagree with this decision and have filed an appeal against it.

[2] Hate Crime Law: A Practical Guide. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR, 2009 (available on the OSCE website in several languages, including Russian: http://www.osce.org/odihr/36426).

Verkhovsky, Alexander. Criminal Law on Hate. Crime, Incitement to Hatred and Hate Speech in OSCE. Participating States. The Hague: 2016 (available on the SOVA Center website: http://www.sova-center.ru/files/books/osce-laws-eng-16.pdf).

[3] Data for 2017 and 2018 is cited as of January 8, 2019

[4] Our similar report for 2017, for example, reported 6 dead, 71 injured. See: Yudina, N., Xenophobia in Figures: Hate Crime in Russia and Efforts to Counteract It in 2017. 2018. 12 February, (https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2018/02/d38830).

[5] One person was killed in the preceding year as well.

[6] See: Kursk: A student from Nigeria was attacked // SOVA Center. 2018. 1 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/03/d38937/).

[7] New videos of the neo-Nazi “White Car” action appeared on the Internet // SOVA Center. 2018. 4 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/07/d39661/).

[8] Murder of a 9-year-old girl nearly triggered anti-Roma pogroms // SOVA Center. 2018. 7 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/08/d39822/).

[9] These attacks peaked in 2007 (7 killed, 118 wounded), and were in a constant decline since then, reaching a minimum in 2013 (7 wounded); the dynamics has been unstable since then.

[10] For more details see: Vera Alperovich, Natalia Yudina. Pro-Kremlin and Oppositional – with the Shield and on It// SOVA Center. 2015. August 31( https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2015/08/d32675/).

[11] The action was also attended by nationalists from the other side of political spectrum. For details, see the report: Alperovich Vera. Prolonged Decadence: The Movement of Russian Nationalists in the Spring and Fall of 2018.

[12] Nationalists at the Protest of May 5 // SOVA Center. 2018. 8 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/05/d39325/).

[13] St. Petersburg: Passer-by attacked activists because of the Ukrainian flag // SOVA Center. 2018. 21 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/08/d39869/0.

[14] In St. Petersburg, a passer-by attacked a solitary picketer // SOVA Center. 2018. 12 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/03/d38982/).

[15] Racism and xenophobia. Findings. April 2018 // SOVA Center. 2018. 29 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2018/04/d39295/).

[16] Attack on the Sakharov Center in Moscow // SOVA Center. 2018. 1 May (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/05/d39299/).

[17] St. Petersburg: Verdict was issued in Dina Garina’s case // SOVA Center. 2018. 19 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/12/d40438/).

[18] Actor Yevgeny Sapaev, who had underwent a sex reassignment surgery. See: Murder in Moscow // SOVA Center. 2018. 2 April (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/04/d39123/).

[19] Motivated by Hatred: Sociologists have recorded an increase in the number of attacks against LGBT in Russia // Takie Dela. 2017. 21 November (https://takiedela.ru/news/2017/11/21/po-motivam-nenavisti/).

[20] Two videos with scenes of neo-Nazi murders and beatings were found on the Internet // SOVA Center. 2018. 30 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/10/d40212/).

[21] Naive cruelty: why teenagers attack the homeless // Moskva 24. 2016. 24 January (https://www.m24.ru/articles/podrostki/14012016/94481).

[22] Chelyabinsk: Verdict issued in the case of the local Misanthropic Division cell // SOVA Center. 2018. 14 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/09/d40015/).

[23] Subway dispute about faith ended with a knife wound // SOVA Center. 2018. 17 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/religion/news/extremism/murders-violence/2018/09/d40024/).

[24] A young man beat up a young woman while yelling neo-Nazi slogans // SOVA Center. 2018. 1 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/09/d39945/).

[25] See Yudina, N., Xenophobia in Figures: Hate Crime in Russia and Efforts to Counteract It in 2017. 2018. 12 February, https://www.sova-center.ru/en/xenophobia/reports-analyses/2018/02/d38830).

[26] Discriminatory incidents in Russian football, 2017 – 2018 // FARE. 2018. May (http://farenet.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/FINAL-SOVA-monitoring-report_2018-6.pdf).

[27] Russian skinheads: A wild incident occurred at the 2018 World Cup // Obozrevatel. 2018. 16 June (https://www.obozrevatel.com/sport/football/russkie-skinhedyi-na-chm-2018-proizoshel-dikij-intsident.htm).

[28] The racist chants of Spartak fans directed at the Lokomotiv goalkeeper // SOVA Center. 2018. 2 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/12/d40364/).

[29] Vandals in Novokuznetsk take the Armenian alphabet for the Jewish one // SOVA Center. 2018. 26 February (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2018/02/d38916/).

[30] Only the sentences that we consider appropriate are included in this count.

[31] Murder of an antifascist musician in Moscow // SOVA Center. 2005. 14 November (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/racism-nationalism/2005/11/d6326/).

[32] St. Petersburg: an accomplice in the murder of Timur Kacharava was punished with 1.5 years in a penal colony // SOVA Center. 2018. 20 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/02/d38904/).

[33] Olga Tseitlina and Stefania Kulaeva comment on the Alexander Zenin case // SOVA Center. 2018ю 14 September (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/publications/2018/09/d40002/).

[34] This was a re-trial of the Martsinkevich’s criminal case. In June 2017, the Babushkinsky District Court sentenced him to the same prison term, having added a nine-year sentence in the case of the Restrukt! Movement to one unserved year in his previous sentence. Moscow: The verdict was delivered to Maxim Martsinkevich and his accomplices // SOVA Center. 2018 29 December (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2017/06/d37365/).

[35] Ali Yakupov was acquitted again // SOVA Center. 2017. 27 November (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2017/11/d38357/).

[36] Rock music fans as a social group // SOVA Center. 2011. 26 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/other-actions/2011/07/d22208/).

[37] The trial of the Yuri Budanov murder case has begun // SOVA Center. 2012. 16 November (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2012/11/d25822/).

[38] Rapper Ptakha was fined under Art. 282 // SOVA Center. 2017. 16 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2017/03/d36599/).

[39] A St. Petersburg court did not recognize materials on human rights violations in psychiatry as extremist // SOVA Center. 2018. 14 August (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/counteraction/2012/07/d24792/).

[40] Rozhana, the man-hater // SOVA Center. 2013. 23 October (https://www.sova-center.ru/misuse/news/persecution/2013/10/d28230/).

[41] Verdict delivered in Kazan in the case of an attack against the natives of Tajikistan // SOVA Center. 2011. 18 March (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2011/03/d21193/).

[42] Novosibirsk: Verdict delivered in the case of hooliganism with the motive of hatred toward the social group "anime" // SOVA Center. 2018. 2 July (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/07/d39640/).

[43] See for example: Verkhovsky, A., Kozhevnikova, Galina. Inappropriate Enforcement of Anti-Extremist Legislation in Russia in 2008 // SOVA Center. 2009. 21 April (http://www.sova-center.ru/en/misuse/reports-analyses/2009/04/d15800/).

[44] Kalmykia: a suspended sentence for beating and an attempt to set a vehicle on fire // SOVA Center. 2018 (https://www.sova-center.ru/racism-xenophobia/news/counteraction/2018/12/d40435/)